10,433 Total views, 2 Views today

By Darya Najim

As world systems become stronger and capitalism projects more cultural and ideological influence, the world finds itself increasingly polarised. You are either on one side or the other, and if you happen to fall in the middle, you might have a problem.

When, in the 70s, the major discourse regarding sexuality–with a focus on homosexuality– began, the Kurds were fighting oppression, as they had always done. In Kurdistan Region, the 70s represented the beginning of the struggle against the Baathist regime. Since then, however, over forty years have passed, and it appears that the majority of its population is still only occupied with nationalist discourse concerning the Kurdish problem in Iraq, which has always been the focus of discourse. This has led to a procrastination of all analytical conversation on the human condition, especially concerning the human body and individual identity. There has thus been a marked void in aspects of the social and natural sciences. While collective identity is in crisis, individuals must ask questions that concern them, as discussion on issues of individual identity is sorely limited.

The ongoing wars in West Asia are a colonial legacy and some of the most problematic manifestations of this legacy lie within the penal codes, by which most countries still abide. Penal codes established by the French in the late 1800s criminalised homosexuality; Iraq and the KRG have no laws that punish homosexuality. But belonging to a sexual and/or gender minority is still fatal.

In his History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault, in what he calls the “repressive hypothesis,” states that for the past hundreds of years any form of bodily pleasure has been either incarcerated into institutions or turned into taboos in an attempt to sustain the interests of the bourgeois. Due to this, personal liberation and individual progress have been limited to what falls in normative frameworks. In Europe, the church demanded that people not only refrain from speaking of their sexual misconduct, but even from expressing thoughts that were sinful and outside of the orthodox chassis. Through medical institutions and judiciary systems, in which individuals would either be convicted or diagnosed when falling short of social norms, sex was furthermore restricted. And on top of it, sexual activity became the basis of morality.

Sexuality is a basis for individual identity, and it is often so associated with gender roles that any discrepancy between them provokes outrage. It is only within the framework of marriage in which two persons of the opposite gender are bound in union that people can become sexually active. However, Judith Butler’s theory of genderperformativity, a term used to describe gender as an identity that society builds up in the individual and the individual in return learns to act upon, changed perception on gender. For example, certain behaviors are associated with femininity and some with masculinity. If a man exhibits any characteristics traditionally associated with femininity, that man must be a freak of nature. Hence, members of male sex are taught to adopt masculine characteristics and thereby fall into gender roles. The same goes for members of the female sex. Any behaviour falling outside of this construct could be either convicted or diagnosed. In an interview, Butler uses the example of the murder of a man with a feminine walk as the ultimate example of the consequences of upsetting gender norms. When society’s constructs in inextricably binding gender to sex fail in an individual, the consequences can be fatal.

The topic of sexuality, whether heterosexuality or homosexuality, is taboo in the KRG. Only recently, through social media, has a small minority of the society been introduced to sexuality and how it influences individual identity. The KRG has no laws against homosexuality, and is actually committed to human rights; to which extent it has been successful is a completely different topic that will not be addressed in this text. The major stigma around homosexuality in Kurdistan is more owing to the fact that it is a form of sexuality. Though there is no state repression of sexuality per se, there is no protection guaranteed to those individuals who deviate even slightly from the norms either. The threat then is not only on the homosexual, transgender, or queer individual, but also on heterosexuals if they engage in sex outside of marriage. Even within marriage, it is still a topic on which people keep silent. Honor killing still plagues women in the KRG who happen to upset cultural norms and the male members of their families, bringing ‘dishonour’ on the family name. Dishonour can simply mean any form of activity between unmarried persons or sex outside marriage.

Institutions, including schools, have contributed in further restricting conversation on sexuality. While schools in the KRG hardly provide any form of education on reproduction, they also segregate students based on sex and, often, female teachers refuse to teach. A teenager whose sexuality is in the process of being formed and who is beginning to question her or his own sexuality turns left and right, and the only direct form of education this teenager gets is through the porn industry. Secondary to the porn industry is religion, which in itself is a major setback to any form of progress. Religious sources have been engraved in public consciousness. Consequently, there is a constant clash between two opposing sources of knowledge that both fail to provide a healthy platform for sexual identity.

