2,521 Total views, 2 Views today

Between Moving Spots

Ismail Amin Hamalaw

1

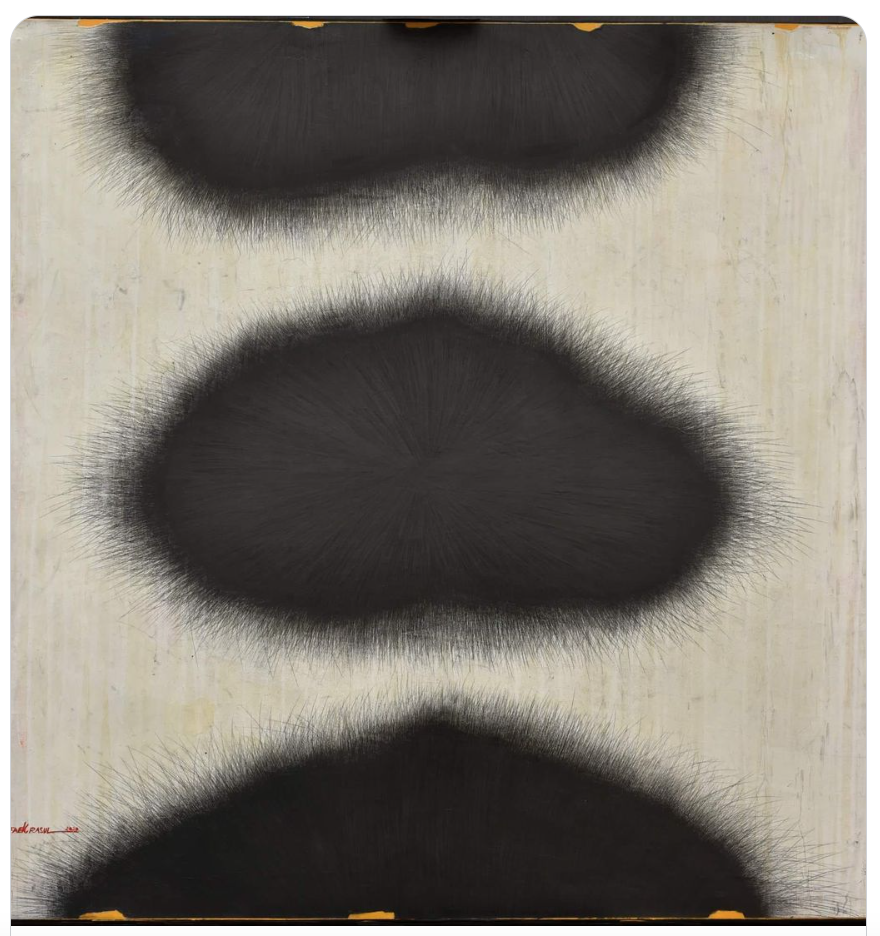

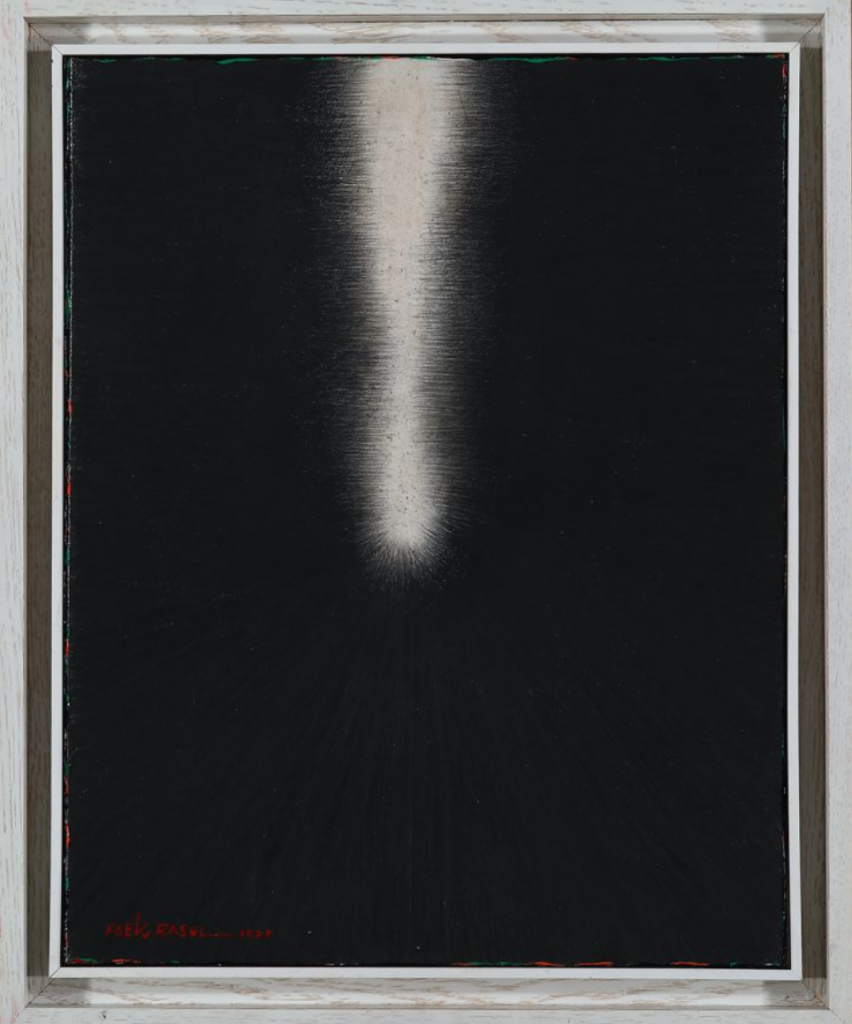

When the “geometric black spots” begin to move, they emerge from a deep memory, out of which their different shapes are formed and so become visible. At this moment they also develop into a part of the artist’s subject and play a significant role in locating the shapes in the mirror of historical occurrences.

