6,016 Total views, 1 Views today

On the artwork of Baldin Ahmed,

“The spirit moves the matter…”

Peter Sloterdijk*

An essay by Ismail Hamalaw

A solitary head sits atop a chair, face smiling, eyes observing the space ahead of it, dividing it into two spheres–historical and artistic. I found the sculpture difficult to decipher initially, its right cheek resting against the metal of the chair, face fixed in a gentle smile that seemed to communicate tranquility at the crowded main street, as if nothing had happened, no one had been harmed, no tragedy had occurred. It even seemed romantic, the quietly smiling head of the Ahmadi Dalak monument, a creation by renowned Kurdish artist Baldin Ahmed.

The sculpture was erected on (29.10.2019) and is located in Sulaymaniyah, on the west side of the sizable hill not far from the city’s main street. Above it, on top of the hill, sits the hotel Share Jwan, or “beautiful city”.

Sulaymaniyah: birthplace of Ahmad Dalak

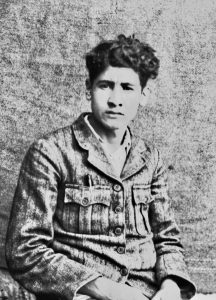

Ahmadi Dalak (Ahmad Mahmoud Ahmad) is the eldest son of Mahmoud Dalak, the first barber of the city. Ahmad was born in the neighbourhood of Kani Askan, in the city of Sulaymaniyah, in 1928.

The city, which served as inspiration for the sculpture, was founded in the late eighteenth century.It was caught politically between the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Dynasty. The Ottoman Empire controlled the city until the end of World War I, at which point the British took over. Most of the soldiers in the British forces were poor men from India, who arrived accompanied by “civilised” officers, whose presence would only establish political chaos. The bombardment of Sulaymaniyah in 1924 by the British RAF was the introductory gift to the Kurdish city that would set the stage for things to come.

The bloodbath of 1930 in Sulaymaniyah was another, similarly gentle answer to the peaceful demonstration of the city’s inhabitants, who had called for an end to the colonial domination and occupation of the city. (Andrew Green, 2014([i])

The tragedy began with the bombardment of the city simply because the Kurdish people disagreed with the new geopolitical map suggested by British officer (Gertrude Bell) and war generals, which forced Arabs and Kurds, Assyrians, Yazidis, Shiites, Sunnis, Christian, Jews, and other ethnic groups to live forcibly together under the umbrella of King Faisal, whom the British had brought from Saudi Arabia. The British army squashed the resistance of the 1920s, which arose in protest of the British colony in southern Iraq. They also killed and bombed the Kurdish people in their own homes. Even Winston Churchill suggested the use of chemical weapons to put an end to the Kurdish struggle in the North, which would force them to abide by the new British map and abandon any hopes of an independent Kurdistan.

From that time, within the newly created state of Iraq, there raged a battle between the central government and the inhabitants. (Raed Asad Ahmed, 2014)[ii]

The military coup in Baghdad, on 14 July 1958, resulted in overthrowing the Hashemite monarchy, which had been established by King Faisal I in 1921 under the auspices of the British. Afterwards, there was the coup of 1963, followed by the 1967 coup in which the Baath party took power.

It is against this historical backdrop that the story behind the sculpture “Ahmadi Dalak” took place. (Moments in U.S. Diplomatic History)[iii]

In this bloody period of Iraqi history, during the struggle for liberation and independence, especially post-World War II, Ahmadi Dalak appeared on the political stage as a leftist, active in the Iraqi communist party.

His family name, Dalak, means “barber” in Kurdish. His father was the first one in Sulaymaniyah to establish a shop especially for the purpose. Prior to that, barbers carried their equipment in a small bag, and they brought their work with them to customers’ homes, to street corners, to door fronts, working wherever they could. Ahmad Dalak’s father brought a special chair and large mirror from Baghdad. He rented a shop in the 1930s, which became the first barbershop in Sulaymaniyah. In honour of this, the family received the name of Dalak.

Ahmadi Dalak would help his father in the shop. Throughout his childhood, he came into contact with many special customers, including politicians, writers, and poets such as Abdulla Goran and Fayaq Bekas. The conversations he overheard, on politics, poetry, dreams of an independent Kurdistan, of modern life, democracy, and the need to resist against British colonial rule, would all have a significant influence on the young Ahmadi Dalak.

The political body and the invisibility of the real body

Dalak became a member of the Iraqi communist party, actively participating in demonstrations against the colonial power of the central government in the 1950s. In 1952, a demonstration took place in Baghdad, during which police shot a young Kurdish demonstrator from Sulaymaniyah. On the day of the funeral parade in Sulaymaniyah, Ahmadi

Dalak gave a speech that would make him a target of the Iraqi intelligent service. This forced him to go underground, moving from city to city in Iraq and changing his name and identity many times.

