5,483 Total views, 1 Views today

By Fiona Crouch

Balla Ahmed was born in 1987, in Rania, a town in Iraqi-Kurdistan. She graduated from the Art Institute of Erbil in 2007. Since then she has regularly exhibited her artwork, both in collective and solo shows. Most recently, in 2021, her solo exhibition, Rosery Projeckt, was sponsored by the Goethe-Institute Iraq.

Rania is sited on a fertile plain, surrounded by the Kewa Rash, or Black Mountains. It is an ancient town that stood on an ancient route between Mesopotamia and Iran. Rania’s residents are a product of its geographical location and proud history; they are renowned for revolting against tyrannical Iraqi regimes. Indeed, Rania is often referred to as Darwaza-I Raparin or the Gate of the Uprising.

This sense of rebellion, even subversion, rises from Balla’s work – the meaning of each piece is obfuscated[1]. I am mesmerised by every piece, always rich in texture and colour; drawn in to try to figure out its meaning. Sombre, earthy tones, with deep blue skylines, form the setting of many of Balla’s paintings. Is this what she remembers from her childhood, the heavy fecundity of farmland juxtaposed against stark Black Mountains, or is it an artistic trope to accentuate the overall impact of each piece? The predominantly dark, muted colours are picked out with flashes of light and flecks of vibrant colour. Are the patches of light breaking through the darkness, or is the dark snuffing out the light of hope?

The heavy texturing of many of Balla’s pieces evokes Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionism. The flecks and texturing used by Balla are more than an artistic feature, they add movement and create a veil-like effect, detaching the viewer from the subject or subjects of each painting; the audience is cast as a voyeur, watching the performance of each painting.

At the heart of much of Balla’s art is an exploration of challenging issues, especially religion. Does religion succour or suffocate? Does religion lift people up, or trap them? Many of her pieces feature prayer beads; sometimes worn, sometimes as the subject of her artwork. Prayer beads are used in a number of religions from Catholicism to Buddhism to Sikhism to Islam. This familiarity makes these paintings accessible and familiar to a global audience, perhaps also commenting on the powerlessness that many people feel in the face of religion. When a set of prayer beads is worn by one of Balla’s subjects, they appear enlarged and dominate the person or people wearing or holding them. In many of her paintings, the prayer beads seem to be animated, and act of their own volition (this contradicts the mien displayed by many people in her paintings, who seem passive and lacking agency).

Using a different style, Beyond Clothes is replete with symbolism, both religious and political. At first sight, my mind wanders to Klimt’s The Kiss. However, the golden Klimtian background is replaced by threatening grey undertones. As in Balla’s other pieces, there is a sense of menace, but where does this emanate from? On this wall-like backdrop, I glimpse emblems associated with capitalism, communism, Judaism, Islam and Christianity, a post-modernist heraldry of belief systems that Balla is critiquing. The symbols seem to be hastily scratched onto the painting’s surface, like graffiti tags. The mixed media dress that dominates the canvas seems to move, but is limbless; haunting the canvas. Blood drips down the torso to complete the ghostly effect. Is she the victim of these belief systems or does she portend their end? Does this lend an air of desperation or defiance to the piece?

