4,972 Total views, 3 Views today

By Fiona Crouch

When my children were small, we lived a few miles from Stonehenge, the UNESCO World Heritage Site, nestled in Wiltshire’s rolling hills. We used to visit often. My children hardly paused to look at the eponymous stones that usually mark the highlight of any visit. Instead, we had to rush past these to return to the reconstructed Neolithic houses by the visitor centre. Every time. From toddlerhood, they were entranced by these little dwellings. I always wondered why this appealed more to them than the wonder of the majestic stones that towered over them. We moved away from Salisbury and I stopped puzzling over this preference.

When I started to research Sakar Sleman’s work, I realised one of the attractions of the Stonehenge dwellings: relatability. For most people, for art to be accessible, especially emotionally accessible, they need to be able to relate to the piece, to connect with the artist. For my children, the prehistoric homes appealed because they told them about the daily lives of families, a hearth and home narrative that they could reconcile with their childhood, albeit from earlier millennia.

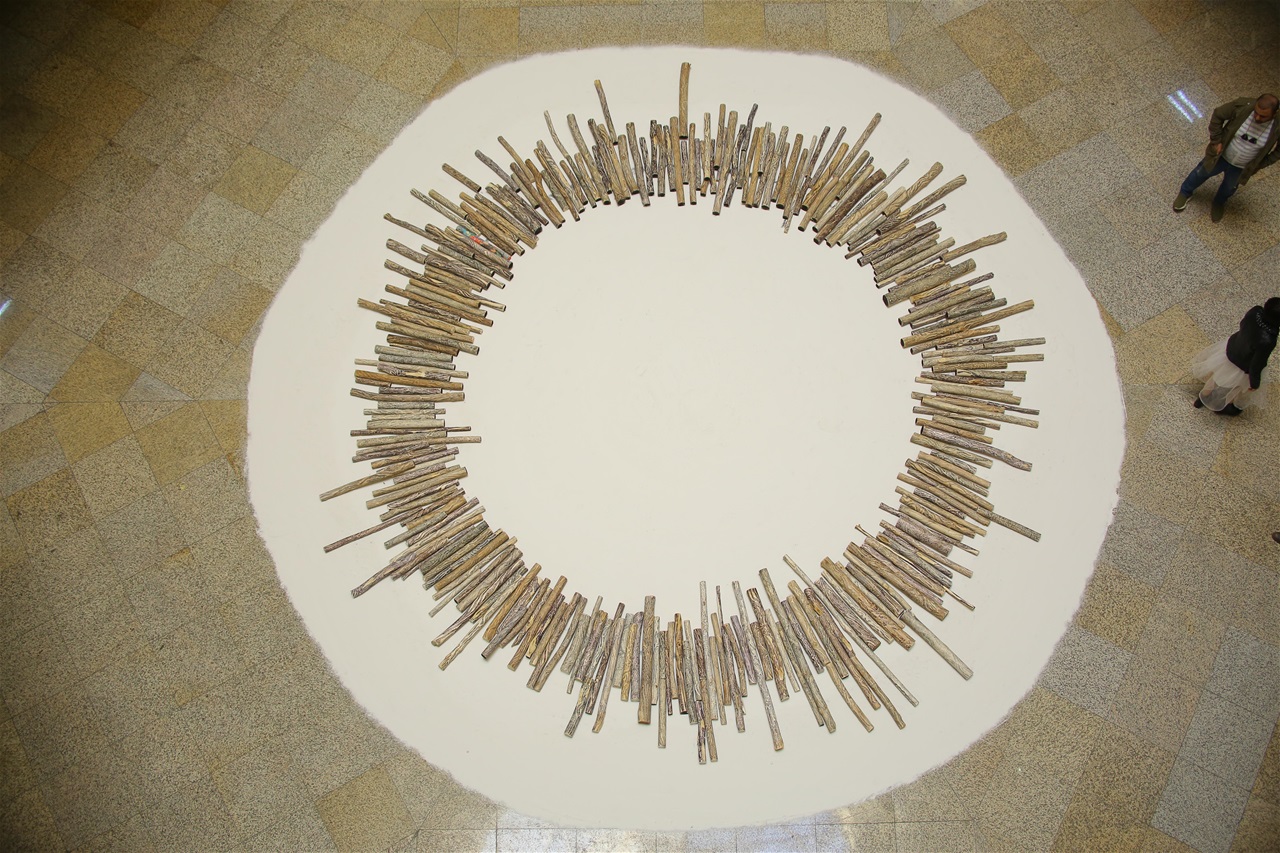

One of Sakar Sleman’s most recent solo shows is staged in a nineteenth century Ottoman Turkish bath. The venue, Hamam Kifri, is located in Sulaymaniyah Province of Iraqi Kurdistan. On an aesthetic level, Sakar’s 2017 the Hamam Kifri installation reminds me of the interior of Stonehenge’s recreated houses. The simplicity and clean lines of the Hamam Kifri’s features visually appealed to me as I researched this review, along with recalling cherished memories of long ago travel adventures. Although I’m not a regular Hamam visitor, I have been to Hamams across the Middle East and I loved becoming an adopted member of a female bathing community. The sense of relatability drew me in to Hamam Kifri.

