3,549 Total views, 2 Views today

A review by Sarah Mills of Poshya Kakil’s art work, The Shadow of ISIS

The caliphate is dead. Blisteringly humiliating news that must have been to the militias confident in the supremacy of a reign perpetuated on slaughter and fear of it. A world of enemies was simply unsustainable. But the trauma of the war generation is not so easily erased with a military defeat.

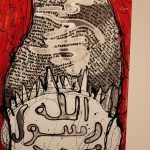

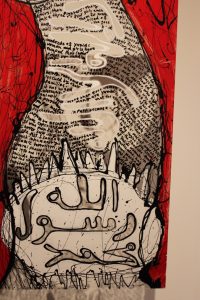

In The Shadow of Isis, Poshya Kakil Ahmed interprets the seismic and bloody events in suspended panels with shocks of red and tall shadows, stealing ‘sacred’ words and amalgamating them with ‘profane’ sexual imagery and stories of victims.

The performance artist from Iraqi Kurdistan brings the realities of the war-torn region to the stage, using her own body as a medium, incorporating music, vocals, and writing to saturate the senses, engaging observers in an intimate and stimulating way. One time-based performance sees her draped in a burqa suspended by a string, which is slowly raised to reveal the woman beneath, dressed in white. She proceeds to use her skin and clothing as a canvas, writing words like ‘Iraq’, ‘war’, ‘honor killing’, ‘woman’, ‘bombing’, ‘blood’ and ‘Quran’ on them – a veritable book of the beleaguered region.

Her artwork in The Shadow of Isis recounts the horrors of 14 women who were kidnapped or sold by Isis, like Jihan, who was sold numerous times before finally escaping. ‘I needed to find a way to tell the stories,’ says Ahmed. ‘I knew that the language of art was the best way to do that.’

Plaintive music sounds. The plexi-glass panels hover in the air; they move as the observer walks past them. Light shines through them, casting shadows taller than the panels themselves, a deliberate effect intended to convey the profound impact Isis’ atrocities have left on the world.

The shadows dance with movement as well, like ripples in a lake when a stone has been thrown, as the artist describes it. A poster explains the plight of women in Isis-controlled territory, where they were sold into sexual slavery in brutal, but normalised, fashion, the trade deeply embedded into the regime’s infrastructure. The atmosphere is sombre, ghostly, and viscerally disturbing.

The Shahada – ‘There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God’ – features prominently on the panels, as it does (did?) on the ubiquitous black flags under Isis’ reign of terror.

This time, however, it is transposed onto phallic imagery and the female form, in black and white, but also bright, bloody, garish red – sacrilege for the believer, but no more than its use as justification, a token of legitimacy, for a cult of death. The prospect of a sexual heaven following martyrdom is enticing and all too human. The knowledge that their death at the hands of a woman bars them entry to this promised paradise fuels Isis’ rage against Kurdish female fighters and other women. Sexual repression and release generate the violence that powers their jihad. A maw of sharp teeth clamps down upon any pretense to piety the Shahada offers. This is a gory, carnal world.

The Arabic writing, which also lends itself to appropriate verticality here, runs down the length of the minaret-resembling phallus in sharp lines like lacerations – a testament to the exploitation of religion for the most heinous acts, like rape and enslavement. The writing recounting the women’s stories winds and weaves, sometimes changing directions. It is impossible to impose direction upon it – as impossible it is to fully grasp the concept or experience of a sex slave in the 21st century. At the head of one phallus is a heavy-lidded eye, eyelashes extending painfully from it like swords. The egregious sins are laid bare now, for the world to see. The significance of sight and visibility is also manifest in the breasts that resemble eyes and the surreal faces – distorted, jarring, and wide-eyed – displayed on other panels. This artwork is an exposé, revealing and detailing, unapologetically bold and confrontational. Red covers most of the panels in proportions ‘equal to [Isis’] most violent acts’, as the artist explains.

It is one thing to see the statistics. The human brain cannot grasp immensity once it surpasses a certain number. But to read even one woman’s vivid account of existence under Isis with no details spared, to behold it in shades of red like bloodstains, to feel the presence of frightened eyes, is to be thrust to the threshold of that existence, without entering it.