3,607 Total views, 1 Views today

By Fiona Crouch

I’ve struggled to put pen to paper for this article. With wider global events, my thoughts and emotions have been in a perpetual churn for the last few months. Rezan’s work seemed to jar at a point when my soul needed soothing. This surprised me. I like art to challenge, make me feel uncomfortable, question the status quo.

Rezan Betoula is a performance artist. She was born in the city of Sulaymaniyah in South Kurdistan in 1986. Sulaymaniyah is a city with a distinguished creative tradition of producing artists, musicians and poets, perhaps the tough mountainous, semi-arid conditions (characterised by long, hot summers and cold, wet winters) has inculcated its people with a need to nourish the soul against the harshness of the environment? Rezan boasts an exceptionally impressive academic record: she gained her undergraduate degree from the College of Fine Arts at the University of Sulaimani before moving to France and achieving two masters degrees from the University of Pantheon- Sorbonne in Paris. Even at the start of her academic career, Rezan was questioning her belief system – her notions of humanity and interpretation of religion (particularly juxtaposed with the Muslim faith she grew up in).

In time she began to identify with existentialism and the notion that each person is a free and responsible agent whose decisions and actions determine their future. Her postgraduate research saw Rezan specialising in visual art and the human body. Rezan freely expresses the impact that the change of cultural environment, as she moved from Kurdistan to Europe, has had on her as a human, a woman and an artist. She highlights how “amid these changes [her life experiences after relocating to Paris] I became curious about identity, body, womanhood. Me, the body, as a subject and object became the core [the focus of her artwork] of my questioning”. As she became more fluent in French she was able to start reading books and articles from the 1960s in which French women were discussing body liberation apparent in feminist art in the twentieth century. “This became part of my new thinking and questions about my body” and “I reached a new stage which is (me as my body) to be used in my art work and sexual identity became a new stream for my work”.

For those who may be unfamiliar with performance art as a genre, it is “artworks that are created through actions performed by the artist or other participants, which may be live or recorded, spontaneous or scripted” (Tate, 2020)[1]. For me, it blends traditional paint-on-canvas type art and the performing arts. I find it difficult to fully appreciate the work of a performance artist at a distance or through a screen (I prefer experiencing performance art in person to sense the atmosphere). However, while researching Rezan and her art, the impact that her work has upon in person spectators is clear: many stand transfixed by her or are very clearly engaged and being active participants in her piece. In TransView (with Sozyar Sdiq at the Pompidou in 2018), I see her as an observer, as part of a crowd, but also alone and detached. Her eyes convey a sense of her isolation. Is this part of her performance, an active choice, or a highly personalised emotional response to how she feels? Interestingly, one of her most recent collaborations (with Pierre Chacart at the Gallérie le Patio in 2020) is Jeu de regards, or the Game of Looks. Photographs of different faces and eyes, mounted on blocks of wood with some mirrored detail, reach out to the spectator. The mirrors enable the spectator to position themselves to become part of the installation – a device that is both simple but clever and effective – life is art and art is life.

Some of her art conveys much a darker sense of what it means to be alive, specifically what it means to be a woman. Using her body as part of her artwork, the focus of most of her pieces, has liberated Rezan, enabling her to develop her own understanding of her body and what it means to be a woman.

L’autre moi (or The Other Me in 2014) chilled me. The layering effect of the installation is characteristically Rezan – simple but clever and effective. Nine photographic portraits of Rezan’s face and upper torso (each taken in the same pose but presented differently) are hung unframed on a pure white wall. Two of these, the tissé portraits (tisser means to weave), seem innocuous at first glance. One features Rezan with a white woven strip covering her eyes and, the other, a strip over her mouth. But a woman who is unable to see or speak because her eyes or mouth are covered suggests the thwarting of women due to their gender (weaving is traditionally been associated with women in many cultures).

