4,783 Total views, 1 Views today

By Fiona Crouch

I can’t imagine a world where I don’t have a voice; a world where I am powerless and live in fear. All women should be able to enjoy the life they want, choose their future and realise their full potential. Yet, in some parts of the world, women remain second class citizens; where women’s voting rights, education, and healthcare (including birth control) are still distant dreams.

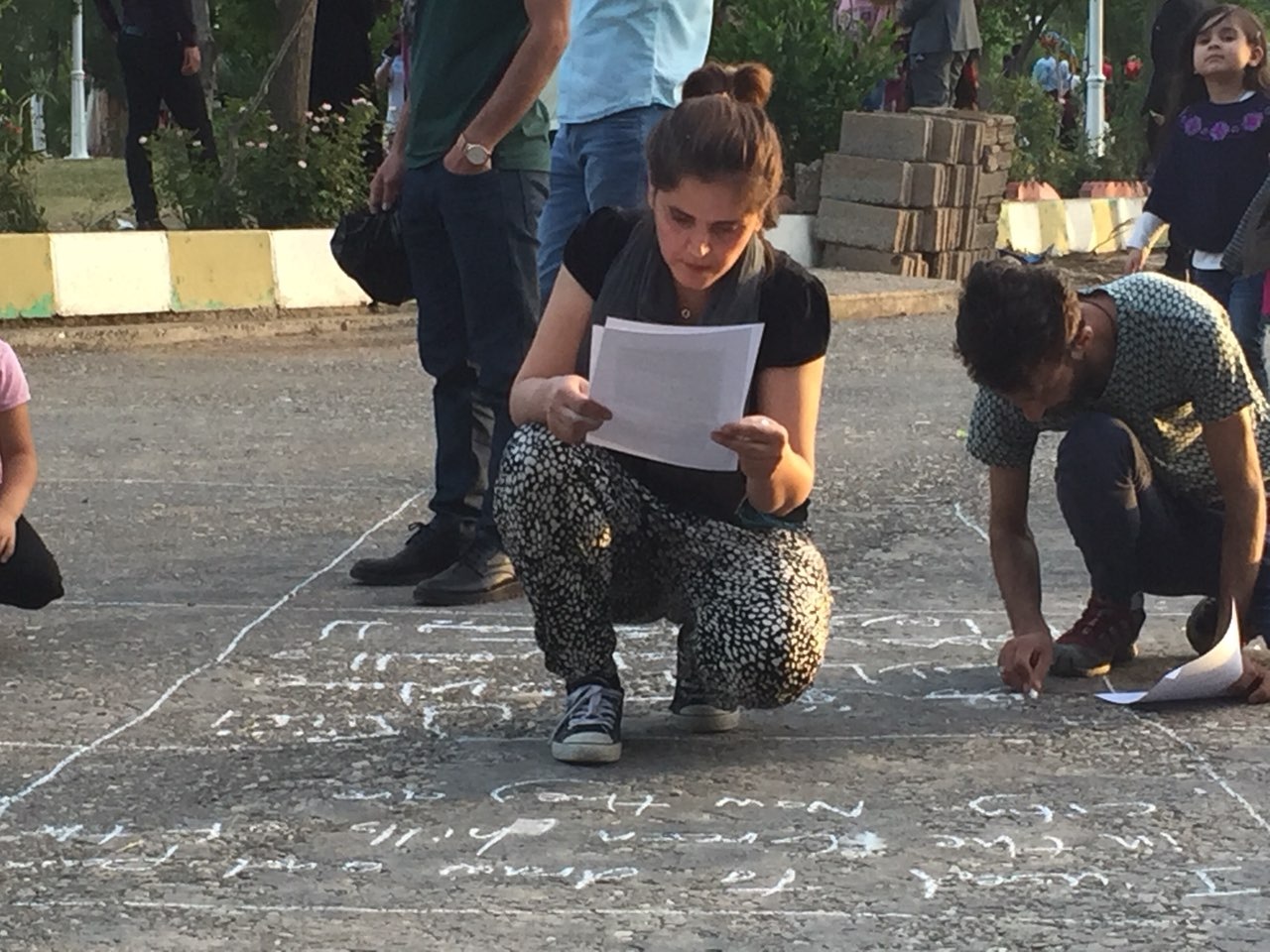

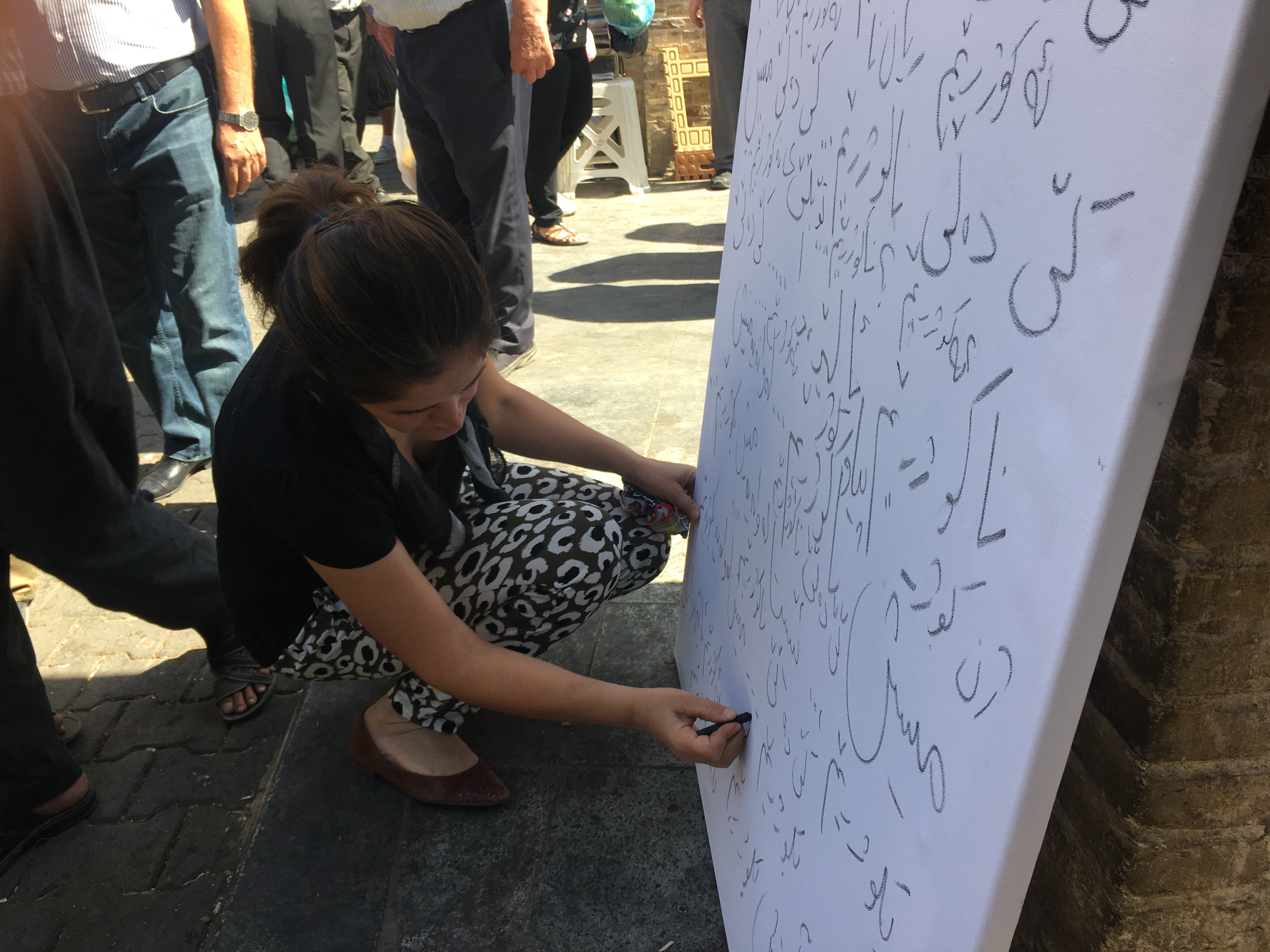

Art is a way of broaching these contentious topics to enable meaningful conversations. Rozhgar Mustafa’s work presents these uncomfortable realities to her viewers; daring us to consider difficult issues such as conflict, trauma, fear, gender identity, memory and contradiction. However, she does this in a way that offers a human perspective; a thread to pull at to ease into difficult topics. Her creativity challenges Iraqi Kurdistan’s inequalities, endeavouring to transform the status quo to bring about a fairer and more inclusive society. After completing postgraduate studies at Chelsea College of Art and Design in 2013, Rozhgar returned to Kurdistan with the aim of using her art to question the country’s existing conditions, to be a champion for those who have no voice. Rozhgar is multi-talented. She is trained in Fine Art but she often chooses to disseminate her message through different media including: installations, video, and public live action. By using different styles and media for her artwork, Rozhgar maximises the impact of her work, keeping it fresh and relevant to a range of audiences. This multifaceted approach adds layers of nuance to her pieces: they challenge traditional Kurdish audiences from both aesthetic and thematic perspectives. Rozhgar acknowledges that audiences need to see ‘the real physical works’ to be able to engage with and make meaning of the pieces – it is a relationship that needs to be face-to-face to flourish so that the audience ‘feel the works and have a journey with them’. She goads her audiences into engaging with the pieces and discussing concepts and messages that underpin each piece.

