3,786 Total views, 3 Views today

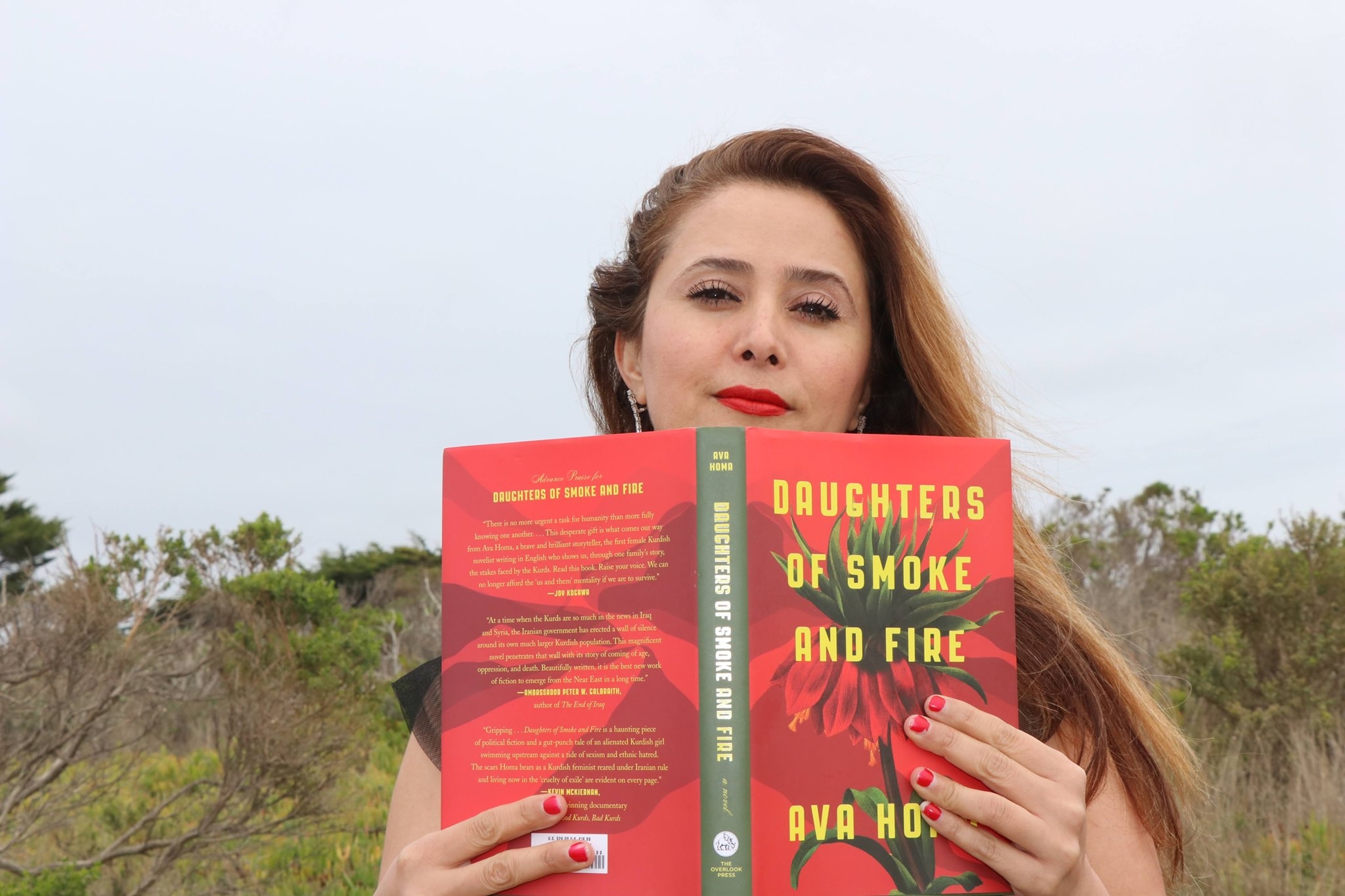

A review of Daughters of Smoke and Fire – a novel by Ava Homa

By, Shler Murdochy

Daughters of Smoke and Fire is an honest and powerful piece of literature that makes you not only cry but weep and yet it keeps you turning the pages as it’s laden with surpriseful events. Fiction is delicately and sensitively woven into the facts. The storylines and the characters’ strength stamps on one’s memory forever.

