3,478 Total views, 1 Views today

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story,”

By Avan Omar

The statement above was made by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in the publication that accompanied the photography exhibition Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers. Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, which was held in Amsterdam at the Mozaiek in 2016, was an exhibition curated by photographer Negin Zendegani. It displayed both Zendagani’s portraiture and promoted her specific viewpoint as a non-Western European immigrant in the Netherlands. In the above statement, the author emphasises that stereotypes only provide us with fragmentary views of people. This metaphor of the incomplete fragment provided the core, structural idea for the exhibition as a whole.

In English, the title Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers roughly translates to “Fortune Seekers, Fortune Bringers”. Its meaning relies on a play on words. On the one hand, “Fortune Seeker” has a pejorative connotation, used to refer to people who leave their home in order to find luck in another place. Such people are often treated as “unknowns” and their motives are regarded with suspicion. However, on the other hand, “Fortune Bringer” conveys the idea that those who arrive in a new place can also bring good luck. In the exhibition, Zendegani draws our attention to the fact that socially accepted modes of behaviour form groups in specific ways – such as ways of thinking and acting – and that these in turn form the basis for a cultural identity, grounded in politics, language, ethics and culture. These varied influences determine the relations between individuals, but they also serve to define those who do not belong to a given milieu. For the subjects of the photographic exhibition, one of the central aims was to be seen as individuals with different roles, jobs and personalities.

Recently, this technique of presenting portraits of non-Western European immigrants and/or refugees has recurred in a number of visual art exhibitions. Some of these relate to the contemporary refugee crises, such as the ongoing project in Basel, Switzerland (2016–present) titled “ImPORTRAITS”. This project presents portraits of refugees with their most prized possession. Each portrait is accompanied by a short story in which the subject gives an account of him or herself and their relationship to the object with which they are depicted. Another such exhibition was a part of the ArtEZ Studium Generale in Rozet in Arnhem, the Netherlands (February 2016), and presented photos of refugees scaled to various sizes, with the purpose of giving an alternative view of refugee representation.

The entrance to Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers was dominated by large, high quality photographs of different people. The positions these people assumed in their respective photos were chosen by the photographer, who staged the shots with the intention of presenting her subjects in postures she felt were empowering. Here the concept proves to be more important than the aesthetics. As mentioned before, Zendegani’s was just one of many shows that discussed immigrant issues by means of portraiture. As is typical of these shows, her work is intended to communicate that the subjects of the portraits are not just immigrants, but are in fact individuals with personalities. I would like, however, to take a closer look into this trend of using the portrait as a medium to explore the contemporary refugee crisis. What is the function of the portrait, and how does it represent subjectivity? I pose these questions both generally, in relation to this broader trend, and also in relation to the specific case of Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers. To what extent did these exhibitions achieve their goal of challenging stereotypes?

Representing Subjectivity

Generally, a “portrait” is understood to refer to a likeness and/or representation of a particular individual. In the representation of its subject, the portrait has had a variety of functions and has assumed a number of different modes. Artists sought not only to depict the body as a material form, but also as a form that could suggest the sitter’s biography, character and sensibilities.

Historically, portraits have often been devoted to the bourgeois and aristocratic classes, the powerful and/or the dominant. In Western Europe, from the fifteenth century onwards – and responding to various artistic and social needs – artists began to depict themselves and their subjects in different ways. From the nineteenth century onwards, their motivations included the desire to challenge the portrait as a mode of historical representation, especially its connection to people in positions of power. Central to this was the portrayal of authority, accomplished both by aesthetic techniques and the bodily poses of the sitter. Through the portrait, artists have explored social roles and relations between individuality and cultural, class, sexual and gender-based stereotypes.

More recently, portraiture has been challenged by means of the newer medium of photography, while in the post-World War II period, portraiture has become especially associated with the exploration of identity. This development has culminated with postmodernism. Feminist theories have been central to this transformation, and have criticised the assumptions of traditional portraiture for its insistence on stability, integrative identity, and the self as an organizing agent of human behavior. They have argued for the psychological inadequacy of these assumptions, stressing the cultural bias of gender identity, and they have introduced questions of ethnicity and belonging – of who can be said to belong to the dominant culture and who not. As Chris Weedon claims:

Identity and culture are key issues in the ‘post-colonial’, ‘post-modern’ West. A world in which the legacies of colonialism, including migration and the creation of diasporas, along with processes of globalisation have put taken-for-granted ideas of identity and belonging into question.