The use of the Shaab Teahouse to host screenings of her video pieces, ‘I Am Similar To My Father’ and ‘I Sacrifice Myself For You’, was an inspired choice. In Middle Eastern cultures, traditional teahouses are usually male-dominated spaces. They are places where men socialise and often discuss politics and the news, bastions of machismo and male solidarity. Patrons are unused to teahouses being used to question current societal conditions and, yet, this is the intent of these pieces. By taking her art to an audience that would be unlikely to talk about social inequalities, Rozhgar makes a bold and courageous statement, striking at Iraqi patriarchy on its home turf.

‘I Sacrifice Myself For You’ or ‘Baqwrbantm’ in Kurdish resonates on a number of levels. In this video, Rozhgar strips herself emotionally bare to the audience, revealing her anger at the killing of an anonymous woman in Iraq. She is featured alongside a Kurdish language newspaper whose headline announces the murder. A tea cup and spoon rest on top of the newspaper and, as the video progresses, Rozghar is featured stirring its contents, her fury clear. She repeats the word ‘baqwrbantm’ to reinforce her anger. By portraying the murder of an anonymous woman, does this make the piece more or less powerful? For me, it increases the potency of the film: the unnamed female comes to stand for every woman, in the same way that Margaret Atwood’s handmaids symbolise most women in the fictional Gilead. There is a sense of menace and the threat of male dominance throughout the piece.

The exploration of male power is visible throughout much of Rozhgar’s work. In the ongoing aftermath of the #MeToo movement, this remains very relevant. It prompts in my mind the controversy surrounding Noel Clarke, a man who is alleged to have used his status to bully and engage in sexually inappropriate behaviour with women he worked with or employed. In the Kurdistan region and across Iraq as a whole, honour killings and violence, often at the hands of family members, are the tragic lived experience for many women. I feel strongly that it is beholden on humankind to stand up for those who need our support. The willingness of the tearoom owners to screen Mustafa’s performance art pieces that are noisy and politically-charged is courageous – a metaphorical stand for equality of both genders in Kurdish society. What was the response of the predominantly male audiences to this cinematic invasion? After some initial shock, the regulars were interested in the piece, curious to explore Rozhgar’s intent. This vindicates her assertion that art can affect change. I am reminded of the classical Roman quote (usually attributed to Ovid) that ‘dripping water hollows out stone, not through force but through persistence’. If an artist is able to take their audience with them, it becomes their voyage of self-realisation too: the water has changed the stone.

Rozhgar displays similar vision and fortitude in ‘Five Plastic Women Protestors’. She arranged for a group of male protestors to carry five plastic mannequins at a rally to protest against the Kurdistan Regional Government in Sulaymaniya’s Sara Square in 2011. Rozhgar directed this piece from a distance, using men to portray a message of gender equality. This piece of performance art enabled Kurdish women to exert their right to protest in absentia, in a milieu where it was not physically safe for them to do so. There is a strong sense of irony that silent mannequins have given Kurdish women a voice. What does it mean that the Plastic Women Protestors are being carried by men? Do you interpret this as supportive or indicative of the fact that, without men, women have no power in their own right?

Rozhgar displays similar vision and fortitude in ‘Five Plastic Women Protestors’. She arranged for a group of male protestors to carry five plastic mannequins at a rally to protest against the Kurdistan Regional Government in Sulaymaniya’s Sara Square in 2011. Rozhgar directed this piece from a distance, using men to portray a message of gender equality. This piece of performance art enabled Kurdish women to exert their right to protest in absentia, in a milieu where it was not physically safe for them to do so. There is a strong sense of irony that silent mannequins have given Kurdish women a voice. What does it mean that the Plastic Women Protestors are being carried by men? Do you interpret this as supportive or indicative of the fact that, without men, women have no power in their own right?

So, at a fundamental level, what do you believe is the purpose of art? Is it merely to be critically admired, its beauty praised? I think it’s an expression of humanity, a way to explore identity as individuals and groups so that it prompts discussion: it introduces tension that can catalyse change. In my mind’s eye, sometime soon, I am seated at a table in the Shaab Teahouse. I am surrounded by the thrum of voices, the chink of crockery and the tap of domino tiles hitting the table tops. I catch the eye of a large group of women at the table next to me; we smile. Rozghar’s art has succeeded, it has brought about change. I feel this is a version of everyday life that Rozhgar would be proud to have inspired.