Paradoxically, one of the other draws of the replica houses at the Stonehenge visitor centre for my children was their strangeness: the chalk daubed dwellings were unfamiliar enough to provoke their curiosity (one of their favourite pastimes was waiting in silence to see if a resident mouse scuttled by our feet). As my children grew, their physical perspective also changed and they noticed new features or stopped seeing old favourites. When Sakar decided to use Hamam Kifri it was a forgotten place, derelict. She chose to use this as an exhibition space (the Hamam is also part of the piece) to encourage visitors to develop new understandings and experiences of the Hamam as well as prompting personal and collective memories of local heritage and culture. Again, this resonates with Stonehenge’s experience. Until the twentieth century it was an overgrown and neglected site, visited and valued by a few antiquarians and archaeologists. Exploring or rediscovering a forgotten venue is magical, like being in a fairy tale. I felt the same quality as I looked at the Hamam Kifri exhibition photos.

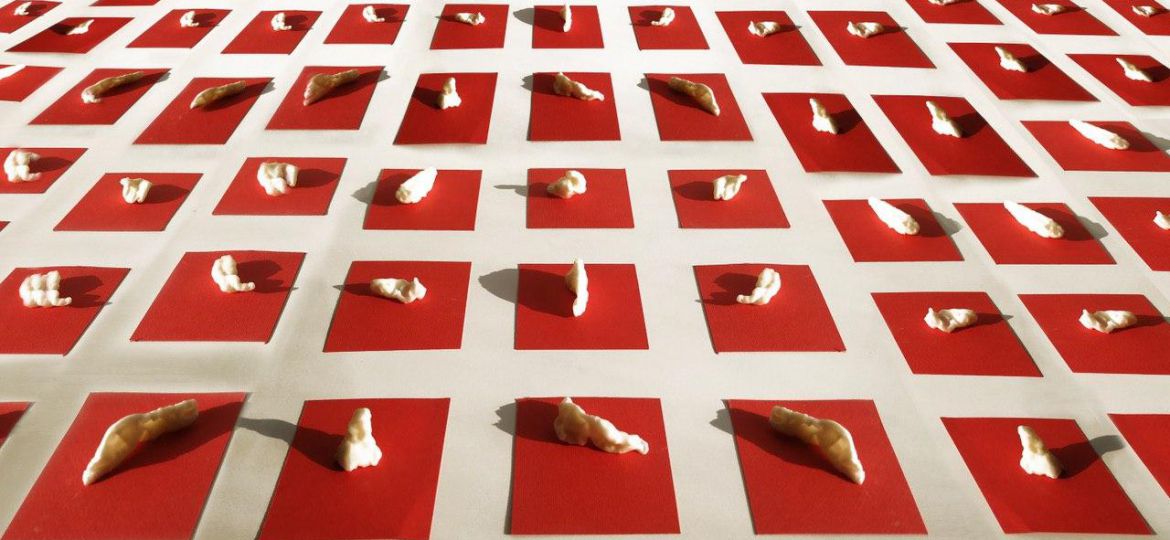

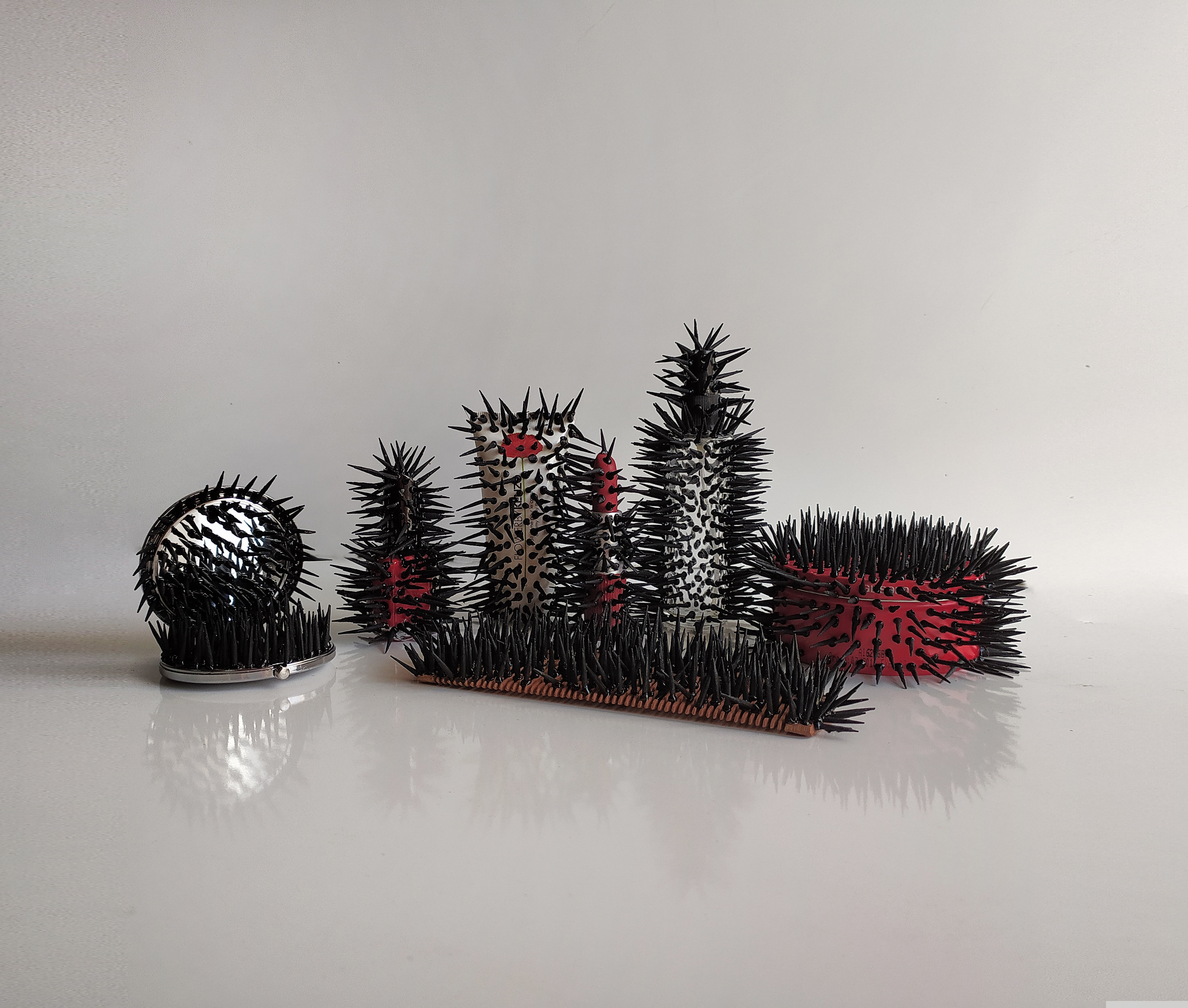

Another piece of Sakar’s work that combines relatability, unfamiliarity and nuanced interpretations is Sorrow (2020). This artwork features red patent leather shoes pierced by toothpicks. There is a similar otherworldliness to this piece. I keep returning to a photo of the shoes; each time I realise a new interpretation. On a superficial level, again, prompted by relatability, Sorrow made me smile (now that’s an oxymoron!), as the day I started to put pen to paper for this article, a colleague came to work wearing the most amazing red, high-heeled shoes. She said wearing the shoes made her feel good about herself. However, I’m a flat shoe wearer, and all high-heeled women’s shoes bewilder me and, even seem slightly menacing. Red high-heeled shoes conjure highly sexualised images in my mind. Are the toothpicks there to protect the wearer from unwanted and unwarranted responses from men or are they barbs that are attacking the wearer for daring to flaunt her sexuality? Viewpoint is everything. Who decides which perspective is most valid?