Thus, issues of personal identity, and of how identity has been understood, have become central considerations in a great number of artistic practices and this awakening of interest in identity often involves the exploration of the body in terms of age, gender, nationality, race and/or ethnicity. During the late twentieth century, one way in which these issues were explored was via a return to the form of mimetic portraiture, especially the mimesis of canonically famous artworks. In this context, the viewer is supposed to be able to identify the famous portrait as well as the new subversion of the iconic image, including the ironic embrace of traditional poses, expressions and settings.

Artists such as Andy Warhol appropriated images from the popular press to investigate the social and public aspects of subjectivity. The reproduction of popular images from mass-media created a “reproduction of reproduction”. Through repetition, the image acquired the power to challenge the mythical dimensions and connotations of the original work. Amongst the many examples of this strategy, a particularly prominent one is Andy Warhol’s famous portrait of Marilyn Monroe.

The artist Cindy Sherman can also be situated in this lineage, although her work took a different approach to Warhol’s, since, unlike Warhol, Sherman inserted herself into the canonical works that she mimicked. Sherman photographed herself in stereotypical roles, such as that of a female character in 1950s Hollywood films – an approach she used for her black and white photographs “Untitled Film Stills”. She often inserted herself as a figure in old master paintings in European art history, such as those depicting Madonna and Child. Through the stereotypical representation of mass media images of women, Sherman comments on the social construction of identity.

This helps us to situate Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, since we now see that the use of portraiture to challenge representations of race, class, gender and religion is a major preoccupation of the form as a whole. The examples above also help us to frame a broader debate on how late twentieth-century artists outside Western Europe and North America can harness the tools of portraiture in order to challenge stereotypical identity designations. One interesting example of a non-Western artist who has challenged the notion of the portrait by appropriating a historical masterpiece is the Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura.

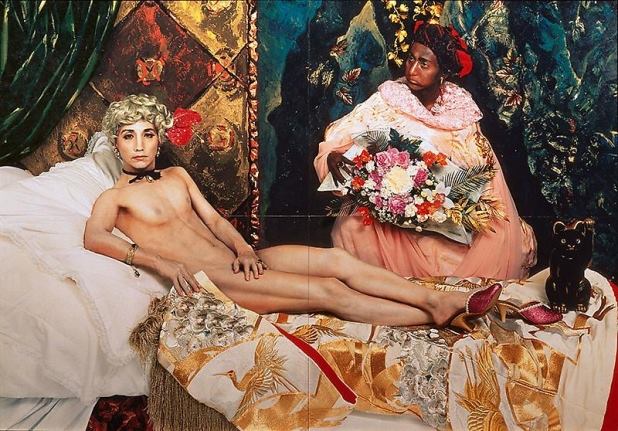

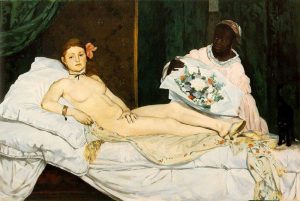

Morimura inserts his own likeness into iconic Western European works in order to confront issues of subjectivity and origination. In his work, Morimura embraces hybridity and creates spaces for alternative depictions of gender, race and ethnicity. He approaches the dimension of queer identity and drag by means of impersonation, and particularly by blurring the lines between male and female figures in canonical Western European paintings and photography. A specific example of this technique is his self-portrait Futago (1988).

By inserting himself in Manet’s Olympia (1863), Morimura challenges the portrayal of authority. Primarily he does this by playing with the poses of the original sitter. He enacts many alterations, changing the fabric pattern to a Japanese style and the cat to a Japanese toy. These alterations serve to establish a connection between different histories of commerce. At the same time, Morimura also explores the materials of commerce, and he connects these to the body by prostrating himself in the same position as the prostitute who originally posed for Manet. Moreover, Morimura impersonates a female sitter and, significantly, although he hides his male sexual organ, he does not try to disguise that he lacks breasts. Overall, these changes create a hybridity between cultures in a manner that further demonstrates the inequality between gaze, desire and position. Futago also plays with performative ethnic identity, especially through the juxtaposition of the unaltered black servant woman, interrogating the relationship between ethnicity and social hierarchies. Yasumasa Morimura, Cindy Sherman and Andy Warhol, amongst many others, are powerful examples of artists who return to famous portraits and artworks, and who use mimetic portraiture as a tool to help unpack notions of subjectivity, hierarchy and power relations.

