3,471 Total views, 3 Views today

Shajwan Fatah

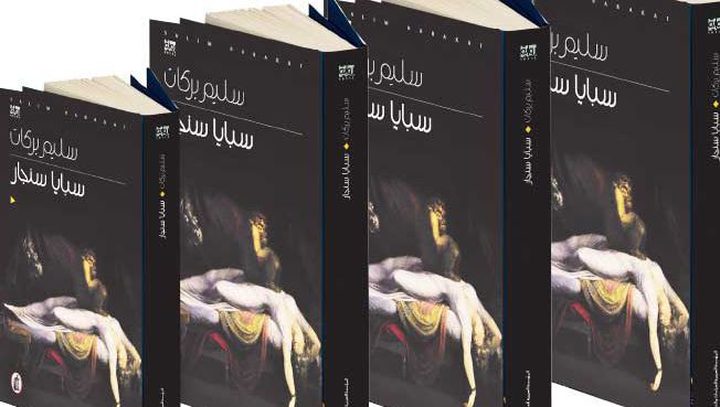

Salim Barakat’s Sapaya Sinjar or The Captives of Sinjar was published in 2016. Besides Henry Fuseli’s artwork “The Nightmare,” the title composition – “The Captives of Sinjar” – seizes readers’ eyes from the first sight of the book cover. These terms summarize a conceptual framework wherein a collective of captives or hostages is figuratively encapsulated within the spatial confines of – Sinjar – a habitation nestled within the precincts of the Nineveh Governorate in the northern expanse of Iraq, strategically situated at an approximate distance of five kilometers southwards from the Sinjar Mountains. The hermeneutical essence of the text appears to unveil itself seamlessly from the very guise of its title features. In other words, the novel is based on the narratives of the actual events that happened in Sinjar back in 2014.

Here I would shed light on the biographical context the author– Salim Barakat – a novelist, and poet from a Kurdish-Syrian background, was born in 1951 in Qamishli, located in the northeastern part of Syria. After a year of studying the Arabic language in Damascus, he moved to Beirut in 1972. During his time there, he released five volumes of poetry, two novels, and two autobiographical works. In 1982, he changed his base to Cyprus, taking up an editorial role at the renowned Palestinian literary magazine Al-Carmel, where he served under the leadership of Mahmoud Darwish. During this period, he authored an additional seven novels and five collections of poetry. In 1999, Barakat made a move to Sweden, where he currently resides. His literary creations delve into various facets of the cultures present in Syria, encompassing Arab, Kurdish, Assyrian, and Armenian influences.

In order to understand Barakat’s work, it is essential to give a brief historical background of incidents that happened in Sinjar during its dark age which goes back to the summer months of 2014, back when the Yezidi and Christian communities of Nineveh and Shingal (Sinjar), along with various other civilians representing diverse religious and ethnic groups in Iraq, faced a dire situation when the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) launched an offensive in the region. Faced with the imminent threats of death, enslavement, and coerced conversion, a substantial number of people were compelled to abandon their homes. Tragically, it is estimated that within a short span of time, nearly 10,000 Yezidis lost their lives, and thousands of women and girls were abducted and subjected to enslavement.[1] The severity of the violence extended across the area, spanning from the major city of Mosul to the smaller Yezidi villages around Shingal, where ISIS explicitly displayed its genocidal intent.

A report published in September 2015 by the Simon-Skjodt, Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, meticulously outlines the systematic killing and abduction carried out by ISIS against the Yezidi population of Shingal, ultimately concluding that these actions constituted genocide. The report also highlights that the persecution of Assyrian Christians, Sabaean-Mandaeans, Shabak Muslims, Turkmen, and Kaka’i by the Islamic State falls within the categories of religious and ethnic cleansing. Notably, the United States, the United Nations Human Rights Council, and various other governments and international organizations have all recognized that the crimes committed by ISIS met the legal criteria for genocide in 2016. These tragic events and their aftermath, which resulted in a significant refugee crisis, have left a profound impact on the Kurdistan Region. By the close of 2014, the United Nations reported that Kurdistan had provided shelter for over a million refugees and internally displaced individuals (IDPs). As of now, this number has increased to nearly two million. As more areas are liberated from ISIS control, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) remains dedicated to supporting survivors, documenting the atrocities committed by ISIS, and offering assistance to the many who are still held captive.

One could say that commonly, in scholarly discourse, the occurrences of the Yazidi genocide have conventionally been interpreted within the contexts of ethnicity, religiosity, and political dynamics. However, Barakat traverses a more profound intellectual trajectory, engendering a contemplative space for an exploration into the intricacies of human nature. Within his work, he extends an invitation to readers to contemplate both the intrinsic and extrinsic conflicts that pervade the human condition. The narrative, emanating from the rich fabric of this work, effectively unveils an alternate perspective of the Yazidi genocide – one that transcends the mere horror and desolation to engage with philosophical and artistic paradigms.