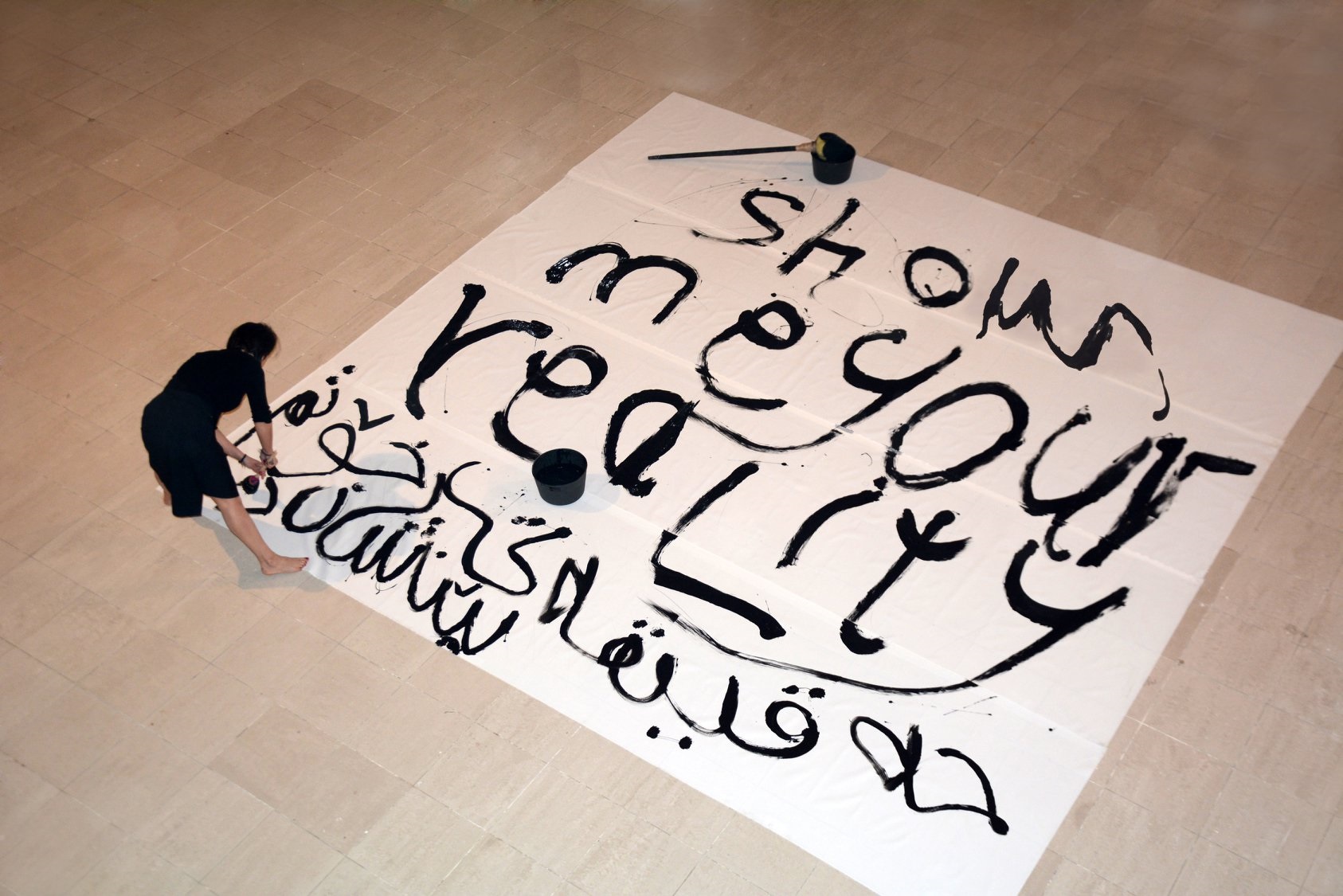

I write this article in the aftermath of the disappearance and murder of Sarah Everard, the allegations of police brutality at a vigil to mark her death and subsequent Kill the Bill protests. These tragic events have made me realise that not only can our physical perspective change as we grow, how we view and scrutinise objects or events, our metaphorical perspective can also alter. If I had written this article a month ago, I might not have detected the overwhelmingly male audiences watching Sakar’s performance art in Tarkib or paid as much attention to the men in military and security services uniform wordlessly surrounding the elfin woman in white in central Baghdad as she paints and then paints over slogans; removing them from sight. Part of my visceral response to this action or writing and then obscuring slogans is to notice the transience of the spoken word; how what we say can be fleeting. However, the impact of these words can be everlasting, especially in cultures such as Kurdish which have strong and rich oral traditions. The backdrop to this performance artwork is Baghdad’s Freedom Monument (Jawad Selim’s masterpiece that was commissioned in 1958 in anticipation of Iraqi’s glorious and harmonious future). The symbolism of the setting is pronounced. In today’s Iraq what does freedom mean, who is free and at what cost? Indeed, one of the recurring themes of Sakar’s are the ongoing issues and inequalities in Iraqi society, in particular those that affect women.

The Baghdad piece is Sakar’s work at her thought provoking and nuanced best: a simple concept executed with panache but multi-layered, enabling the audience to make their own meaning of the piece. I am privileged and grateful to live in a society that allows freedom of speech, where the presence of security forces is normally a reassurance and not threatening, with health care and education available to all. Simultaneously, I question the equality and fairness of my own world and lived experiences. If Sarah Everard had been a young BAME woman, a traveller, a prostitute, a drug user or alcoholic, would her death have prompted the same outrage? The likely answer to this question angers me and underscores the need for artists, who offer different perspectives, like Sakar, to question and challenge the status quo in all societies.

Sakar Sleman was born in 1979 in the city of Sulaymaniyah in Kurdistan where she lives and works. She graduated from the Fine Art College-University of Sulaymaniyah in 2005. She studied at UK’s Newcastle University INTO in 2012. Sakar is a painter, sculpturer, video, installation and performance artist. Her work focuses on social, political, religious and day-to-day issues in Iraqi and Kurdish societies with particular focus on women, memories, war and trauma. She, regularly exhibits her work in solo and group exhibitions in Kurdistan and abroad.