The characters are in a circle bound by the rules of that massive prison called Iran. No matter how hard they try, they can’t step out of the boundary of that same circle to lead a normal life. There is no way out, everyone whether (smart, hardworking, clumsy or stupid) is still destined to the same gloomy fate. They are betrayed by knowledge, religion, politics, by the so-called free media and so on. Some of them are outspoken and influential figures in the community, like Chia for instance. However, because he is from an underrepresented minority, his voice is neglected by the international community and the media.

The media outlets’ lack of interest comes to Leila, the protagonist of the story, as a shock and a reason to hold herself responsible for the fate of other characters. She doesn’t know how selective the main media is, especially when it comes to minorities and stateless nations, like the Kurds, perhaps the most misrepresented, mistreated nation on earth, considering the size of their land and population.

A conversation between Leila and Chia’s friend Karo confirms the truth of what has been said above:

“Chia was somebody to begin with and he became a bigger and bigger threat. I am not saying… You did the best you could under the circumstances, but the support, it was small… If the Guardian or the New York Times had written about him, Iran would have modified their charges, but only the Kurdish media outlets and a few Persian ones mentioned him. Even PEN and Unicef have limited reach, and he had too many admirers. It terrified the state that he was becoming an icon.”

Western politics seems to have very little, if any, interest in such nations unless they are needed for a specific mission, that is, to fight an evil force like ISIS, and then left alone to face death at the hands of authoritarian states in the region. This has been happening repeatedly throughout history time and again.

The world of this novel belies the knowledge you learn throughout your life, if you work hard and be persistent you can be anything and get anywhere you want in life. However, maybe not if you are a citizen of certain countries and, definitely, not a Kurd and live in the land supposed to be yours. Characters try their best but are continuously let down by the education system, the government and even by their own families. Leila for instance seeks escape to a better life through education and studying hard. However, she is stuck in the same spot and falls into one disappointment after another.

Chia and Shler, with their activism and youthful energy, try to establish justice and change the world to a better place and yet all they find is pain and destruction. Alan, some years before them when he was young, studied up to a PhD with the vision to help the same cause. Not only were his dreams and belief in change shattered forever under the prison torture and endless tragic events, but he struggles to even make a living. He sells little goods on the streets, he even steals in order to survive.

People inherit imprisonment and torture from their parents and grandparents. This vicious cycle of life repeats not due to any misconduct by the characters to harm anyone, but it happens for speaking the truth. Chia inherits prison from his father and Shler was even born in prison, from parents who were both in prison for political reasons. Homa thought of such beautiful little details like how Shler, as a baby, was treated in prison to create moments of relief in those difficult situations.

Powerful substories of minor characters to demonstrate Leila’s storytelling ability and to provide the reader with a better taste of what it is like to live under such tyranny. For instance, the Arab woman’s story, gives the realisation how that land, like many other lands nowadays, is full of injured souls and broken hearts. Hearts that are oppressed by God before humans. Hearts that have 100 different cuts from the knives of poverty, displacement, injustice and so on.

There is beautiful imagery and use of symbols in the novel. Rain and thunderstorm to resemble Leila’s anger and fearlessness, who stood at a gunpoint earlier that day. The appearance of a rainbow to show clarity of thought after fear and confusion of thought to “shift her focus on playing her hand the best she can” to save her brother.

After the business lounge incident in the airport, Leila starts to feel the pressure. She has to get herself ready for more exclusions and embarrassing situations that awaits her abroad. It is common for people who move places to experience discomfort, racism, bullying or other unpleasant experiences from the new society. But she doesn’t know that she has to be prepared for an extra portion of discrimination from the people, who are supposed to support her. From the people who are refugees themselves, like Karo’s mother and her Persian friends. People with chauvinistic mentality try to be superior, even in exile in a country that is neither Leila’s nor them.

“Not even one decorative bookshelf” in Karo’s parental home. Not many great readers are as wealthy. This is where two different worlds coming from the same place clash. Having suffered, to some extent, the same socio-political problems and fled the oppression of the same oppressive regime, yet they have completely different lifestyles and each at the end of two spectrums. The two are separated by the paths they choose. The path of reason and fighting for others selflessly or the path of Karo’s family who might have been able to have the same life, if they stayed in Iran, except for some personal freedom.

