412 Total views, 107 Views today

By Shajwan Fatah

Above all, this article is inspired by the recent national and political struggles in Western Kurdistan (Rojava). The aim of this essay is to examine a feminine, yet profoundly feminist, element of Women’s Self-Defense Units (YPJ): their braids (kezî). This group of Kurdish women developed out of early Kurdish self-defense efforts that emerged in response to Ba’ath regime violence, particularly following the killing of 32 Kurds during the Qamishlo football match in 2004. These localized armed groups, which included women, later evolved into the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in 2011. Although women initially faced patriarchal resistance within the organization, their active participation in combat, especially against the al-Nusra Front in 2012, demonstrated their military competence. This experience led to broader recognition of women fighters and the formation of the first all-female battalions in 2013 across Afrin, Qamishlo, and Kobane, consolidating women’s role in the Rojava revolution.

Hair braiding, on the other hand, the roots can be traced back to ancient African societies, where it emerged as an early cultural practice. Scholars widely regard cornrows as the earliest known form of braiding. Archaeological evidence supporting this view includes a rock painting discovered in the Sahara Desert by a French ethnologist and his research team in the 1950s. The image, which depicts a woman wearing cornrows, has been dated to approximately 3500 BCE, making it the oldest recorded visual representation of braided hair. By around 3100 BCE, during the rise of ancient Egyptian civilization, hair braiding had developed into an elaborate and highly symbolic practice. The Egyptians were renowned for their intricate braided hairstyles, which functioned as markers of cultural identity and social status. Braiding was not merely decorative; it was also imbued with spiritual meaning, as braided hair was believed to protect the wearer from evil forces and to attract good fortune. Members of the upper classes, both men and women, often adorned their braids with beads, gemstones, and threads of gold. Among the most iconic figures associated with braided hairstyles was Cleopatra, whose carefully styled braids became emblematic of royal power and aesthetic sophistication, influencing beauty practices for generations. In ancient Greece, braided hairstyles functioned not only as aesthetic expressions but also as indicators of social status and occupation. Women’s braided styles varied according to class, with complex and carefully arranged updos typically associated with aristocratic women, while simpler braiding patterns were common among the working classes. These styles were often modeled on the idealized representations of Greek goddesses such as Athena and Hera, whose depictions established enduring standards of beauty and femininity. Within Kurdish traditions, this concept seems to be depicted in the myths such as the story of Shahmaran (figure 1), which regarded as the queen of serpents and is commonly portrayed as a wise and benevolent female figure, possessing a woman’s form above the waist and a serpent’s body below. She is believed to rule over snakes, and upon her death, her spirit is said to be inherited by her daughter.

The figure of Shahmaran is often seen as a symbol of wisdom, healing, fertility, and protection. Thus, it’s fair to state that in Kurdish culture, women often wear intricately braided hairstyles accompanied by traditional attire, particularly during the New Year celebration of Newroz. These braids carry significance far beyond aesthetic appeal, embodying strength, resilience, and the enduring spirit of Kurdish identity.

The Kurdish artist, Sahar Tarighi, states that decades ago, women would cut their braids at the graves of loved ones as a symbolic gesture to ensure the deceased would be remembered. In 2022, this practice gained renewed international relevance, as individuals worldwide cut their hair in solidarity with women’s rights activism in Iran, demonstrating the braid’s continuing role as a medium of memory, resistance, and feminist expression. Braids function as a metaphor for unity, demonstrating how individual strands, when intertwined, create a strong and resilient whole. Through this imagery, she seeks to encourage viewers to acknowledge their shared humanity, surpassing divisions of language, culture, and geography. For Tarighi, the braids represent not only acts of resistance but also the enduring spirit of solidarity that connects people in the collective struggle for justice and freedom among all oppressed and marginalized communities.