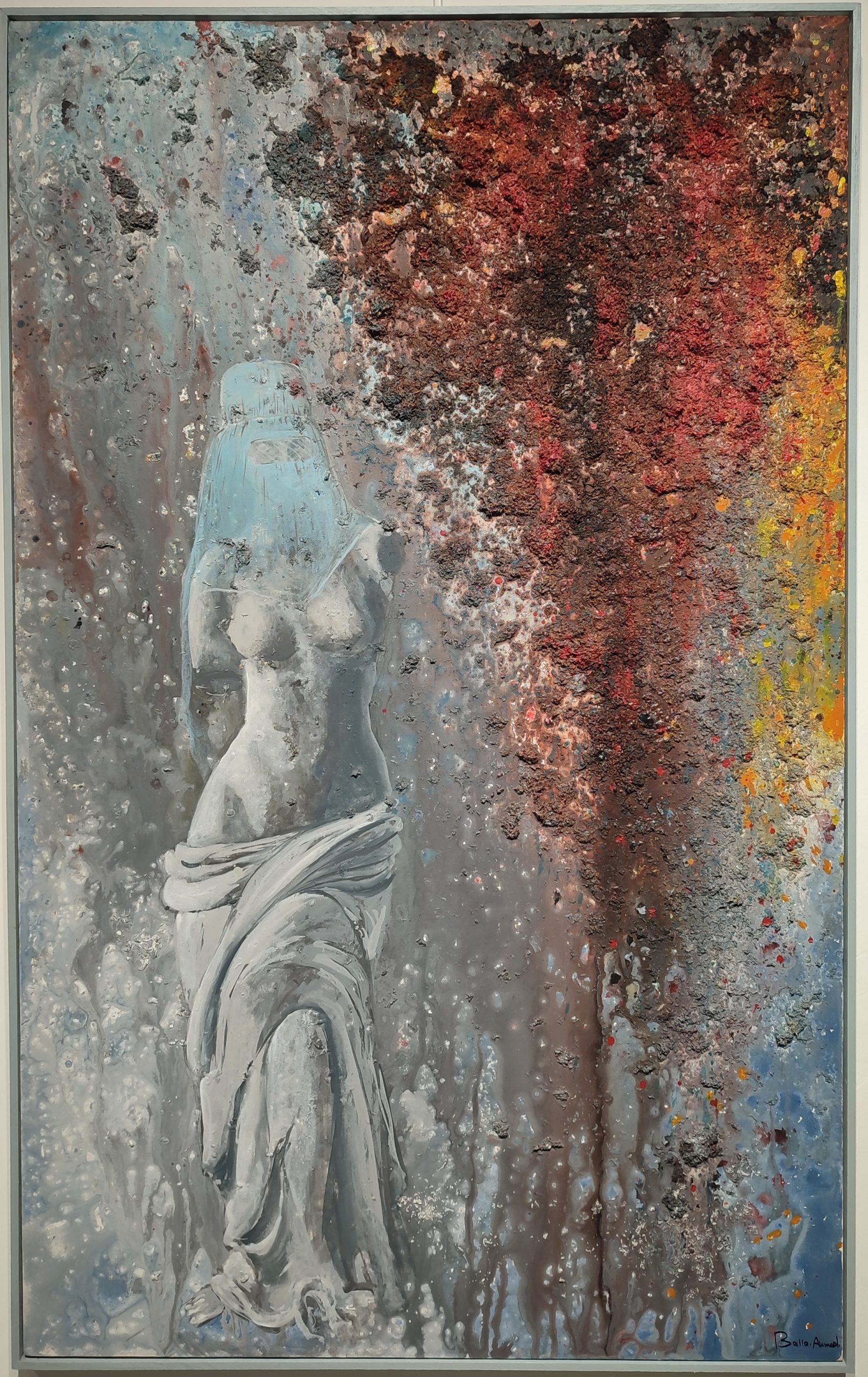

As I study (Blue Venus), I feel as though I am invading someone’s privacy. At first sight, the focus of the piece seems to be a statue of a woman in a classical Greek or Roman style, literally presenting women as a trophy or an object. The statue is composed of white stone; she is naked from the waist up, and the lower half of her body is covered with languorously draped material. With her curvaceous form, the statue celebrates her fertility and femininity. Her posture, especially the positioning of her legs and hips, invites the viewer to acknowledge her sensuality.

As in Balla’s other artwork, there is a dualism to the painting. As well as portraying her allure, the statue’s captivity is also highlighted. Her face is mainly masked by a burka-style covering. On closer inspection, the eyes are not the unseeing, empty vessels of a statue. Instead, they are lively: she is a real person. Her arms are severed like those of many ancient statues. However, as my gaze lingers on her left arm, it is as though it has been cut off as she reaches out to her audience from her canvas prison. The top right hand corner of the painting is heavily textured, and this is the direction of her stare. Is it rust-coloured to represent the decay and rottenness of humanity, or is it the colour of menstrual blood? Is this a commentary on the treatment of women in many societies? Does she stand for everywoman, subjugated by unseen patriarchal forces that fear her female power and strength? Yet, she does not invite sympathy. As I look at her, I feel only admiration. For me, she represents a long line of women, from ancient times to present day, who have withstood conflict and oppression. Perhaps she stands for a long line of Ranian women who have opposed repression. I am prompted to recall a well-known Maya Angelou quote: ‘We may encounter many defeats, but we must not be defeated’. Sometimes, survival is victory: standing up against tyranny will yield results.

[1] One painting includes a detail that apparently defies logic – the shadow of one prayer bead seems to appear on the ‘wrong’ side compared to the shadows of the other prayer beads on the string. This small detail has captivated me!