During the era of military coups, he was the most wanted man on the list of the brutal intelligence service. He led a secret life, resorting to clandestine action. The secret police managed, nevertheless, to capture him many times. They placed him in prison and tortured him repeatedly. He was in prison during the monarchy and even during the coup of 1963. His last imprisonment was in 1969, when the Baath Party was in power.

That year, his execution was ordered. Nazim Guzar, his executioner, ordered that his body be slowly emerged in a bath of acid. It was this defining moment that served as inspiration for Baldin Ahmad’s sculpture of the disembodied head.

The artistic moment of Baldin Ahmad

The passage from historical to artistic moment occurred at this point, with the disembodied head, as artist Baldin Ahmad recalled forty years later.

The pleasant, handsome face of the revolutionary man whose smile perished through brutal, Soviet-style torture and who fought for liberation, not only for a Kurdish nation but for the working classes of the world, is immortalised through this sculpture.

To understand the historical encounter between executioner Nazim Guzar and revolutionarily prisoner Ahmadi Dalak, it is necessary to examine the macabre moment that the artist would capture, the moment in which Ahmadi Dalak’s body separated from his head, the last part to remain above the acid bath.

Ahmadi Dalak’s execution was the result of millions of dollars spent by Saddam Hussein to finance apprenticeship programmes in the “Soviet Union” to train the secret police in torture.

Guzar was one of the officers whom Saddam Husain had authorised to kill, torture, mutilate, melt, and crush anyone who dared to whisper against him and his Ba’ath party (Shawkat xaznadar,2005 )[iv].

If we look back at the history of Ba’ath Party, from when it first came to power in 1967, Saddam Hussein’s first urgent decision as vice president was to bestow the rank of general on Nazim Guzar, despite the latter not receiving formal training at any military or police academy.

Nazim Guzar became the director general of the secret police in Iraq. According to former Baath member Hadi Alawai who was also journalist at the time, in 1969, Saddam was convinced that Nazim Guzar could achieve the best results in bringing political prisoners, especially members of the Communist Party, to confess and give up the names of their comrades who were clandestinely active against Baath regime. (Hadi Alawai,1990)[v]

Guzar’s brutality, ruthlessness, and bloodthirsty character was enough for him to attain this position as general director of the Iraqi Secret Police. His brutality was exactly what Saddam Hussein needed at the time, but it was also the nature of Saddam Hussain to kill anyone who tried to achieve more than what he had ordered them to do.

According to the Baath government official story, Nazim Guzar had tried to assassinate Iraqi’s president general Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr on 30 Jun 1973, when he returned from an official visit to Bulgaria. He was captured after trying to escape to Iran. In an ironic twist, Saddam employed the same method to execute Nazim Guzar which the latter had used against prisoners in his time of glory. There is a rumor that Nazim Guzar was raped repeatedly before his execution. In only this brief history, the cruelty of the Baath party is abundantly evident.

The historical moment

In order to understand the sculpture, it is necessary to examine the historical context that led to the fatal encounter between Nazim Guzar and Ahmadi Dalak.

In 1967, there was a split within the Iraqi Communist Party. The group that left called themselves the “Central Command”. They tried to established connections with partisan cells in the south of Iraq, especially in the Marsh areas of Nasiriyah.

Ahmadi Dalak was one of these leaders who engaged in partisan actions against the Iraqi secret police in the Marsh areas. In a short time, however, the Ba’ath regime managed to capture all the leaders of Central Command and put them in Baghdad’s secret police prison. The members of the Central Command were tortured, and many of them gave up the names of their comrades, or were killed under torture. Nazim Guzar spearheaded the confession processes.

It was essential for the Ba’ath party that the leaders of the Central Command give up the names of their comrades and confess publicly that they had made a mistake in opposing the government. Saddam Hussain promised the leaders that he would spare their lives, offering to secure their financial futures too, in addition to giving them positions within the government. Aziz Al Hajh, Secretary General of the Central Command, confessed publicly, and Saddam rewarded him and sent him to Paris as Iraqi ambassador in (UNESCO) until his retirement. (Aziz Al Hajh, Interview)[vi]

It is clear that Ahmadi Dalak had the chance not only to keep his life, but to exploit that generous opportunity that Saddam had offered. He ultimately refused, insisting that the Ba’ath party and its government–especially Saddam Hussein–were leading the country to war and destruction. He posed a challenge to the bloodthirsty Nazim Guzar, refusing to name any of his comrades. Nazim Guzar ordered that he have one of his eyes removed, leaving him to bleed in his dirty cell for many days. After that, they put him on a chair to be displayed to his comrades in the prison. This act of terrorizing other prisoners was method for which Nazim Guzar became famous. It led many to confess, not just to save their own lives but at the very least to ensure a quick death, free of brutal torture.

