3,765 Total views, 1 Views today

By Fiona Crouch

I like art to challenge me, to make the hair on the back of my neck stand up as it compels me stop and think. Sinour’s work does this and more. When I first started to research her art to write this piece, I was reminded of elements of artists – Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon, Edvard Munch and Henri Matisse. Then I realised I was wrong. These are all great artists, but they are men. As a woman, Sinur’s work deserves to be analysed through a female lens. How can you truly understand the paradox of identifying as a woman – our vulnerability juxtaposed with great strength and resilience – unless it’s part of your lived experience? I believe this debate is central to Sinur’s creativity as she explores her identity and position in the world.

Sinur was born in 1986 in Mahabad in Eastern Kurdistan. To be able to grow as an artist and freely express herself, she decided to leave Iran, moving first to South Kurdistan for 5 years (Sulaymani and Erbil) and then to Istanbul, her current home. Sinur holds a degree in philosophy from University of Tabriz. The philosopher’s quest to understand what it means to be human, to be alive – our right not just to survive, but to thrive – radiates from her art. Through her work, Sinur plants her feet firmly on the ground and proudly asserts who she is as an individual, as a woman, as a Kurd, while still acknowledging the fragility and emotion that makes us human, that makes Sinur, her.

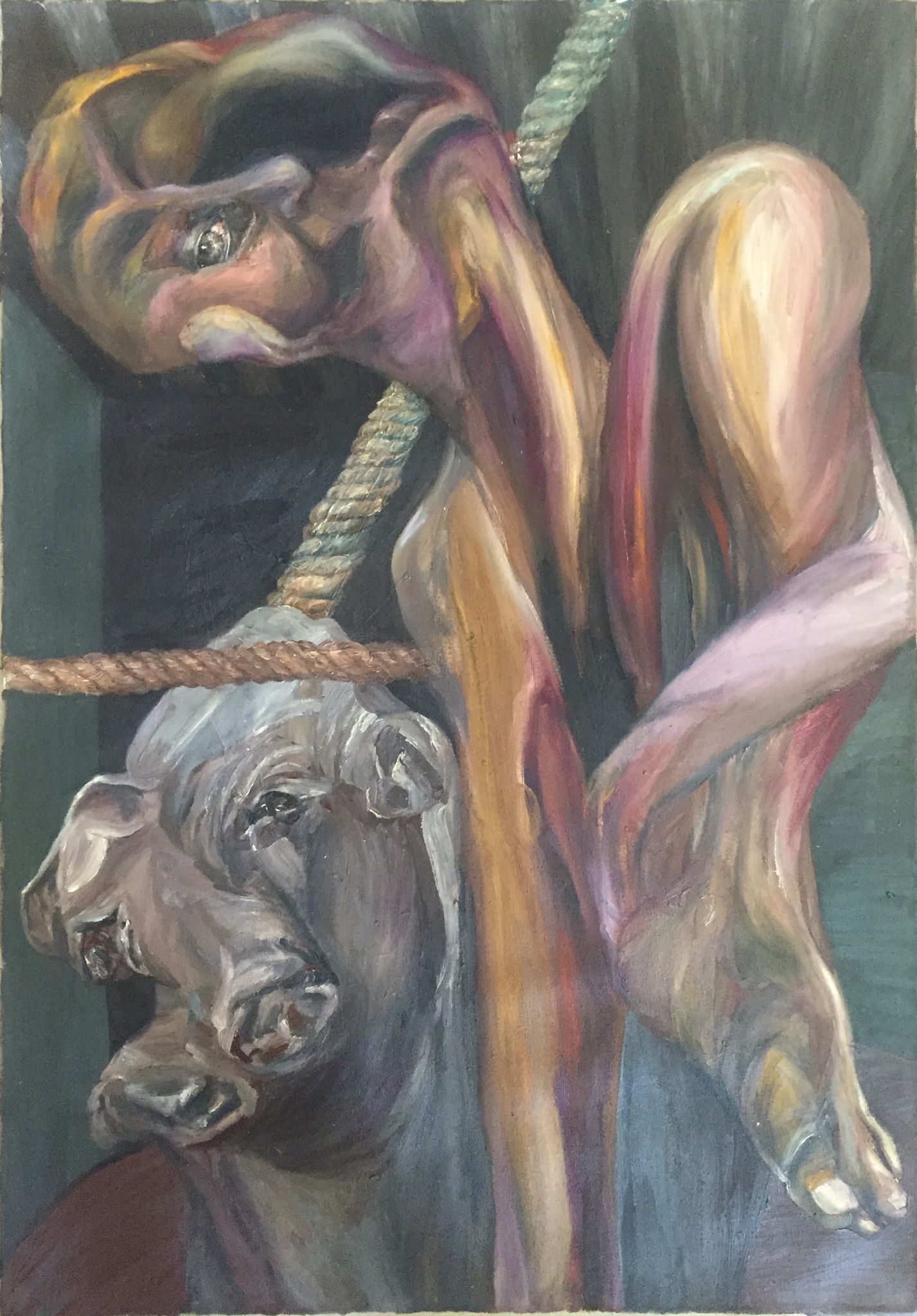

Yet, despite this clearly articulated presence, the appeal of Sinur’s work is not limited to female or Kurdish audiences; she is an artist for everyone. She paints with a verve that transcends these audiences – the detail is subtle but bold. Every time I look at her work I notice new details such as the piece where a beetle, a symbol of fertility, crawls up a naked woman’s leg as she is embraced by a naked male partner while being watched by eerie white figures in the background: an individual’s perspective and past, personal experiences will lead to very different interpretations. Her pieces celebrate artistic eclecticism the marriage of a range of styles in a single work – my favourite work is dominated by a figure sitting in a position reminiscent of Matisse’s Blue Nudes combined with the raw discomfort of a Bacon figure trapped in a geometric structure. Is this person a victim of conflict with an artificial limb or is the leg that dominates the front of the painting an artistic conceit that I’m over-analysing? Who does the shadow on the rear wall in the painting belong to? I’m draw back, time and again, to look at this figure with the contorted face. Each time I turn away with a different reading of the piece.