In addition, several other artists have used the portrait and self-portrait as a performative arena in which objects and photographic techniques can be used to explore stereotypical structures of reference. In place of non-Western artists especially, these reference structures often concern outward appearances, such as hair, skin, dress and posture. There are many examples and we will have to restrict ourselves here to some of the best known. An instance of this: Glenn Ligon is an African-American, homosexual male artist who generally deals with race and sexuality through different mediums such as painting, photography, video and text. Accordingly, in his works Ligon has explored cultural and social identity with a particular focus on the ways in which American society is shaped by representations of the black body, slavery and sexual politics.

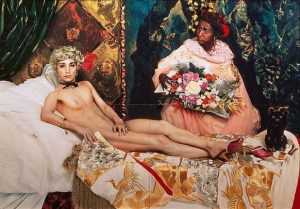

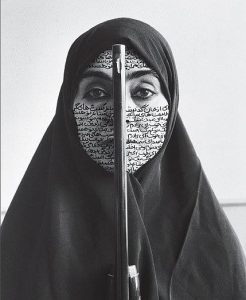

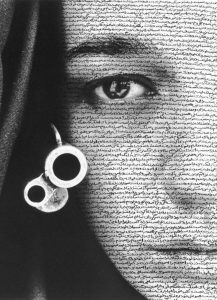

Shirin Neshat is an Iranian-born artist based in the United States. Her work responds to multifaceted identities and critiques of cultural hierarchy, and the resulting discrimination, that various social groups are made to suffer. Neshat claims that she has had to fight two different battles: one against Western images and perceptions of the political and religious identity of Middle Eastern people in general, and of Middle Eastern women in particular; and another battle against the regime and politics of Iran. Her photographic works use symbolic elements such as veils, guns, gazes and, very often, poetic text. Neshat uses these devices to represent and modify different body parts, such as faces, feet, hands and eyes. One example is the black and white “Women of Allah” series (1993–97).This focuses on the role of women in the 1979 (Islamic) revolution in Iran. Neshat frequently depicts body parts covered with Persian poetry, the text inscribed in black ink. These often turn into self-portraits. Below, Neshat poses in an outfit denoting a strict Islamic dress code juxtaposed provocatively with a gun, her gaze directed at the viewer.

Shirin Neshat,self portrait Women of Allah series,1993-1997

Shirin Neshat,self portrait Women of Allah series,1993-1997

Beside her exploration of women’s roles in the revolution and in Iranian society, Neshat points to the silencing of women. The texts that are inscribed onto her face, as well as the faces of other women, is female Persian poetry: the artist emphasises that women still have much to say. On the one hand, the act of looking at the viewer while holding a gun conveys strength; while, on the other, Neshat attempts to challenge the notion of the stereotypical image of Muslim and/or Middle Eastern women in Western Euro-American society.

The veil typically indicates the deprivation of sexual character; and yet the essential symbols of gaze, gun and text give an erotic power to Neshat’s women. These examples constitute some of the uses of photographic portraits used to challenge the notion of identity and to represent subjectivity within the framework of art. Confronting the portrait, especially in a gallery space, often brings about mixed feelings. The viewer can feel an association with the portrayed that is reinforced, or else counteracted, by common spatial and temporal signifiers. Shearer West asserts that:

Portraits are not just likenesses but works of art that engage with ideas of identity as they are perceived, represented, and understood in different times and places. ‘Identity’ can encompass the character, personality, social standing, relationships, profession, age, and gender of the portrait subject.

As West emphasizes, these qualities are not fixed, but depend on the expectations and circumstances of the time and place in which the portrait was made. To adapt the aforementioned strategies of challenging through portrait and information to Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, we can say that, in the time of immigrant/refugee crises and in the heart of the Netherlands, the participants and the photographer attempted to reveal the complexity of identity via photography. In these cases, the artist forgoes elaborate pictorial techniques in order to question the origins, the lineage and the audience for photographic representations as such.