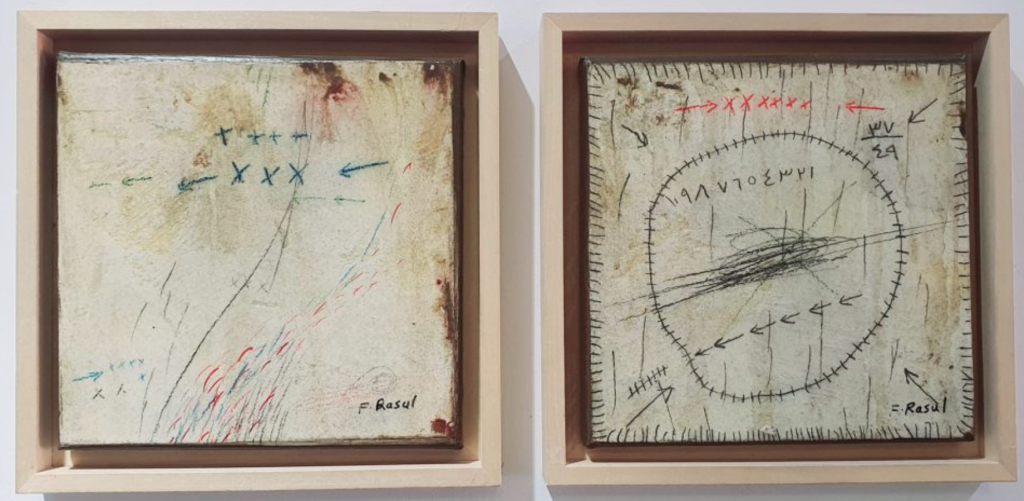

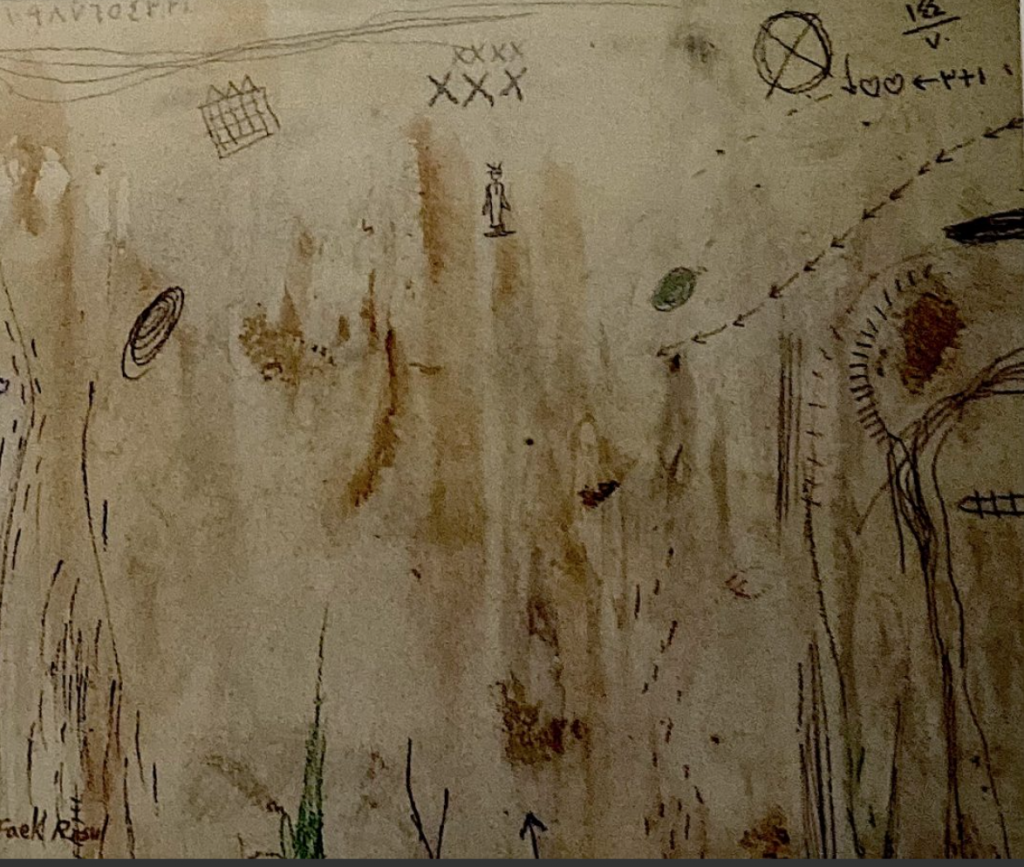

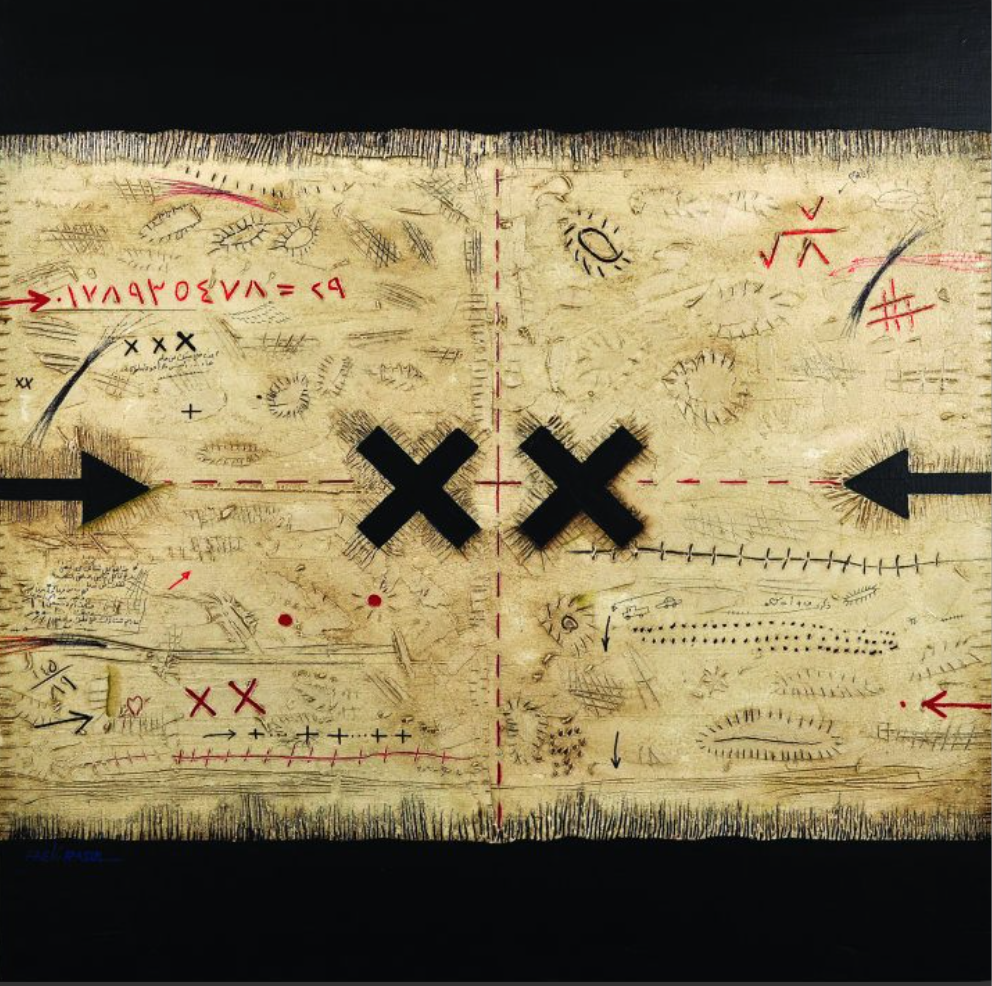

I gained these impressions when I came across a series of works by the painter Faek Rasul. The paintings were exhibited in the Vienna studio between 2017 and 2023, creations using various mixed techniques. This is a series of paintings entitled “Memories”, in which the arrangement and apparent movement of geometric dots gives the feeling of diving into another world through the lens of a microscope. It’s like looking through a microscope while being detached from the world around and perceiving specks, black lines, dashes, and black streaks amidst a black and gray world. A presence permeates the concepts and imagery of these paintings, while history quietly casts gray shadows on the forms, expressing historical violence through a “geography of silence”.

These spots look like they traverse the surface or background of a muddy body of water and leave trails, you can also see how the light reflects in the murky water. Here and there, red, dark yellow, dark green and blue dots float and maneuver on the surface like microscopic organisms. If you take a step back from the paintings and look at them more closely from there, you can feel how light penetrates your eyes and the sun casts its glow on your eyelids. Thus, microscopic creatures become visible amidst black and gray blotches on a muddy white background in various patterns that also resemble stray water droplets on the fading stained remnants of paint in a gutter.

The artworks are rendered in various sizes and mixed media, with the artist Faek Rasul employing a range of tools from coloured pencils to pastels and incorporating the use of oil paint on the surfaces. The entire painting series serves as an interface for the viewer’s imagination. There is no imposition, no pressure stemming from a dominant idea, and no imposition of any particular meaning upon the viewer. These artworks, in essence, provide an interface for unencumbered thought, contemplation, imagination, and the evasion of conventional interpretations.

