4,848 Total views, 2 Views today

A review of ‘Documenting Darkness’, Osman Kader Ahmad’s exhibition at Esta Gallery, Sulaymaniyah, 18/12/2019 – 18/02/2020.

By Hishyar Abid

5/1/2020

Not many survived the dreadful Anfal genocide. Among them, only few have managed to share their experiences with us. Fewer still have managed to document those experiences. Therefore, we must cherish the fact that one of those who were witnesses to the event, Osman Kader Ahmad, not only managed to find a way to document it but did so in an artistic form. This artist developed a unique platform to depict the situations and capture the fear of the victims as they were led to certain death. Over the years, Osman has deciphered and reconstructed these events from his personal memories of them as well as his vast research and interviews with survivors, who displayed admirable resilience and whose experience he also captured.

The difference between his own experiences and those of others is imperceptible. This is because he has not set out to register his own experience, nor those of anyone else for that matter. There is nothing denoting the personal in his drawings. He is simply a witness, recounting those experiences with full ownership of every line but without linking any of it to himself. He could have inserted his personal experiences, and the effect would likely still have been admirable. But what he aims for, instead, is brutal objectivity that pierces through the lines and the medium and demands to be recognised.

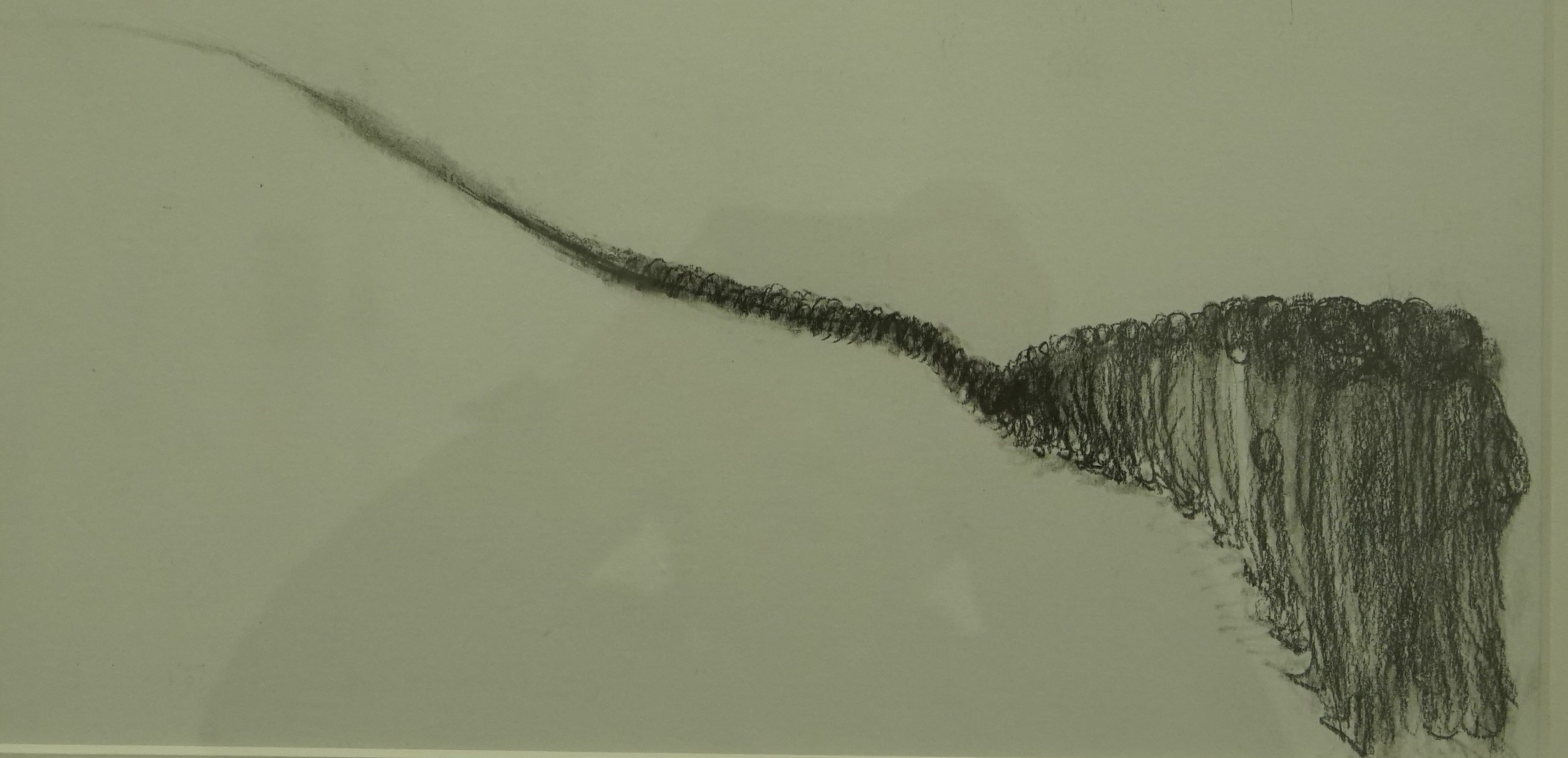

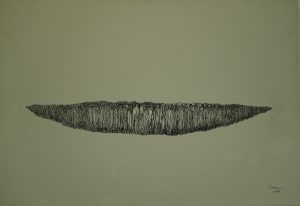

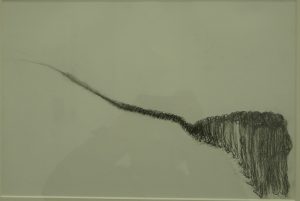

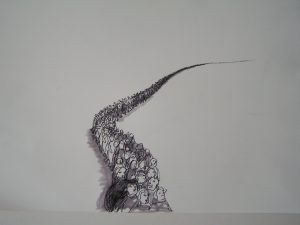

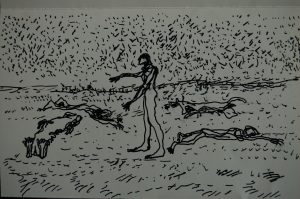