Xiao Chun Zheng

Seamstress

The question is to what extent do these portraits provide a Dutch audience of Western European heritage with an alternative perspective? How can the subjects of the photographs use likeness – which is to say, the very means by which they are recognised as different by those in their host society to challenge the stereotypes through which their host society tends to interpret them?

In Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, Zendegani presented twenty-one portrait photographs. As we can see from the examples above, some of the portraits represent the individual in a way that reveals their profession. This inclusion within the portrait of various markers of the sitter’s profession is intended as a means of challenging stereotypes. One example is Figure 6, in which Xiao Chun Zheng is presented as a seamstress by means of her posture in the photo, by the inclusion of objects related to her work and by virtue of the direct eye contact she establishes with the viewer.

This may seem similar to the technique, a technique used by such artists as Shirin Neshet, of inserting symbolic items into the portrait’s frame. However, in contrast to Neshet, Zendegani’s photography does not always achieve its main aim. If we take as our examples Figures 8 and 5, it is clear that the works are much like a traditional portrait, in which the goal is to depict the likeness of the sitter. The photos do not provide any hints to indicate the struggle of the sitter and do not show the professional background of the persons portrayed.

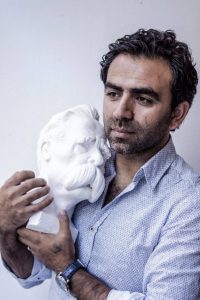

The problem becomes manifest as a tension between how non-Western European bodies in Dutch society feel represented and how they wish their host society would see them after, in many cases, twenty years or more. The sitters are posed awkwardly, holding props that seem to shout “see me in connection to my respected profession!” The man in Figure 7 is a philosopher, posing with a statue of Nietzsche. His use of a symbol evoking intellectualism within the Western European cultural heritage reveals a demand to be seen in this lineage. This act expresses a need that characterises the whole exhibition: the desire to be seen in a certain way, the desire to have a third space.

West speaks about the role of the representational portrait in relation to its social role by quoting Erwin Panofsky:

“A portrait aims by definition at two essentials … On the one hand it seeks to bring out whatever it is in which the sitter differs from the rest of humanity and would even differ from himself were he portrayed at a different moment or in a different situation; and this is what distinguishes a portrait from an ‘ideal’ figure or ‘type’. On the other hand, it seeks to bring out whatever the sitter has in common with the rest of humanity and what remains in him regardless of place and time.”

Panofsky pointed out that the distinguishing characteristic of a contemporary portrait, as opposed to a figure within a traditional painting or narrative, is that it attempts to show both the differences and likeness of the sitter, thus deviating from the historical portrait as a means of presenting an “ideal” figure or type. And yet, in many of Zendegani’s photographs, the likeness is visible but the difference is missing. In addition, in Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, my confusion as a viewer derives from my inability to see why the participants represented themselves as a group or type. This seemed to me like a peculiar way for them to assert their individuality.

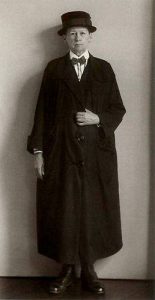

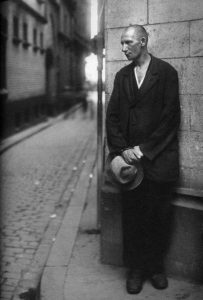

Historically, the photographic presentation of “Typology” functioned as a means to gather members of a certain type or class under the heading of specific categories. Zendegani gathers groups that share many of the same concerns, operate on the same social stages, and belong to the same social classes, at least from the perspective of the members of the (Dutch) host society. To compare this work with earlier photographic typologies, we might turn to August Sander’s 1929 series of portraits entitled Face of Our Time, which documented German society between the two world wars. Sander created a record of social types, classes and professions, but did not include names. He began with different types of occupations, starting with the farmer and then moving on to the unemployed.

Washerwoman, 1930

Real Estate Agent, 1928

Unemployed Man 1928

Overall, the series tried to show the hierarchical relationships between these categories. For Sander, the presentation of the portraits as a collection served to reveal much more than the individual images themselves. The display created a juxtaposition of images that reflected and exposed a hierarchy, but did not include any individual names.