In certain paintings, the details and core meanings appear enhanced by different shapes and a light background. Within these, light infiltrates akin to a liberated imagination via a thin raw material splattered with rests of droplets, rain, or waterdrops. These extend into tight, serpentine recesses, culminating in black and grey patches. All of these signify motions among spots, their remnants on the surface of the paintings evoking a sense that something has transpired here; an occurrence has transited this space, a tremor from the depths of memory revealing hues and outlines on the paintings’ surface.

Here we stand now confronted with the last fingerprints, traces and remains of an event. They all awaken in the soul a sense of historicity, loss, violence and severity of heart. The violent movement of the black spots with their gray edges through muddy water full of microscopic creatures gives us the impression that an “event” has taken place here.

On the other hand, a constant presence is embodied through the stains and even through the mathematical signs applied to the surfaces. Here, however, it is through a series of brightly colored tableaus in which the light turns to dark yellow and green. These works are the same mixed technique, but on a dark green and yellow surface and with various symbols and equations that seem to be painted on a wall. Numbers like 144/70 or someone’s name “Farooq Omar” written in small letters. Or you can see a sinuous line, as if someone wanted to draw a snake on a wall. A colorful circle painted in different colors from top to bottom. It seems as if the world of paintings is telling you, “Many people have passed by this wall and immortalized themselves with these signs.” All of this takes us back to the world of microspheres, where all the small things begin. The world of small things we experienced in the works of art between black and white and different dots.

There is also another series of paintings in which black spots and gray shapes are not so obviously perceptible. But unlike the previous series of works, these have a differentiated light surface. The artworks have a dark green background mixed with yellow and rust-colored lines. In some places there are even black spots and various lines. All this brings another movement, a slowing down of black and gray on a light surface, where dark green and yellow become the background of mythical symbols.