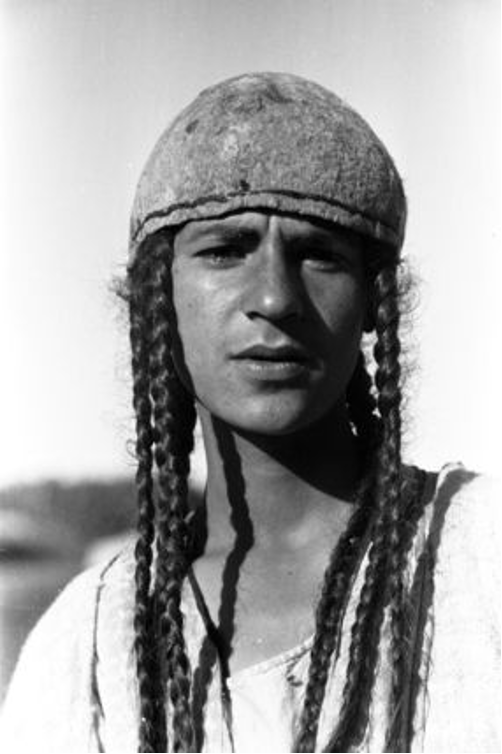

In addition to the myths, historically, Kurdish Yazidi’s hair braiding shows another side of the origins of this concept. Traditionally, and still practiced in the sacred region of Lalish, the growing of hair, beards, and mustaches, as well as the braiding of hair, formed part of customary life. Both women and men wore braided hair (figure 2), and mourning was marked by cutting one braid upon the death of a loved one. The mourning period was considered complete once the braid had grown back to its original length.

Philosophically, I want to add to the literature that women’s hair has long played a crucial role in defining or objectifying female identity, shaped by various religious, social, and cultural norms. Focusing on braided hairstyles among Kurdish women reveals not only a form of resistance but also a feminist assertion; that is to say, it seems like an embodied way of expressing voices against imposed doctrines and patriarchal structures (Butler 1990). Within the modern context, this Kurdish hair braiding seems to extend beyond cultural symbolism to contemporary social and environmental activism. A notable example is Keziyên Kesk (“Green Braids” in Kurmanji), one of the most prominent environmental organizations in North-East Syria. The group collaborates with the Autonomous Administration to advance social ecology initiatives, illustrating how braided imagery serves as a metaphor for interconnectedness, collective agency, and civic engagement in the region. While the organization’s primary spokesperson is male, it benefits from the active participation of many women volunteers. The organization’s name itself situates it within an eco-feminist framework, drawing on the cultural symbolism of braids in Kurdish society. In Kurdish folk tales and contemporary poetry, braids signify beauty, vitality, and abundance, while also representing female strength and courage (Hamelink et al. 2025). In other words, to investigate this Kurdish chosen style for women, particularly those who are members of the YPJ, seems to suggest a close reading. That is to say, the braids now signify not only a certain way of styling their hair, but they become a collection of mythical, historical, national, and gendered significations that represent complicated messages; messages that question power relations, class distinctions, and deconstruct the central themes of politics and socially manufactured ideologies among different communities. Throughout history, the subject of national identity has always been a riddle and unresolved, yet there are metaphors and ironies that implicitly seem to unravel it while also adding layers to the question of “Who are we?”

References

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Dillies, B. (2024, November 3). The enduring legend of Şamaran: Half‑woman, half‑snake, and keeper of wisdom in Kurdish folklore. Kurdistan24. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/story/809055/the-enduring-legend-of-%C5%9Famaran-half-woman-half-snake-and-keeper-of-wisdom-in-kurdish-folklore

Foucault, M. (1976/1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Holden, L. (2024, January 16). A history lesson on hair braiding. The Rinse – Odele Beauty. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://odelebeauty.com/blogs/the-rinse/history-of-hair-braiding?srsltid=AfmBOoqGueiruMubjDQT4GOavm2ojyakw6AtrGlnobQfCsJwTpYpspxy

Sechi Hair Academy. (2024, August 13). Global braids: Exploring the cultural history of hair braiding. Sechi Academy Blogs. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://www.sechiacademy.com.au/blogs/all-blogs/global-braids-exploring-the-historical-significance-of-hair-braiding-across-cultures?srsltid=AfmBOoq-_RPEQPc9C8MTxGqzNvk6o3GACN-sBfWCX6qdTkOugHCvtEtC

Skupiński, M. (2025). Women, environmental activism, and stateless citizenship in post-state North-East Syria. In Enacting citizenship: Kurdish women’s resilience, activism and creativity (pp. 71–101). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

The Braid Gallery 313. (n.d.). Braids in ancient civilizations. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://thebraidgallery313.com/f/braids-in-ancient-civilizations

Ursinus College. (2024, March 20). Inside Şamaran شاماران with Sahar Tarighi. Ursinus College News. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://www.ursinus.edu/live/news/8343-inside-amaran-with-sahar-tarighi

Yezidis International. (n.d.). Religion. Retrieved January 24, 2026, from https://www.yezidisinternational.org/abouttheyezidipeople/religion

YPJ Information & Documentation Office. (2023, June). Ten years of YPJ: The history and role of the Women’s Defense Units in North and East Syria and beyond [Brochure]. Women Defend Rojava. https://womendefendrojava.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Ten-Years-of-YPJ4_compressed.pdf