Conversely, Zendegani includes a written description for each portrait, including the name of the sitter and their profession. I believe that in this case she has succeeded in conveying the aim of the exhibition, that is, to indicate that the photographs are not attempts to classify people according to group. However, the sitters’ aims were not fully conveyed by the photos themselves. As I mentioned above, the sitter of the portrait can only be shown by a depiction that aims at something more than mere likeness; passport-type photos such as Figure 8 will not suffice. This recognition is a precondition for work that wishes to challenge the viewer and the fixed representation of the sitter, such as that of Morimura and Neshat.

Self-portrait

Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers cannot be described as a self-portraiture exhibition in the traditional sense; rather it constitutes an entire oeuvre geared towards the kind of self-exploration that typically characterized the self-portraiture of the past. Every individual who participated in the exhibition did so in an attempt to represent themselves through self-portraiture. Their aim was to reveal the complexity of identity, to display a shared human constituency, and to create a collective platform for dialogue. Negin Zendegani attempted to accomplish this by photographing those who, like her, had faced similar struggles in Dutch society around the problem of integration.

In her article “Performing the Other as Self: Cindy Sherman and Laura Aguilar Pose the Subject”, art historian and critic Amelia Jones argues that “the self portrait photograph performs a kind of visual autobiography promising to deliver a particular ‘subject’ … to the viewer through a visual ‘text’ narrated in the first person”. What is striking in this statement is the assertion that the self-portrait takes the position of the person portrayed. Jones additionally claims that the self-portrait transmits a subject to the viewer. Overall, this argument can be seen as one that attempts to position self-portraiture as a means of illustrating, and relating the experience of, subjectivity.

In what follows, I will present a short interview that I undertook with one of the participants in Zendegani’s exhibition. In response to my question regarding his motivation for participating in the project, about why he wished to present himself by means of the portrait, and why his self-presentation through his work as a musician was not sufficient, he stated:

“When I am doing music it is evident, because people can hear it. It is very direct. Nevertheless, I think that the refugee is not present enough. But he also does not have enough space to present himself. So I took the opportunity to have a portrait of mine, because it gave me the possibility to create an alternative view, to show people that we actually have a goal. In that way we can convince people that we are very diverse and that there are many ways to see us. Because it was an answer for those people who were saying that the refugees are a danger. Every day in the media and on the TV, we were accused that we just came here for pleasure. We have a really bad reputation, like we are criminals, and have no desire and so on, we are seen as objects, while not everyone is the same … I want to participate and be seen in other ways. Sometimes when I walk in the street and I have my instrument (viola) with me, I feel like people are watching me and questioning me. “

The motive for participation in the exhibition, and more generally the desire to represent oneself by means of the portrait, can thus be seen in something like the terms established by Amelia Jones: the portrait provides its sitter with the possibility of performing their subjectivity for the viewer. The strategy of self-performance in self-portrait photography has a particular force for those who struggle to articulate themselves as subject rather than object. In the case of the interviewee, this can be seen as a kind of rejection of the fixed image that he feels exists of him within Dutch society: an image he feels leaves little space and creates little faith in his self-presentation as a professional musician.

This is echoed in the parallel publication to the exhibition, in which the portraits were accompanied by a short biography detailing the different educational backgrounds of those involved as well as their various professions. The interviewee believed that through his self-portrait he could create a new space. This hope of his is juxtaposed with the purported desire of the viewer to find meaning when encountering a photograph. The interviewee performs through the photograph and tries to send a message to the viewer.

Magazine Cover

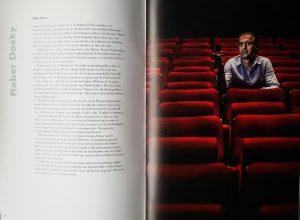

magazine cover Reber Dosky , Filmmaker

As critic Craig Owen states, “The subject poses as an object in order to be a subject”. The point here is about the construction of subjectivity with the gaze of the other in mind – a subjectivity premised on thinking that one knows the viewer.

By encountering a Western European host society such as the Netherlands, the illiterate, the artist, the doctor and the lawyer all fall under the same umbrella of “immigrant” and/or “refugee”.

This is part of the non-Western European immigrant’s confrontation with a fixed identity that is imposed on them. Arendt analyses the situation of the Jews during World War II in comparable terms. She deals with problems of identity and imposed identity via the figure of the Jew.