These series of paintings thus lead us through several gateways, allowing us to expand our own observations between the movements of the spots. From memories to scars to mythological symbols, they provide us a window through which scars and meanings of peace, violence, historicity, and distant memory are transported. Simultaneously, they convey four artistic interpretations of these works of art: the first is the presence of black and grey, the second is the disappearance of the figure, the third is the world of small things or microspheres, and the fourth is the resurgence of the figure through artistic sensation, naturally after undergoing deformation.

2

When I am confronted with this series of artworks, the question arises: why return to black spots? Why start with black and then leave the warm colors (Memories 1980 – 2006)[1] to once again start with the color black? In what new form do black and gray appear in Faek Rasul?

Black was often not regarded as a colour, but rather as the “absence of light,” because where there is black, darkness has swallowed the light. Where black is present, it has restrained other colours, bestowed balance upon them, and restored equilibrium among different colours. No wonder Henry Matisse said in 1946, “Whenever I used black, I had doubts about which colour I should use, for black is power.” [2]

As a Fauvist, as an avant-garde artist, Henri Matisse placed colour ahead of the realistic world in the realm of painting. For the Fauvists, colours are their own representatives, not representatives of specific realistic figures or ideas. Thus, black presents itself as a force that balances the world while simultaneously obscuring light in a symbolic sense.

We must not forget that “Henri Matisse,” as an avant-garde figure, lived through two wars: World War I and World War II. In my opinion, this experience allowed “Matisse” to comprehend the authoritative version of war, and as a result, the power of black is not just the power of colour, but it also carries a cultural, historical, and psychological dimension.

I believe that in war, there are always two colours present: red and black. However, when red fades, psychologically, only black continues the tragedy of red. Therefore, the interplay between the power of black over red and other colours lies in the fact that the memory of red, the tragedy of red, persists after the red has faded into black. Just as black, in its tragic version, swallows all other colours, it carries the essence and memory of other colours within itself.

What we encounter culturally and psychologically in wars, revolutions and uprisings, is red, red as a warm color, a color that leaves its mark everywhere: in the trenches, the pits of the battlefield, the destroyed vehicles, the tanks and armored vehicles, the burned windows and frames, the streets full of corpses and rubble, the bloody and collapsed walls, and so on. Especially many of the walls are turned into paintings depicting the war, killing and torture. The walls are the only remnants of red: bloodstains, pieces of human flesh, remnants of black gunpowder and burns, and much more, what remains when bodies are destroyed becomes visible on the surface of the walls.

Naturally, in wars and battles, walls are “uninvolved” and apathetic, innocent, merely facades bearing witness to tragedy. But the wall is also the surface of innocent children’s drawings or representations of past bliss and memories. The walls are the sole witnesses, and they tell us: blood was shed here, people were killed here, bloodstains exist here, people harbored hopes, drew pictures, wrote mathematical equations, and enhanced themselves.

In a state of war, walls become another stage, a theatre of two dominant colours: black and red. In this sense, red and black consistently emerge to the surface in tragedies, showcasing war and bloodshed. But when the red fades or the war is over, only the gray rubble remains. Black and the subsequent fading into grey constitute the continuation of shattered bodies that death has left through memory. In this way of thinking, black and shades of grey take on an additional presence through colours, serving as nothing more than a continuation of tragedy and dreams. At this juncture the theme and object of “wall” widens into an enormous tragic and human space in Faek Rasul’s work, both through the writings on the wall, through the drawings that people have left on the walls, and through the spread of paint stains that reach back into the distant past.

However, in both these works and in the works from 1988, the artist resorts to using black and gray to comprehend the Kurdish tragedy of the genocide in 1988, named ‘Anfal,’ as well as torture, estrangement, forced migration, and so forth. This contrasts with the red color of revolution, war, and killing, and also with the white background. Therefore, we approach a ‘zero point of history.’