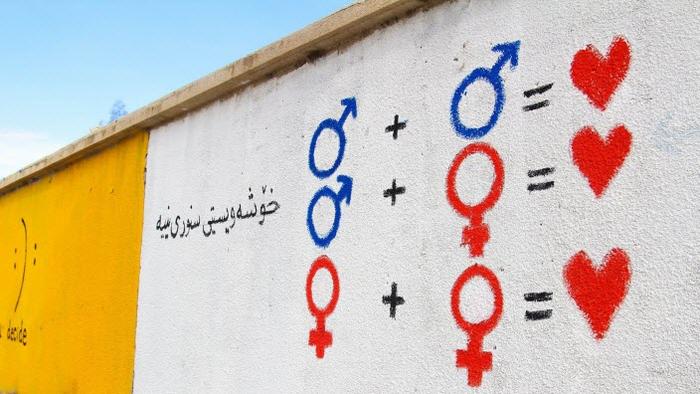

The KRG’s failure to protect the individual, especially women and other gender and sexual minorities, has stained the region. Though the KRG aspires to adopt modern values, it is still run by family ties. So when a member of the LGBT+ is in danger, KRG does not heed to protect this individual even though it does not directly punish either. This passive aggression is all but a death penalty for members of the LGBT+ community. In this way, their voices are suppressed and they will always be forced to live under these oppressive social power structures. Those who are not silent are threatened by individual members of society, religious groups, and family members. Unless there is open dialogue on sexuality, there can be neither collective nor individual freedom. It is important to remember that artificially imposed categories resulted in the unloved other. The rejection of the latter, the different and nonconforming, needs to be the basis on which intellectuals begin earnest dialogue. Though it will undoubtedly upset society’s cultural superego, the Kurdish community worldwide needs to accept that they do not belong to a different race of humankind with no homosexuals and no transgender individuals; there happen to be both in the community. And as Judith Butler would say we must protect their lives.

When Amir Ashour came out, an Iraqi gay man in his twenties, many praised him for his bravery, but the majority clenched their teeth and sharpened their knives. Born in Baghdad and raised in Sulaimani, two major cultural cities in Iraq but still rather conservative, what gave Ashour the tenacity not only to come out as gay, but also to start IraQueer, an organisation dedicated to protecting the LGBT+ community in Iraq and the KRG was a choice between life and death. He could either live as he was, even if that meant putting his life at risk, or he die one humiliating dayat a time.

While the major threat is directed towards gay men, since gay men are usually associated with feminine characteristics and that in itself is seen as shameful, women who in any way deviate from accepted sexual or gender norms are in even more danger. Since the region has a history of honor killing those who are not convicted–and it is a crime hardly criminalised–the threat on women is twice as serious. There are hardly any women who come out as homosexual in the KRG. This is due to the fact that while gay men could probably have the opportunity to escape, women have no means to do so. While gay men can deal with smugglers, women’s lives would be put in further danger if they were to take the risk of escaping the country. And this is why there are hardly any female members of the LGBT+ coming out. Those who are in Europe and the US are there with their families and that limits their ability to come out as family ties are strong and dishonouring the family is fatal. In an interview with BBC, Ashour says he had to escape the country due to his sexual orientation and since social norms work as legal instruments, there is no safety within the Iraqi or the Kurdish communities for any individual in the LGBT+ community.

The KRG has the potential to create a safe haven for individuals in the LGBT+ community. Unlike other countries in West Asia, Iraq and the KRG are one step ahead. There are no laws that need to be dislodged. Rather, what needs to happen now is a discourse on sexuality. Our society should not wait for another murder of a young woman, or an LGBT+ individual, before there is discussion on what can be done.

Darya Najim

Darya Najim is a master’s student at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University, Sweden. She is currently writing her masters’ thesis on the Kurdish women’s liberation movement in Rojava.