3,796 Total views, 1 Views today

To Be Human Is To Be Creative

By Fiona Crouch

When I first started to research Narmin, I struggled to resolve the incongruity of the petite, smiling, brightly dressed woman juxtaposed against the darkness I feel emanating from her work. And then I read her biography.

An exploration of Narmin’s personal history reveals how her life has shaped her art following a childhood fraught with conflict and terror. Narmin Mustafa was born in 1980 in Tawela-Hawraman, a Kurdish region in Iraqi Kurdistan on the border with Iran. Her infancy was marked by the start of the Iran-Iraq War, when her family had to flee to the city of Sulaymaniyah, she was only a couple of months old. With Kurdistan being an area of significant conflict and fight against Iraqi government forces, in 1988 during the war’s latter stages, in an attempt to gain victory, Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi government launched the Halabja chemical attack, a genocidal massacre against Iraq’s Kurdish population. This remains the largest chemical weapons attack directed against a civilian-populated area in history. Narmin was eight years old when this happened, some of my clearest childhood memories occurred when I was this age. Imagine, just for a second – the sounds, the smells, the acrid taste of fear in your mouth – the irrevocable impact that this happening in your homeland would have on you and the people you love; the lasting mark it will leave on how you live your life.

Narmin’s work feels masculine, stamped indelibly with war. Yet, why have I created this delineation between the male and female spheres in my head? The bravery and professionalism of Kurdish female fighters are renowned – they are instruments, victors and victims in the warrior’s pas a deux as much as their male counterparts. Why does this gender bias linger in my interpretation of Narmin’s art? Put simply, gender for most women still preordains their destiny. At this point, I should declare that I am halfway through reading Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments. My mind is constantly drawing parallels between the fictional horrors of dystopian Gilead and the realities of Narmin’s childhood and the ongoing lived experiences of many Middle Eastern women today.

While I struggle to resolve my own issues of gender bias, it is inescapable that the central themes in Narmin’s artwork are war and trauma; the dark side of human existence. However, to be human is also to be creative. Creativity has been vital to our evolution; enabling us to flourish as a species, adapting and overcoming challenges. The use of creative activities as therapy, especially art, is well-established.

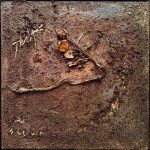

Narmin’s installations and paintings often feature mixtures of corroded bullets, iron, metal, black oil, coal, fabric, felt, and ammunitions. The process of finding, selecting or disregarding and then using the items in her creations is as important to Narmin as the finished piece. Her art is a cathartic process that she undertakes for us all, especially her fellow Halabja, and sequential wars survivors: sorting through items to be used in artwork is akin to sorting through and choosing to keep or disregard memories from your past.

She uses something that can bring death and turns into art, a product that commemorates, challenges but also brings joy. When a soldier goes to war, she dons her uniform, helmet and body armour to protect her. I noticed in photographs of Narmin working, she always wears the same black and white striped apron – her uniform – as she finds objects and allocates them a permanent place in her art. Her latest work features materials gathered from Shengal, an area where recent attacks and genocide by ISIS against the Yezidi population took place. Narmin used material – such as Peshmerga outfits, rubble, bullets – and added it to other war-related items from Kobane in Rojava to produce art. Indeed, location plays an important role in Narmin’s creative process. By combining objects from different sites – pieces recovered from abandoned city areas, the detritus of battlegrounds, dumped remains of mechanical objects – and repurposing them into art, Narmin is bestowing upon them a new meaning in time and space. These concomitant processes of recycling and renewal have a profound place in her art production: turning left behind objects into meaningful art is central to the narrative underpinning her work. Narmin is crafting a positive ending for maligned and unwanted things: a metaphor for the people of her region.

While Narmin predominantly bases her art around manmade items she finds, her finished pieces have an earthiness to them. The metal, mechanical objects that she has chosen seem almost organic, returning to a state where they are decomposing to become part of the Earth once again (more pessimistically, this could also be interpreted as the disintegration of human civilisation). I prefer to see this as representing the limitations of humankind, the temporariness of our individual time on the planet. As Narmin simulates the Earth reclaiming her items, I feel optimistic; a sense of rebirth and hope that next time the world’s resources will be put to better use. While there will always be evil, the human spirit can also be beautiful and strong. My mantra is to look to the light provided by creativity – using dance, music, acting, reading, writing, drawing – to find joy and meaning. Through her art, Narmin shows us that it is possible to vanquish evil and darkness; to remember the past while living in the now and looking to the future.