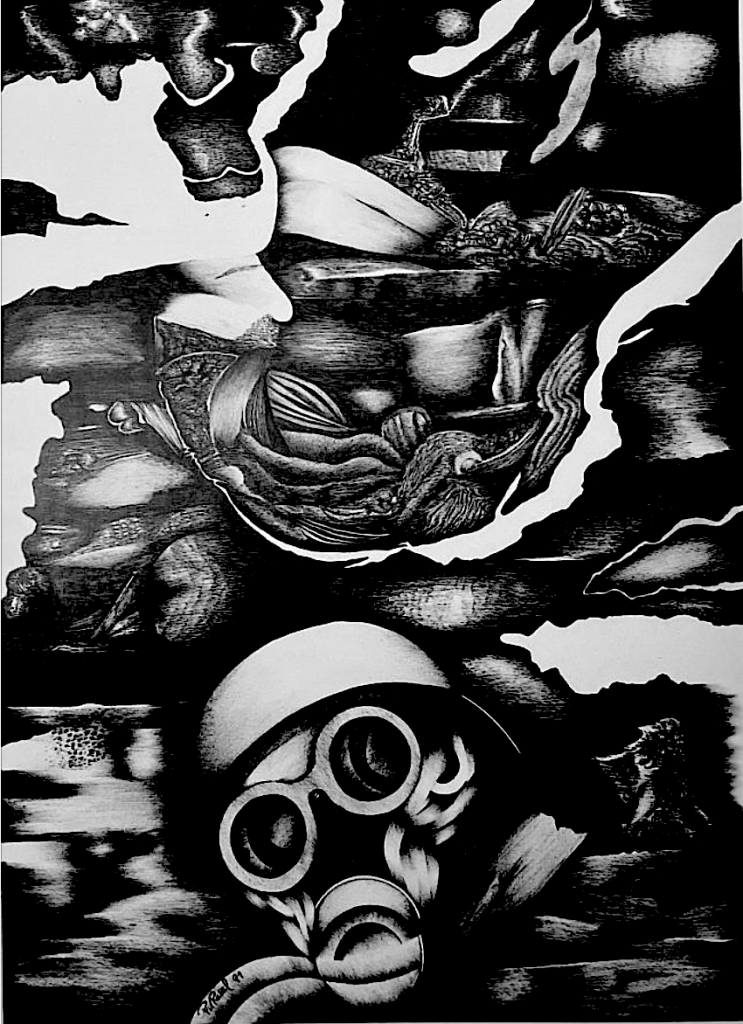

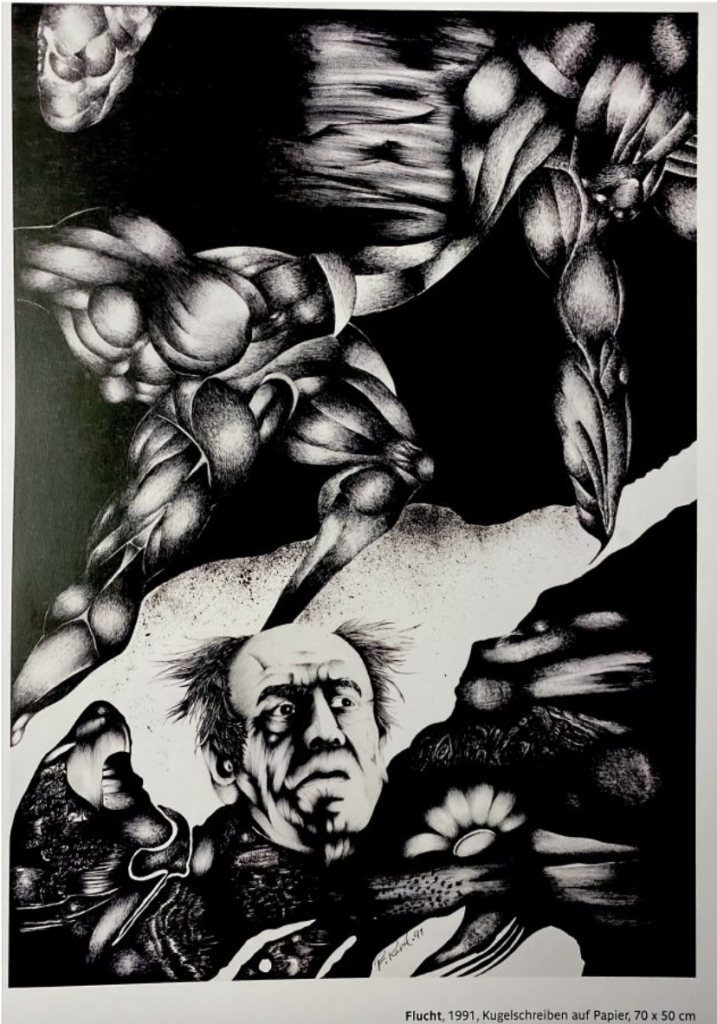

At this ‘zero point of history’, the color black has in the work of Faek Rasul, in the words of Henri Matisse, “an authoritarian presence”, especially in the catalogue ‘Memories – Images of 1980-2006’ and in the drawings of 1988 and 1999. In them we see six pencil drawings, including ‘Escape 1991’ and ‘Waiting for Godot (1991)’ and four drawings on paper. Their history goes back to 1988, when the Kurds were victims of chemical warfare, and eight genocidal attacks known as ‘Anfal’. In 1988, the regime of the dictator Saddam Hussein terrorized the Kurdish areas under the name of ‘Anfal Military Operation’, and more than 180,000 women, children and elderly people were victimized. They were imprisoned and systematically murdered in camps according to the Auschwitz model, in the southern Iraqi desert near the Iraqi-Saudi border.

Therefore, Faek Rasul’s artworks include masks, distorted bodies and faces of people whose bodies have been torn up and skinned by chemical bombs. All this becomes visible and tangible in his works. Skinning can be seen in the screaming faces of his drawings, faces made only of muscles and flesh but without skin.

Another painting (Dream1, 1988) shows two faces made only of muscles. Two faceless heads staring silently side by side, a look that has not been spared to reflect all the coldness and hatred of the world. Or in another painting (Dream 2, 1989) we see the torsos of two women without skulls, the body of one woman horizontal and the other like in a weaved line, their legs tied with a rope. Black and gray on a white background, still harbor the red of the remains of spilled blood and a terrible tragedy created by genocide, death, violence and silence.

3

This series of paintings allows us, as Peter Sloterdijk puts it, to enter the realm of “thinking gray“, but also to enter the gray zone, to linger there to then contemplate the black spots and stripes of Faek Rasul as they float in the dividing lines or spaces in between. We stand before a series of paintings in which things have lost their rigidity and stability. Everything goes to “zero” and looks for another breeding ground to reform and be reborn. Thus, in the gray zone, nothing stays the same; without cell bodies, without spheres, but even forms do not retain any of their original shapes. All enter into the deformation. They become part of the progressive deformation and decomposition.

The forms can be black spots or simple grey stripes running from top to bottom. Or they can be multiple circular spots emerging from the depths of the paintings, occupying the entire white space. On the other hand, we see spots resembling tiny, microscopic organisms like amoebas, their grey fibres running over light green and yellow surfaces. No matter where you look, grey leads back to black. No matter where you gaze, black leads back to its shadows, which are grey.