The drawings are varied in shape, size and even medium, but they are consistent in style and substance. The style is a simple form of drawing that approaches the raw abstract. The form is even simpler. Anyone can do it. There are many lines and no colours. The figures are mostly ant-shape or matchstick shaped with joint-in lines. The lines link the figures in a continuum that goes on forever and then transmogrifies into the outline of a mountain or some other landscape, or narrows down from the middle to both sides to form a smile-like shape. The faces are all rough sketches that are closer to those found in graphic novels rather than portraits, and yet they are each expressive and very much alive.

To me, this is the mark of great artwork— to be faced with a piece of artwork that leads you to think you too could have done it. That is what makes this work stands out. It is stark in its simplicity, so accessible that anyone could relate to it, yet it is so powerful and fresh that you can’t think of any parallels. The subject matter is equally mesmerising. The wave of bodies in motion, at the foreground, which flows into one line that disappears in the distance, sometimes into oblivion, other times into the landscape. The continuity between the bodies and the background, often represented by a single uninterrupted line that joins them all signifies the unity between man and nature. The crimes were not committed against humanity only, but against nature too. The fear, mixed with puzzling determination on the faces of the subjects as they march on speaks volumes for the silent victims. As Sarah Parill, the London-based senior book designer and artist, said about Osman’s work: “There is silence in the scream. It is unspeakable.”

The industrial scale of the killing machine, represented by the massive military fortresses that gulp them all before sending them off to their slaughter, as well as the massive lorries, the helicopters and the faceless soldiers, is visible and tangible.