Aziz Al Hajh was one of the prisoners who saw Ahmadi Dalak. After witnessing this, he confessed publicly on an Iraqi TV channel. Which eye was removed remained a mystery; not even Dalak’s family was given any information. They did not receive his corpse for the simple reason that there was nothing left to hand over, except the acid water in Baghdad’s secret police headquarters’ torture chamber, which was used to melt many a prisoner before Dalak.

The solitary head and the “anatomic” chair

At the intersection of history and art, artist Baldin Ahmed captured the last moments of Ahmedi Dalak, the moment of the prisoner’s last sentences, of his cynical smile on the confession chair in the torture room.

It was the fact that Ahmadi Dalak was smiling all the time, never displaying any weakness or regret, that made Nazim Guzar lose his mind and torture him even further.

At last Ahmadi Dalak agreed to confess, but on one condition: that all the higher officers should be present in the room. According to many accounts, Saddam was convinced that Ahmadi Dalak was not the sort of man to back down easily. It was for this reason he didn’t appear in the acid room, which was the last stage of the tragic theatre.

The day came. In addition to Nazim Guzar, there were many officers present at the scene, who would later go on to recount this story after witnessing it. They put Ahmadi Dalak on the small, dirty, bloodstained chair. He was in a profoundly lamentable condition. There was a cold silence in the acid bath room at the time of confession. The officers for waited the moment of victory, when at last Dalak would confess. A cynical smile appeared on his face and he spoke his last words: “As a communist, I fought all my life for equity and liberation. Even if I were to be born again, I would relish being born as a communist to continue the fight for liberation. Gentleman, this is my first and last confession”.

According to the many witnesses, Dalak did not lose his temper, his cynical smile, his confidence, even when he was on the horrible, small chair, his eye, his face, his nose, his entire body covered with blood from continual torture.

At that moment, the chair and the body fused together, melted together, historically and biologically, for two reasons. Firstly, the small chair offered him the last historical stage, the last battlefield against dictatorship, the last chance to valiantly defy the chauvinism of the Baath party in their proud terror castle, personified in Nazim Guzar and his master Saddam Husain. Secondly, the chair was the last object, to touch his body, his biological roots. More precisely, the small chair is proof that the body was here with the entirety of its flesh and blood. The chair was the last place to hold Dalak after his torture and confession.

The chair was a witness–everyone who related his story mentioned how Nazim Guzar avenged his defeat, ordering his men to take Ahmadi Dalak and dive him in the acid bath, gradually, from his feet to his head.

Two things remained from Ahmadi Dalak. One was the chair, which was covered with his blood. The other, was the solitary head without a body. These two objects engendered the moment of the sculpture called “Ahmadi Dalak”.

Talking to death

Our artist Baldin Ahmad described the chair. It was no mundane chair; it was covered with Dalak’s blood, with his DNA. Baldin Ahmad recalls that the family did not receive the body simply because nothing from his body remained after the acid bath.

Baldin remembered his early years and how his brother “Ahmadi Dalak” had gifted him a pen; he recalled the smile that would come to his face when they spoke about different matters in life. After his execution, the entire family lived under horrible shock because there was no grave to go to; there were only shadows, sounds, whispers, stories about him and Nazim Guzar in which Ahmadi Dalak turned into a dead shadow who would visit and speak with Baldin.

This artwork is based on one such a conversation from beyond death, the conversation that Ahmadi Dalak was not able to finish with his brother, the sort of conversation the living sustain with their loved ones who have travelled to the world of the dead. Baldin was greatly impressed with Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italian film director, novelist, writer, and intellectual (1922 – 1975) who worked on this subject. Pasolini’s death itself was an unsolved mystery, a conversation left unfinished.

In one of our many conversations, Baldin Ahmed said: “When I lived in Italy, I was–and still am– impressed with Pier Paolo Pasolini. I followed most of his works. His ideas on death had a profound influence on me: He believed that everyone, at some point in their lives, has the power to hear the dead who have left them. For this reason, I endeavored in my sculpture not to personify any kind of heroism, though Ahmadi Dalak is a universal, revolutionary hero who fought against chauvinism and fascism. I wished, instead to convey this vital energy of life, which emanated from his death. I didn’t want to push any kind of heroism on the surface, no, I wanted to represent his optimistic energy, his warm conversations about the best future for a human being, his exuberant dedication to equality. I wanted to bring to life his conversation from death, which gave me hope and helped me through my darkest moments.”