The question that concerns me is: why this deformation, this decomposition? Where does this concept of black and gray come from, considering that Faek Rasul had abandoned the black and gray palette of the 1980s in favor of the mythology of warm colors? In what context of the color palette do the design and presence of the forms relate to the essence of the artist?

I therefore believe that the concept of “Coming into the black” replaces “Coming into the world”. Or to put it another way, when art fills the world with color, listens to the “echoes of being,” and existential thinking takes us into the gray area where white, as the color of God, fades, black spots emerge in the gray area.[3]

This color thinking presents us with a different understanding of the world of form and deformation. When white enters the gray zone, it is crisscrossed by black spots. There, in the context of the Kurdish genocide “Anfal”, “God” loses all meaning as a unity of spiritual and material world and thus its white color. Then, in the course of the black spots and gray zones, the hustle and bustle of amoebas and microscopic creatures leads to the deformation of the divine; where a gray zone exists; the idea of the “zero point of history” finds its place.

The “zero point of history” is the moment when history loses its own historicity, like in a forward fall.[4] At this moment, the hiatus, the gaps and the openings announce the zero point of history. These interruptions and gaps engulf old forms, norms and ideals of history. From this perspective, generations search for a new era. And the confused descendants look for another way of life in the zero point of history, and art also strives for new forms and a new concept.

At the zero point of history, chauvinism, fascism and racism are entering the world. All ideals are shattered. The world is divided into two periods: before the war and after the war. Not only solid bodies, but also being and essence are threatened by destruction, decay and deformation. Above all, spaces are destroyed: the social ground that connects the self with the other; and the cultural space that aligns human norms, ideas and traditions. The architecture, the buildings, the houses and the “being at home” are destroyed, all forms are annihilated and the entire environment with all its living beings is subjected to the duality of life and death.

Wars devour every hiatus, every opening and great abyss, everything that once was in this world. Now gaps and various things, such as the discourse of fascism and death, emerge. Hiding places, dreams of imprisonment, prison cells and torture rooms, battlefields and pits full of bodies become the psychological and social topography of everyday life.

In the midst of this annihilation of history, in this fall into war and destruction, no lines and solid forms, no objects, no angles, no geometric and architectural arcs stay the same – everything faces a new negation, whether physical or material. It all breaks or dissolves; there will be no immunity and no prevention. What remain are the fragmentation, deformation and explosion of bodies, shattered and demolished walls, streets and caves.

In this contemplation we look at the surfaces and the black and gray spots of Faek Rasul’s paintings. The movement and the swimming of the black spots, the gray shapes and the expansion of the black on the white surface create a sphere as if after a bursting apart of coherent bubbles. The subject itself no longer comes to rest, because at a point where history catches up with it, the gaps and fractures become larger and more frightening. One self and the others no longer fit into the same social and psychological bubbles. Prevention and immunity disappear as the peaceful bubbles dissolve and migrate to another region. Each of these material and biological forms loses its previous form and floats through the spaces in search of a different geography and topography. They behave like the black and gray stains on the paintings that begin their odyssey out of memory and loss.

Anyone who looks at this series of paintings by Faek Rasul and compares it with the artist’s experiences in the 1980s, when he saw his own body and the bodies of others exposed to modern torture methods in the prisons of the Baathists, also approaches the stains expressed in this series of paintings. In order to gain an understandable view, we consider the particular approach to the deformations of the bodies that received their condition through inhuman contemporary technologies such as chemical warfare, atomic bombs, modern weapons and new methods of torture. Thus, for the Kurds, the 20th century was the century of deformed bodies. The 20th century was a century in which we were thrown into the inferno and the abyss of fascism and terrible war. At this point, and precisely in this series of paintings, the importance of the concept of this disfigurement of forms to geometric and amoebic stains, becomes clear; from then on, the stain itself is a liquid body that decomposes between the surface planes.

Faek Rasul’s childhood memories are associated with the bodies that were hung on light poles, left to swell, decay and decompose. Or the whole person was dissolved in acid or, like many others, exposed to chemical bombs. But also stones, rubble and pits or remains in murky waters are linked to childhood impressions. Let us not forget March 1980, when thousands of children, women and elderly were exposed to the poison gas attack by the Iraqi Air Force in Halabja. Their bodies swelled and then remained in their homes where they were left to decompose.

Thus the black spots, like body remains, seek a quiet place and the gaze follows the spots on their odyssey through the sewage. We see the movements, deformations and remnants of colors and geometric objects in the microscopic realm, a “microsphere” of memories that, however, now drop into white, green and sugary surfaces.

4

In the center of this chaos at the zero point of history, art becomes the answer. While art may still focus on past ideals and the established powers lose their value in the discourse of the old artistic idealists and, like many ideals, stand on the brink of decline, art can from now on find new ways again.

If we include this perspective in our artistic thoughts, art becomes a fresh offspring in search of another life. After the war, after the hiatus, the reorientation leads again to a generation searching for better concepts of life. Art by finding a different way of looking at itself becomes a reaction to this zero point of history, which also exists on an individual level.

That is why we face these domains; I have always believed in the creation of spheres. Therefore, generating small spaces, new bubbles, new cell bodies and even new souls becomes important to reconcile new ideas and concepts; the generating of new immunities that a new generation needs after catastrophes, after a zero point in history. Here art becomes a reaction to the recreation of spheres, because within the spheres, in new areas, you find another space, a place similar to life in bubbles, where two poles share life.[5]

The question to this thesis: What happens when the bubble bursts and there is no more self-protection or immunity and the spirit of a sphere loses its density and solidity, turns into foams, dissolves and disperses? Then follows the search for a new harmonization; where the bubbles explode, the foams remain. And where we lose form, we gain change. Thus, progressive change in Faek Rasul’s paintings becomes a reaction to the loss of form and figure, a search for new design.