Several Interesting comparisons and differences between life in Iran, which in a way represents life in some other parts of the Middle East, in terms of culture, religion and the political system, and life in Canada or the west, in general. Comparison between how Leila panics about wearing a swimsuit in front of a public that includes men, but not to panic when a gun is pointed at her head.

In the cultures where females have been sent home and so used and abused at home, they have long forgotten about that direct contact with nature. For instance, swimming or sunbathing while their skin is uncovered and exposed. It isn’t allowable unless they are in their private spaces, or in only-women allowable places. But standing at a gun point is considered a daily life encounter, in the societies fallen in the potholes of religion and politics in the Middle East.

The comparison between the way nature is used and enjoyed by everyone in a normal society. People can dress and relax on the seaside as they please. In Iran, people are too controlled by the laws of religion to even enjoy nature freely and equally.

Leila is surprised to see a woman laugh louder than the permissible or the appropriate sound level for women when her partner bits her finger. In Leila’s previous world every aspect of women’s life was controlled, not only what they wear or what they eat and drink, but even how they talk or laugh in public. These are regulated by the morality police and by the eyes of the public who are more merciless than the morality police. Women will be the centre of suspicion if they travel long distances alone, without a religiously permissible male companion, particularly to a derelict area.

Hence, women are twice victims in a society so controlled by men and religion. Women have to endure the pain of deprivation of even such things as nature, whom they have been part of since time immemorial.

That deprivation from the direct contact with nature makes Leila ready to integrate into her new society from day one. She wants to try the food, to learn the language, to work and study, and to embrace nature with body and heart. She wears bright coloured clothes like green and yellow, the colour of the sun. An Islamic regime that is even against the colours God painted the world with, tries to cover the society with grey and black to drown everyone’s spirit and desire in the sea of bleakness. They try to make people live in preparation for death and graves from the day they were born.

Due to living under the rule of such a patriarchal regime and society, even those who have no political problems or financial difficulties, are suffering the same gloomy fate. They find salvation in either death or leaving the country like Fatima or Karo’s family for instance.

The last chapter is the readers’ pay off, after taking that long frightful journey with the author. Just to give the reader a moment of relief and to read unworried about another calamity that may befall the characters. The final part completes Leila’s character and frees her from the chains of culture, religion and society. It frees her from the fear of losing virginity, which is in the eyes of an Islamic state and society a crime that can result in death. She has no more fear of family or state rules and is not bound by the status of virginity. Breaking the cultural significance of virginity, which is considered the crown of honour not just for Leila but for her family and the wider community. Leila marries without the blessing of an older male guardian, which is also a crime that can result in death.

Leila develops from a house girl who cooked and cleaned after everyone, looked after by her brother and her boyfriend to a well-read person. She becomes an independent woman who works, becomes politically active and rises up to the challenges that face a politically active woman in such a dogmatic society. She stands up with brave ideas to save Chia from prison. Despite the harsh political, financial and societal reality, she flees home. She doesn’t accept going back to her previous life with her negligent parents. She endures living all by herself in Iran until she makes a radical decision.

Leila and Karo’s relationship contradicts the Islamic tradition that stresses “no man should be alone with a woman because Satan will be the third one present.” Leila and Karo spend time together in different locations. In different countries that have different laws in regard to men and women’s relationship. They stay under the same roof for several months all alone, far away from the terror of the Islamic republic’s laws and guards. They are far from the reach of the morality police, the legal guardian (for women), or any other sort of third eye that is on guard to observe them.

Despite being attracted to one another from the start and, at some point, having a marriage certificate, which is considered as a religious permission for a man and a woman to live under one roof and to satisfy their desires. They don’t touch one another until the time is right and they are both ready. Leila eventually grows out of the prude conservative girl to a fully rounded personality, who willingly embraces Karo’s love and relationship with heart and mind. By choice and understanding instead of societal pressure and obligation.

In conclusion reading this fabulous, important piece is haunting and yet extremely engaging and informative, especially since the horrific crimes of the Iranian regime make the headlines of the media outlets these days almost everyday.