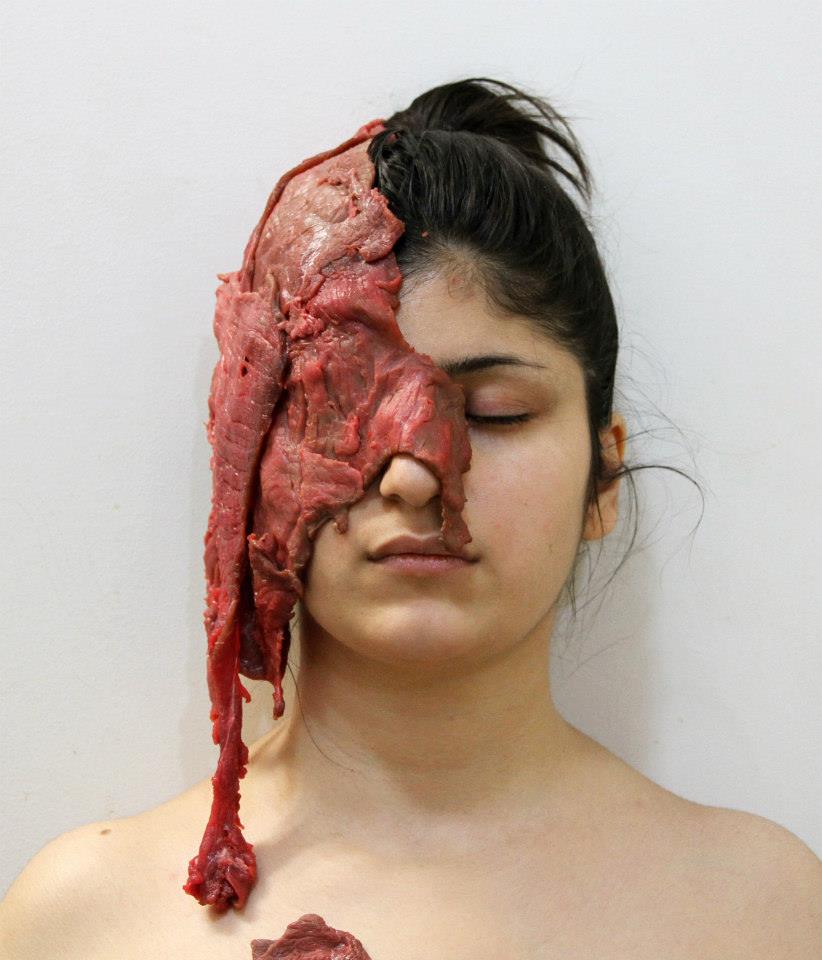

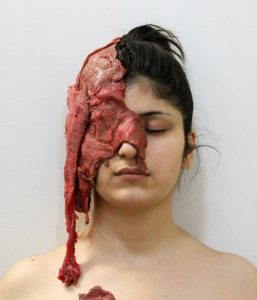

In this piece, Rezan exposes the objectification of women, at worst in this series of portraits, they are slabs of meat. Le hymen (The Hymen) and L’objet de desire (Le vagin) (Object of Desire (The Vagina) feature blood and/or human flesh. In Le non-corps (The None Body) her face is a lump of meat dressed in a chador. As a side note, I’ve not previously noted how some of the most intimate female body parts have been accorded a masculine pronoun: I interpret this as male control over female reproduction and identity.

Yet, this artwork raises more questions than answers: Rezan is not simply out to shock her audience, she’s ensnaring them into embarking on their own existential journey. The prayer rug she has selected to place in the foreground is interesting – it looks like a slightly cheap or tacky souvenir with a built in speaker. To me, this is more a critique of how she feels religion is practised. The use of five candles is attention-grabbing: Muslims do not use light or candles as part of a religious ritual, but they pray five times per day. Does this symbolise how Rezan feels about faith (as opposed to how it is practised by others)? Does praying five times per day lead her to the light? Is she the slab of meat on top of the white piece of cloth carefully placed on the prayer rug? Is this the same cloth that covers her eyes and mouth in the portraits on the wall?

My favourite piece of Rezan’s work is the montage of still images taken from La Lutte (The Struggle) a short digital film produced in 2015. You don’t need to watch the film to be able to sense the movement as she draws with charcoal, the frenzied activity underpinning the artwork. Her own personal struggle springs from the page as she recreates her passionate outburst. Dressed totally in white the contrast between the artist, the canvas and the charcoal strokes is striking. It is this feeling of

purposeful simplicity that has won me over to Rezan’s art. Once I finally managed to write the first sentence of this review, I grasped the impact that her work has had on me – prompting my own questions of identity and journey as a woman. I would love to see Rezan produce and perform in person, to be able to reflect on her message and hone my own meaning of her work. Maybe my soul didn’t need a balm to soothe: perchance I was seeking fresh inspiration to kindle the flames of curiosity.

[1] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/performance-art