5

If we consider the zero point of history in this historical context, we have to ask ourselves: Where do the spots in this series of paintings come from? Or rather, where were they before? The answer, of course, lies in the spiritual realm and in the history of the Kurdish spirit. This history is reflected in the paintings and represents the life experience of the artist Faek Rasul. If we take a look at the artist’s biography, but also look back at his experiences from then in 1963, we see that it was always difficult for him to talk about it.[6] Therefore, Faek Rasul clearly expressed himself through his painting.

One such experience took place in 1963, when his family was forcibly relocated from their village of Shoraw to the Kurdish city of Kirkuk because of their Kurdish identity. This forced relocation dates back to the Baathist and Arab nationalist taking power in 1963, through a coup d’état against the government of General Abdul Karim Qasim. Both the Arab nationalists, led by Iraqi President Abdul Salam Arif, and the Baathists, led by General Ahmad Hassan Bakr and Saddam Hussein, pursued the idea of dissolving the Kurdish identity and expelling and annihilating the Kurds. Therefore, after their successful coup in 1963, they established a special force, the National Guard. Their first task was to expel and suppress the Kurds in cities such as Kirkuk, Sulaimaniyya, Erbil and all cities officially known as Kurdish areas in northern Iraq, even shooting and killing them publicly.[7]

After this terrible period in Kurdish history in 1963, Faek Rasul experienced as a child two types of “object deformation” and distortion of figures and bodies

First: the houses in Shoraw are demolished and turned into concrete rubble. Thus, in the childish memory of Faek Rasul, the color gray symbolizes the first encounter with an “object deformation “, likewise, the poor storage of the books of his father’s private library in plastic bags to protect them from possible inspections by the National Guard. These books then change shape; some tear, while others develop damp stains and streaks on the pages. These moisture stains manifest as brown lines, root-like structures, and in sugar-like colors that over time turn completely white on the surfaces of Faek Rasul’s paintings.

The second event is the decomposition of the corpses of the people that were executed by the Arab National Guardsmen just because they were Kurds. They had been left hanging from light poles in the streets of Kirkuk for days and nights. Their bodies were swollen, deformed and left to the flies. Thus figures enter into the artist’s sensory world[8] and from here the artist drew his impressions that later, in his figurative works “Flight” (1991) and “Waiting for Godot” (1991) reappear, followed by four black and white paintings entitled “Dreams”. As was mentioned in the second part of this article, they all contain a historical dimension.

Of course, the representations of figures and objects do not arise from pure artistic experience, but rather from a subjective experience within history. From a phenomenological point of view, the motif exists as an object in the world. The motif is as it exists in the world, but the rendering is the moment when it is exposed to the artist’s sensations, and the moment when the motif loses its original form and becomes an existential subject, a part of being in the world.

Sensation (or perception thereof), as discussed by Gilles Deleuze from the perspective of Cézanne and Francis Bacon, is behind representation. This means that sensation occurs when an object or figure enters the nervous system of the brain through vision. Obviously, Francis Bacon is not very different from Cézanne in this respect, except that painting takes place on two levels: That which enters the nervous system of the brain directly, and that which carries a story and a message and penetrates the brain with force.

Therefore, in the perception of the painter, figure and form face the objects and deformation. On the other hand, forms and figures enter the realm of representation and deformation through movement and the grasping of this movement. It is an existential reflection and confrontation with the world. Therefore, in a painting there are many levels of perception, which are often different from the sensibility that the painter wants to express in figures and forms.

Francis Bacon talks about his painting “Head VI”,[9] in which the sensory impression on the viewer convey more terror and cruelty than screams.[10] Thus, the sensory impression in a painting often takes on several levels, just as in this series of paintings, in which we encounter two concepts: first, the search for transition into another dimension, and second, deformation and disfiguration. It is a distortion of forms and bodies.

Within this Kurdish historical context experienced by Faek Rasul, both forms are distorted and deformed, and the figure becomes a tortured body under the oppression of the region’s chauvinism and fascism. Therefore, the body transforms from a solid body to a “liquid being”, from a concrete figure to a figurative being or to a black spot on the surface of a liquid. All these, in Faek Rasul’s experience, are not only artistic concepts, but also realistic and historical concepts. All this exists deep in the memory, resurfaces in artistic intelligence and manifests itself again in the movement of black spots and gray stripes.

Artistic sensation and feeling, impression and perception are not produced solely by contact with the object or figure itself, for figurative changes do not occur simply because of this. Rather, there is another level, namely phenomena that emerge from the depths of memory into the consciousness of the artist, forms and figures that are deeply rooted in the unconscious and reach the consciousness of the artist at the moment of artistic creation. Therefore, we encounter another sensation, one that penetrates from the inside and reaches the outside and not vice versa. At the moment of viewing, of course, the direction reverses again.

On the other hand, the motifs that were figurative first experienced their form in the real world under the pressure of circumstances. Even among the prisoners, the change of figures and forms was an ongoing process. And here we come across historical moments in Faek Rasul’s biography: In April 2023, in his studio in Vienna, he told me about his experience as a political prisoner, being transferred from the political prison to a prison for felons. There he met some inmates who were in for murder, rape and theft. Most of them were mentally unstable. Faek said, “If you walked past one of them, you had to turn away immediately so that you wouldn’t get a razor blade in your face. Under the name of “razor blade party,” they even held a self-harm event, a horrible, bloody celebration and gruesome sadomasochism ceremony.”