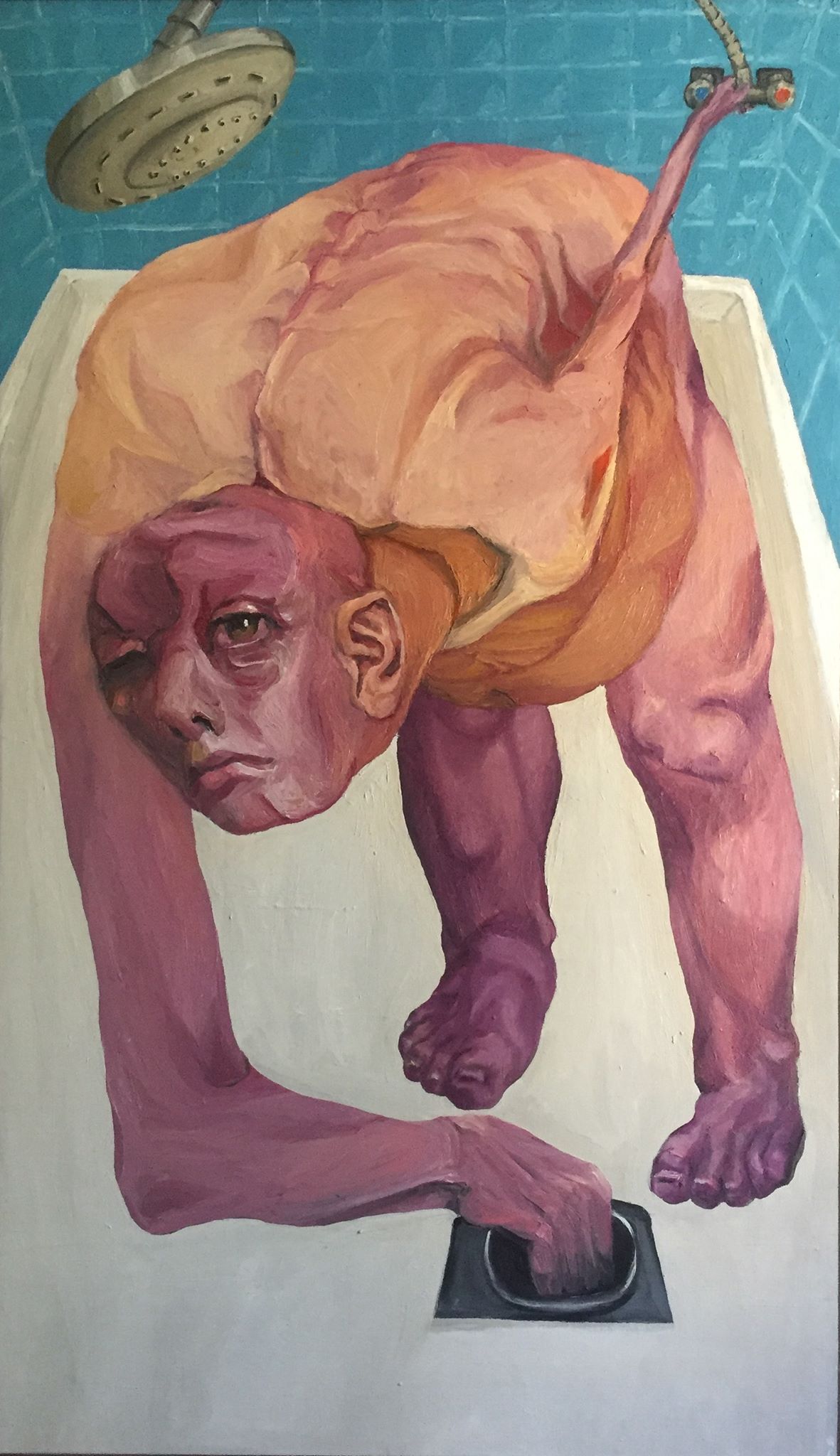

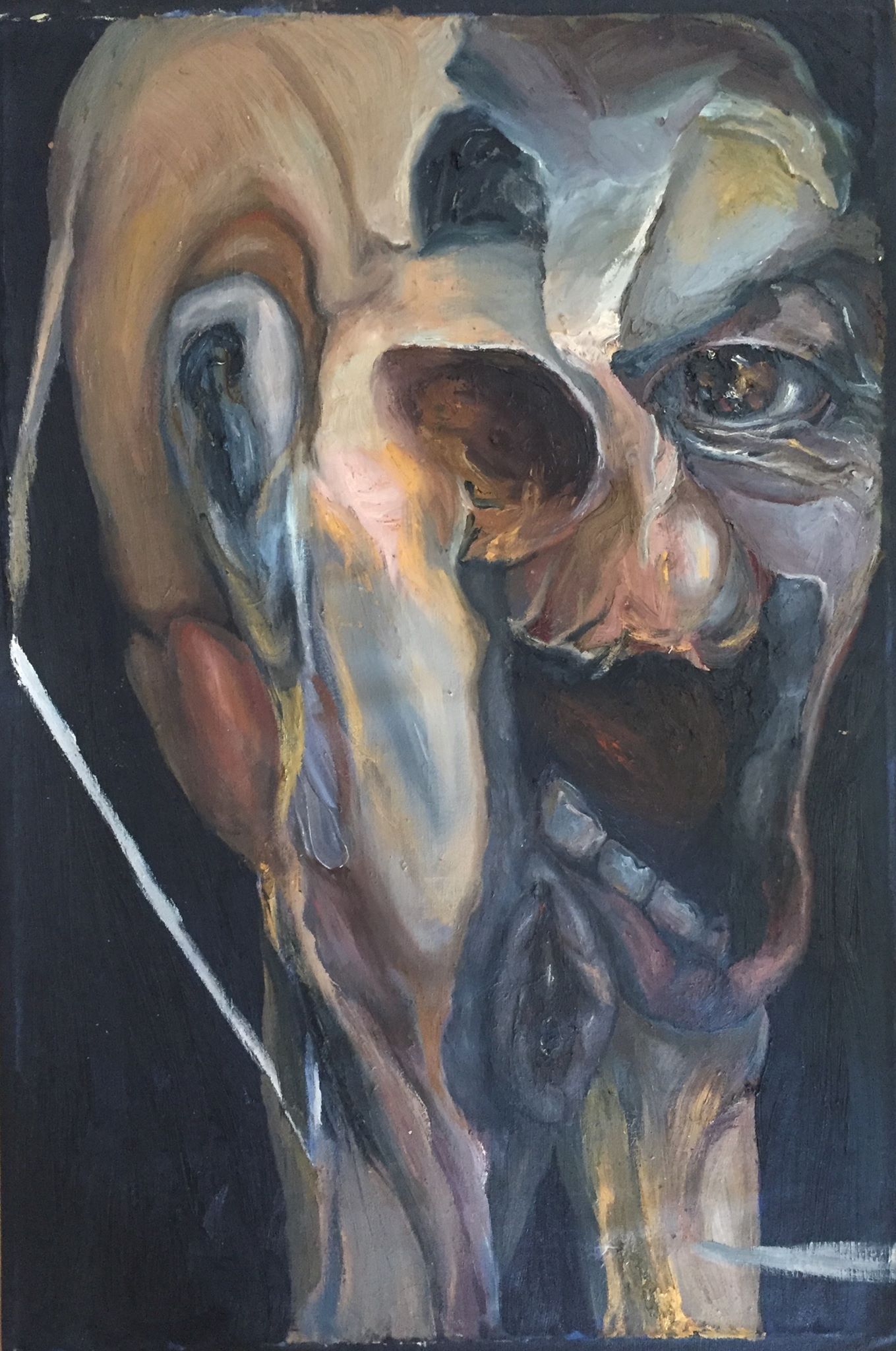

These human faces and figures dominate Sinur’s art, often self-portraits. There is sensuousness to her painting, figures entwined and female genitalia hidden in plain sight – but is this coupling consensual? These figures seem still, frozen in time against a fast-moving, blurred background that feels forbidding and threatening – at a macro level a metaphor of people in today’s frenzied world, but at a micro level representing how Sinur feels. It has long been said that eyes are the window to the soul. The eyes painted by Sinur mesmerise, staring straight at the observer. She has the same eyes that she paints in her work, and not just in the self-portraits that regularly feature make up her work: beautiful, deep and soulful, tinged with melancholy or pain but also defiant, hinting at an inner strength.

We are mortal. Sinur’s pieces often consider this theme – the white, ethereal but cadaverous figures that point to our limited time on earth. While they seem tormented, there is also innocence in the overlarge faces and hands that Sinour paints, a characteristic that is often found in children’s artwork. Her use of this technique works lending a playful air to her ghostly figures situated in the dark, forbidding backgrounds: sticking two fingers up and declaring that I’m here and I survived, despite what you’ve thrown at me. Their optimism for the future is suggested through touches of yellow and light.

And what are these figures trying to do? Deep red slashes or scratch marks are seen in a number of her pieces. Are they trying to escape or are they threatened by outside forces trying to get in to the canvas (in one painting a sinister, reptilian hand snakes towards the protagonist)? Highlighting these scratch marks, as well as lips and items of clothing, in red, the colour of blood, synonymous with childbirth, menstruation, war, pain and martyrdom, underscores both Sinour’s focus on her identity as a Kurd and a woman. The use of this colour always brings to mind the execution of Mary Queen of Scots who, according to legend, wore a red petticoat to her death in 1587. The reasons can only be conjectured but are likely to have included sartorially announcing her regal birthright, signalling her martyrdom and faith, but perhaps also an intimation of protofeminism. Throughout her work, Sinour’s use of colour is striking, whether it is monochrome, dark hues of grey and brown or vibrant pink, green, blue or yellow. It keeps the viewer on their toes, unable to settle into a pattern of expectation. I like the impact: for me, it encapsulates the complexity of being human. This is the essence of Sinur’s art, the many facets of her individuality, of our individuality. Her paintings proclaim, “I am Sinour. I am human. I am a woman. I am Kurdish. I am all of these things and I am proud”.