The hero in empty space

Reliving the historical moment means recalling the hero after his journey in the ocean of the unwritten history. Peter Sloterdijk in his book Weltfremdheit – Unworldlinessrefers to this kind of hero “who is the man who goes ashore from the ocean of despair. In him begins the adventure of civilization as the colonization of the Ego – mainland” (Sloterdjik, 2003)[vii]

Our hero vanished in the chaos of accumulated historical events–wars, mass murders, revolutions, social conflicts–after his death in 1969. After forty years, however, the hero returned to the mainland, not with his entire body, but with his last, remaining part after the acid bath, his head, which rests on what Baldin refers to as the “anatomic” chair–the part that Dalak’s body melted into and which preserved his DNA, the print of his life and existence.

Peter Sloterdijk refers to “the birth of hero” in the momentum of self-discovery, “Selbstfindung” through Suddenness “Plötzlichkeit”. This momentum is “being” or “being’s reflection”–“Sein – Being”–which is the birth’s momentum of the hero in their “I – being / Ichsein”.

Precisely, to understand this in relation to the two moments, historical and artistic, we imagine two sorts of births in two different times. One is the birth of the hero in their authentic historical ground. The second is the birth of the cynical smile on the face of our sculpture.

Of course, the first Suddenness “ Plötzlichkeit” by Ahmadi Dalak was the tragic moment one of his eyes was removed and shown to other prisoners. This was the birth of a hero who “discovered himself” and stood tough against all the tortures and humiliation. He decided, nonetheless, to stay in his chosen path, which would ultimately lead to his death but also to his birth as a hero.

The second symbolic birth was that of his cynical smile, which our artist Baldin Ahmad immortalised some forty years after. The hero interacts with the empty space of his torture and turns it into a stage. “The hero picks up the trail that leads him to the site of the pristine malefaction. He thus returns to the scene his exposure, his bellicose alienation.” (Sloterdjik, 2003)[viii]

Dalak himself created the stage; he was the “stage maker” in the empty space in which he led his killers to sit opposite him and to turn the myth of Nazim Guzar into a historical jock. Through the creation of the cynical smile on Dalak’s face, we perceive the historical moment in which the hero interacts with the empty space of fascism and turns the dead element, the empty space, into a living element.

In order to explain the empty space and dead elements, we may consult Peter Brook’s book ‘The Empty Space” in which he refers to the stage as not only something physical within a theatre, but something that exists everywhere in life. He said: “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged” (Peter Brook, 1968)[ix]

He also imagined that “There is a deadly element everywhere; in the cultural set-up, in our inherited artistic values, in the economic framework, in the actor’s life, in the critic’s function. As we examine these we will see that, deceptively, the opposite seems also true, for within the Deadly Theatre there are often tantalizing, abortive or even momentarily satisfying flickers of real life” (Peter Brook, 1968)[x]

Our hero walked through the empty space and lived with the deadly element that was embodied in Nazim Guzar– the killer, the torturer, the executor, the most frightening man in the history of Iraq. But our hero Ahmadi Dalak did not let the deadly element of fascism fade his vitality, his true optimism, his ironic smile. He turned the empty space of torture chambers, He turned the empty space of the torture room, the empty space of deadly theatre to the living theatre, to the historical moment of self-discovery of his being a hero who sits on the anatomic chair and smiles so cynically at his executors.

References:

* Sloterdijk Peter, 2009:p.195 Du mußt dein Leben ändern, Shurkamp. German

[i] Green, Andrew, 2014, Bombs over Iraq, then and now, accessed website 20.12.18.

http://gwallter.com/history/bombs-over-iraq-then-and-now.html

[ii]Asad, Raed Ahmed 2/11/2014, Churchill, the Kurds and poison gas, accessed website 23.12.18.

http://www.rudaw.net/english/opinion/02112014

[iii]The Iraqi Revolution — of 1958, Moments in U.S. Diplomatic History, access website 23.12.18.

https://adst.org/2014/07/the-iraqi-revolution-of-1958/

[iv]. Alhiwar al Mutamden, Shawkat xaznadar, Sadaam Hussian and Name Guzar and the painful memory – Online magazine -22.11.2018 http://www.m.ahewar.org/s.asp?aid=72137&r=0.

[v]. Hadi Alawai, ,1990 page 47 -48., Iraq as a state of secret organization, Arabic, London

[vi]. Al Iraqia IMN TV – Pr ‘step’ program – Interview with Aziz Al Hajh – part 1- 3

قناةالعراقيةالدوليةIMN– Published on 27 Jun 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VX7L89SQ5iE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1iUnE6xywUQ

[vii]. Sloterdijk Peter 2003 Page 24. Weltfremdheit, Shurkamp Verlg German,

[viii]. Sloterdijk Peter, 2003 Page 21, Weltfremdheit, Shurkamp Verlg German,

[ix]. Peter Brook, 1968, page7.The empty space, Touchstone

[x]. Peter Brook, 1968, page10.The empty space, Touchstone