In the 1980s, when the “Baathists” imprisoned him for membership in the Kurdish party “Komala”, he saw the bodies of people forcibly changed under torture in prison: In an interview for another article we organized together in early April 2023, he told me how a prisoner was tortured before his eyes. He said, “The prisoner was a strong, muscular young worker who didn’t know why he was locked up. They tortured him in front of me to break my courage. The young man was a worker, he had a strong physique, but soon his body became loose, he couldn’t move and finally he died.”

In historical retrospectives, however, it is not only a matter of empirical deformation and “figurativeness,” but also of the transformation of objects, such as those of the walls. Here, the perception of objects shifts into a new realm. The artist’s personal, historical memory reveals another experience. The walls of the prison were filled with carved engravings showing the names, places, and times of execution of the prisoners. Such a wall no longer fulfilled only its old function as a prison wall; it was no longer just an object of apathy, but part of a demonstrative representation of the prisoners’ life story. Thus, objects and figures of fascist oppression were deformed everywhere. No longer does a figure remain the same, nor does an object retain its own appearance, they all become red, black and gray stains and wander through the spiritual phases of memory.

7

But how do you turn into a black spot? How does the world become a gray circle exactly as Faek Rasul has depicted it in this series of paintings? How does the figure “body” change from a red stain into a black stain, which afterwards floats on the surface of the painting as if in water? Or how do these stains even advance into the spiritual realms?!

In the memories of the Kurdish and even Iraqi generations of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, red has long since lost its erotic power. Red is now the color of death, murder, and bloodshed. Francis Bacon believes that there are many different levels of sensation, or rather, perceptions. In this sense, black becomes the color of death and destruction and gray becomes the color of piles of rubble and rising smoke.

We remember Iraqi television during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s. At that time, Iraqi television showed reports from the battlefields. The gray smoke, and black color reflected the blackness of the tanks, armor, and bloated bodies exposed to the sun, rain, and thunder. Black symbolized the destruction of objects and the disfigurement of swollen bodies. Thus, in the collective memory, the color red, the predominant gray smoke and the black spots became symbols of memory, destruction and war. This black color entered the Iraqi and Kurdish consciousness, but without aesthetic power, merely as tragedy.

Another traumatic event in the memory and history of violence during the Baath dictatorship in Iraq from 1963 – 2003, which continues to reverberate to this day, was the “acid bath” that I reported in two articles in Kurdish[12] and English[13] in connection with the statue of Ahmadi Dalak.

The story of the monument of Ahmadi Dalak even shows how the body turns into a black stain. The story was as follows: After the Baath Party security forces captured Ahmadi Dalak; the executioners first took out his eye to intimidate his communist comrades. However, Ahmadi Dalak refused to reveal the names of his comrades to the Baathists and their executioners. On the orders of Nazim Guzar (1969-1973), the Iraqi public security chief who was later assassinated by Saddam, Ahmadi Dalak’s eye was removed. They left him with a bloody eye in his cell for several days without medical treatment and paraded him in front of his comrades. The executioners could not break his courage, so they threw him into an acid bath on the orders of Nazim Guzar, the head of the Iraqi security service. In it, his red body was reduced to black spots, which were also dissolved in the acid.

The painter and sculptor “Baldin Ahmad”, the little brother of Ahmadi Dalak, created a sculpture dedicated to this story This sculpture restores to a world the peace that it itself has long lost.

So the stains flow from form to ideas, and the objects are washed away in memory. Where do they go? Of course, they will split up and the individual parts will, even harmoniously, regroup among themselves and start all over again. Now we no longer behold figures, but rather something figurative in the form of spots. In this way the black spots prepare the ground for the gray tones of the thoughts and souls of our world.

Frankfurt, July 2023

https://heyzine.com/flip-book/f07250ad9c.html

[1] Faek Rasul, Erinnerungen – paintings from 1980 -2006

[2] Matisse, Henri. About Art. Diogenes Verlag, 1993, p. 191

[3] Sloterdijk, Peter. Who Hasn’t Thought of Grey Yet? Suhrkamp Verlag, 2022, p. 15.

[4] Sloterdijk, Peter. Sturz nach Vorne: The Terrible Children of Modern Times. Suhrkamp Verlag, 2014.

[5] Sloterdijk, Peter, and Hans Jürgen Heinrich. The Sun and Death. Suhrkamp Verlag, 2006.

[6] Traska, Georg. “Faek Rasul: Memories of Violence Transformed in the Materials of Painting.” Unpublished essay, forthcoming

[7] Hamalaw, Ismail. “The Story of Fire and the Wall, the Story of a Painter.” Unpublished essay in Kurdish – 2023

[8] Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, pp. 25-30.

[9] Bacon, Francis. Head VI (1949). Arts Council Collection, London

[10] Hamalaw, Ismail. “The Story of Fire and the Wall, the Story of a Painter.” Forthcoming 2024

[11] Hamalaw, Ismail. “The Cynical Smile of a Solitary Head.” Culture Project Online Magazine, September 2021. http://cultureproject.org.uk/the-cynical-smile-of-a-solitary-head/ Accessed August 2023.

[12] Hamalaw, Ismail. “Sculpture and Soul, a Look at the Smile of Ahmadi Dalak’s Sculpture.” Culture Magazine-Culture Project Online – Kurdish, October 2019. http://cultureproject.org.uk/kurdish/satute-of-halaq-baldin-ismail/ Accessed August 2023.

[13] Ismail Hamalaw, The-cynical smile of a solitary-head, published on culture project online magazine, September 2021.

http://cultureproject.org.uk/the-cynical-smile-of-a-solitary-head/