Arendt states:

“We fight like madmen for private existences with individual destinies, since we are afraid of becoming part of that miserable lot of schnorrers whom we, many of us former philanthropists, remember only too well. Just as once we failed to understand that the so-called schnorrer was a symbol of Jewish destiny and not a shlemihl, so today we don’t feel entitled to Jewish solidarity; we cannot realize that we by ourselves are not so much concerned as the whole Jewish people. Sometimes this lack of comprehension has been strongly supported by our protectors. Thus, I remember a director of a great charity concern in Paris who, whenever he received the card of a German-Jewish intellectual with the inevitable ‘Dr.’ on it, used to exclaim at the top of his voice, ‘Herrr Doktor, Herr Doktor, Herr Schnorrer, Herr Schnorrer!’”

The director made this explicit by stretching the “r”, which produced a ridiculous and comical effect. By mocking the doctor, and combining his mockery with repeated use of the epithet “Schnorrer”, the director committed a violent act. Arendt argues that, in this context, “being a doctor of philosophy no longer satisfied us”.

In relation to the exhibition Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, the image of the outsider did not change over time. The participant’s perspective, and the goal behind the exhibition, that of illustrating individual subjectivities, is repeated many times in the related materials. Nevertheless, I discovered that often this representation of difference is denied by others. In my interviews, it emerged that non-Western European immigrants are still often categorised under the same umbrella. Similarly to Arendt’s description of the episode in which the French man could not conceive of a person who is at once a “Jew”, a “doctor”, and an “object of charity”, the targets of stereotyping and discrimination in the exhibition tried to fight against fixed social classifications. Like Arendt’s figure of the Jew, their individuality, personality and profession are ignored or misrepresented. They are not recognised by their host society but are instead categorised as “outsiders”, whether they are an immigrant or a refugee.

In the exhibition Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, individuals belonging to different groups faced the same issues of group fixity. Stereotypes impede individual performance and the individual’s self-presentation in daily life. This generally results in unchosen categorisation. Nevertheless, the result of this exhibition, which tried to counter stereotypes, was ambiguous. I see Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers as an opportunity to unpack how stereotypes are visually signified even in the act that confronts them. In this discussion, it is important to highlight how the fixed image and/or stereotype is a site of both social construction and struggle over this construction.

I examined examples of the struggle over the social construction of identity that take place within the domain of the visual art exhibition. Specifically, I was interested in exploring why Zendegani’s exhibition was organised and in questioning what it revealed about the difficulty of escaping stereotyping and its associated social behaviours. As discussed by Homi K Bhabha:

“The stereotype is not a simplification because it is a false representation of a given reality. It is simplification because it is an arrested, fixated form of representation that, in denying the play of difference (that the negation through the other permits), constitutes a problem for the representation of the subject in significations of psychic and social relations.”

Bhabha states that through stereotypes, people are “denied the play of difference”. The non-Western European bodies that I described in this chapter were sometimes involuntarily grouped under fixed social categories, but sometimes they intentionally assumed these categories, as is the case in the exhibition, which as I mentioned above provoked conflicts or struggles around the question of social encounters and togetherness . Tension occurs because these difficulties reveal the extent to which stereotypes underlie reality.

List of Figures

Figure 1 Édouard Manet, Olympia 1863

Figure 2 Yasumasa Morimura, self portrait photographs Futago 1988

Figure 3 Shirin Neshat, self portraite, Women of Allah series,1993-1997

Figure 4 Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah series,1993-1997

Figure 5 Ali Authman, Composer. Negin Zendegani Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, 2016

Figure 6 Xiao Chun Zheng, Seamstress. Negin Zendegani Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, 2016

Figure 7 Ofran Badkhshani, Philosopher. Negin Zendegani Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers, 2016

Figure 8 Amino Ali Obead, Pharmaceutical assistant. Negin Zendegani Gelukzoekers, Geluk brengers, 2016

Figure 9 Washerwoman. August Sander Face Of Our Time, 1930

Figure 10 Real Estate Agent. August Sander Face Of Our Time ,1928

Figure 11 Unemployed Man. August Sander Face Of Our Time,1928

Figure 12 Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers’s magazine cover. Negin Zendegani, 2016

Figure 13 Reber Dosky, Filmmaker .Gelukzoekers, Gelukbrengers’s magazine pages. 2016