However, none of that trumps the personal element of the victims, represented by the faces of the figures in the foreground, as well as a series of portraits of women, beautiful women, in spite of their attempts to uglify themselves, presumably, to escape the attention of the officers who pick them for their hour of fun. The mother, bending over her child for protection when her face clearly emits fear, is another example.  Osman’s work represents a major effort into constructing a national memory of the Anfal genocide, something that has been sorely lacking in the paltry offerings of the Kurdistan Regional Government, which has been saving for the Halabja Memorial and a few other flimsy initiatives. Least of all is the ill-founded Anfal Memorial Foundation that has so far swallowed millions of US Dollars with very little to show for it. National Memory, which is the sum of the experiences and cultural products that are shared by a whole nation, cannot be confined to individual initiatives or sporadic half-fulfilled projects. National Memory is instead a shared interpretation of a country’s past that combines commemorative ceremonies, monuments, myths and objects that all require a consistent approach engendered by the whole national establishment.

Osman’s work represents a major effort into constructing a national memory of the Anfal genocide, something that has been sorely lacking in the paltry offerings of the Kurdistan Regional Government, which has been saving for the Halabja Memorial and a few other flimsy initiatives. Least of all is the ill-founded Anfal Memorial Foundation that has so far swallowed millions of US Dollars with very little to show for it. National Memory, which is the sum of the experiences and cultural products that are shared by a whole nation, cannot be confined to individual initiatives or sporadic half-fulfilled projects. National Memory is instead a shared interpretation of a country’s past that combines commemorative ceremonies, monuments, myths and objects that all require a consistent approach engendered by the whole national establishment.

The Anfal was not just a crime committed by a ruthless regime in the eighties as revenge for the Kurds’ indifference to their invasion of Iran and the subsequent eight year-long war. It is a crime that is committed everyday, repeatedly, against the victims, the survivors, their relatives and the nation as a whole. The continued denial of it and the ambiguity over the number of victims is a testimony to that. This artwork and the exhibition itself go right to the heart of the construction of this collective memory and the national narrative that explains why the Kurds, at least in Iraq, wish to break free from the possibility of another genocide. The continued denial reveals a tacit readiness on behalf of the ruling elite to commit these crimes again, and only by remembering them and pursuing justice for the victims can the nation build a deterrent against its recurrence in the future.  This was the purpose that motivated the curator, Daro, who arranged for the exhibition. To walk by the drawings and decipher their meanings is one thing; to walk through these exhibits and transcend from one section into the next is another. There is an over-arching theme in the arrangement that collects the exhibits and puts a new narrative to them that is not available in the drawings individually. The sections reveal different aspects of the events, and each one tells the audience about one aspect: the personal element, the industrial element, the human scale and so on. The different sections build the whole narrative into one single message. There is also the painting in the middle of the exhibition that started off as a blank canvass, only to be drawn day by day by the artists, with the intention of finishing it off on the final day. This is not just the past that we are viewing, it is the present as it unfolds. It is a fulfilling walk into memory lane, one that leaves the observer with a great deal to digest.

This was the purpose that motivated the curator, Daro, who arranged for the exhibition. To walk by the drawings and decipher their meanings is one thing; to walk through these exhibits and transcend from one section into the next is another. There is an over-arching theme in the arrangement that collects the exhibits and puts a new narrative to them that is not available in the drawings individually. The sections reveal different aspects of the events, and each one tells the audience about one aspect: the personal element, the industrial element, the human scale and so on. The different sections build the whole narrative into one single message. There is also the painting in the middle of the exhibition that started off as a blank canvass, only to be drawn day by day by the artists, with the intention of finishing it off on the final day. This is not just the past that we are viewing, it is the present as it unfolds. It is a fulfilling walk into memory lane, one that leaves the observer with a great deal to digest.

Esta Gallery has established itself as a pioneering gallery in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. This is the fourth groundbreaking exhibition to be held at the gallery since its opening in January 2019. The previous exhibitions were for artists, such as Sufian Jalal and photographer Halo Lano’s, who have both produced ground breaking work but have not been recognised in the artistic scene in the ‘Culture Capital’ of Iraqi Kurdistan. Walking through this gallery reminds me of the great recycling feat that the Tate Gallery has achieved with its transformation of the station on the banks of the Thames in London into what it is today, the world-renowned Tate Modern. It has all the ingredients of a great venue, combined with the reassuring history of the place. This is a venue to watch.