Upon the commencement of the reader’s engagement with the inaugural passages of the narrative, an aesthetic paradigm ensues, steeped in the ethos of Surrealism,[2] which seems to operate as the philosophical side of the text. That is to say, the actual events are presented in an artistic way that implicitly analyzes the historical incidents, and metaphorically, they show the human state of nature. This is also marked by its characteristic interplay of dream-like sequences and perceptual vagaries. the male narrative voice – Sarat –is a Kurdish-Syrian painter who lives in Sweden, and takes the audience to absurd scenes shifting back and forth between his surroundings in Sweden and the imagined places in Sinjar; different corners are depicted in the work. In addition to this, the narrative perspective immerses us within the confines of artworks primarily originating from the 15th to 18th centuries, the periods characterized by the Renaissance and then the Enlightenment when humanity’s foundational principles began to undergo critical scrutiny. This literary device employed by Barakat seemingly prompts readers to engage in a discourse that challenges the orchestrated ideologies fostering acts of violence and bias within these entities. That is to say, we, as readers travel through history into various different situations which all highlight the dark side of humans in the state of nature. Surpassing reality, Sarat meets the spirits of several characters who are classified into two groups: a minor group who are the female captives – oppressed – and the major ones, on the other hand, male figures – the ISIS fighters, who are obviously, the oppressors. Throughout the ten chapters; Sarat sees and explains various artworks that are based on depicting horror and violence through the close reading of their subject matter, color, and elements, which has the analogy of the same darkness of the captives and captors.

The novel’s temporal framework initiates at daybreak and concludes at nightfall, metaphorically alluding to the span of a lifetime back then in Sinjar. Sarat’s opening discourse on Henry Fuseli’s work “The Nightmare” seems to carry symbolic weight, signifying the overarching narrative. Additionally, amidst the unfolding events, historical, philosophical, and political dimensions are interjected into the discourse. In Chapter Two, Sarat introduces us to the traditions and the cultural background of Yazidis through the representations of William Blake’s “The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea”. This appears to assert the idea of the subject reality relating to a certain ethnic group that has its own origins as any other nation. Strikingly, the spirit of female characters whom Sarat meets are aged from eleven to seventeen years old, and are oppressed by a manufactured patriarchal ideology of male characters, these female figures are eventually murdered in brutal ways. As we turn the pages, we meet Shahika, Nenas, Anesha, Kedema, and Yada, all in covered bodies; wearing burqa, and standing there with silence on their young faces. Apart from the traditional reading of these evocations, I would like to unravel the significations that lead us to the idea of gender issues that are disguised by fabricated beliefs against women throughout history. If we ask a rational question the reason why women are the ones who are supposed to be the oppressed within the political, social, and religious conflicts? And why do they constantly play the role of subalterns? Remarkably, Barakat depicts various hidden aspects, not only political and racial confrontations but also, the constructed doctrine of a population who are not aware of the concrete reality. This is how Sarat compares the horrifying details recounted bear a striking resemblance to the imagery depicted in Titian’s “Punishment of Marsyas”, one of the scenes that is completely depicted in this painting is how little children – boys – have been trained by ISIS fighters to slaughter others, and also to play with beheaded heads in Barakat’s chapter Three. In the latter chapters, the author sheds light on the human state of nature – that is to say, he reveals hatred, jealousy, sexuality, greed, and hypocrisy through Sarat’s conversation with the imaginary male characters – ISIS fighters –their narratives are based on how they have murdered each other’s because of the dark side within their human state of nature, thus, the speaker goes back through history and shows us a collection of famous artworks such as “Death of Marat” by Edvard Munch, “The Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymus Bosch, and “Judith Beheading Holofernes” by Caravaggio. I would call these chapters the other side of human history, surpassing politics and religion – Understanding the human essence from both within and without. To what extent do readers see their subjective realities not from their ethnic or religious background, but from the very beginning or their primitive beings? And this is the essence of Barakat’s novel. It is also essential to state: apart from the female characters, readers meet the other group – ISIS fighters – such as Adnan, Ali, Ihsan, Abdullah, and others, who are entangled with the beliefs of murder and enslaving women so that they establish an Islamic state and win the other life – Jannah – as they are fascinated with depicting their images in Sarat’s paintings in the way they see themselves with absolute power.

Once again, we – as modern readers – could read this text through various lenses. I would say, the novel seems to disregard the conventional way of reading history, but actually, it instructs the audience on immense layers of philosophical aspects. From shallow layers, one could narrate what happened in Sinjar, but rarely, scholars would ask why. And how? If we study the philosophy of politics, once again, we may need to question, what is politics. And how does political propaganda operate? Barakat seems to answer these questions through his surrealist style. Towards the end of the novel, Sarat concludes his narrative – the nightmare – by looking at Theodore Gericault’s “The Raft of the Medusa” as he is summoned by the female characters to join them by the sea. I want to assert that Gericault’s artwork serves as a metaphor for the Yazidi survivors who managed to escape the nightmarish confines of ISIS’ rule and regime. Additionally, in the last pages, the protagonist mentions artistic works from both Turkish and Iranian origins within his Kurdish-Syrian home, underscoring the intricate political landscape of the era. From a national lens, this also reminds us of the famous Kurdish expression “no friends, but the mountains,” and this is how Barakat gives the beauty of the mountains of Sinjar over the darkness of the sea.

References

Barakat, S. (2016). The Captives of Sinjar. Arabic [Sabaya Sinjar]. Beirut: al-Muassassah al-ʿArabiyyah lil-Dirāsat wa al-Nashr.

ISIS genocide of Yezidis and Christians. (n.d.). Retrieved from Kurdistan Regional Government: Representation in the United States: https://us.gov.krd/en/issues/isis-genocide-of-yezidis-and-christians/

Salim Barakat. (n.d.). Retrieved from International Prize for Arabic Fiction: https://www.arabicfiction.org/en/node/1556

[1]Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States. https://us.gov.krd/en/issues/isis-genocide-of-yezidis-and-christians/

[2] Surrealism emerged as an artistic and literary movement in Europe during the period between World Wars I and II. This movement served as a response to what its members perceived as the devastating impact of “rationalism” on European culture and politics, particularly in the aftermath of World War I, when it had resulted in widespread destruction. Britannica.com https://www.britannica.com/art/Surrealism