5,385 Total views, 2 Views today

By Fiona Crouch

I am currently reading Look Again, the autobiography of David Bailey, the legendary British photographer. He is part of a triumvirate of London-born photographers, nicknamed the Black Trinity, along with Terrance Donovan and Brian Duffy who revolutionised their industry. They were creative pioneers whose work captured the zeitgeist of 1960s London. All three grew up in the war-ravaged East End, learning to survive, and even find joy, among reality of conflict, as the horrors of war invaded the homes and hearths of British cities. Their formative years inspired their work. Why do I mention this?

For over a year I have been researching and writing about the artwork of Kurdish women. In some way, all these artists have been affected by Kurdistan’s ongoing political instability and violence; conflict has been the constant backdrop of their lives, terror a regular occurrence. Yet, all these female artists use these experiences as a source of creative inspiration, to make meaning of the madness they have seen. In Naz Hakim’s work, I sense a similar link between her personal experiences and her artwork that is apparent in the photography of the Black Trinity.

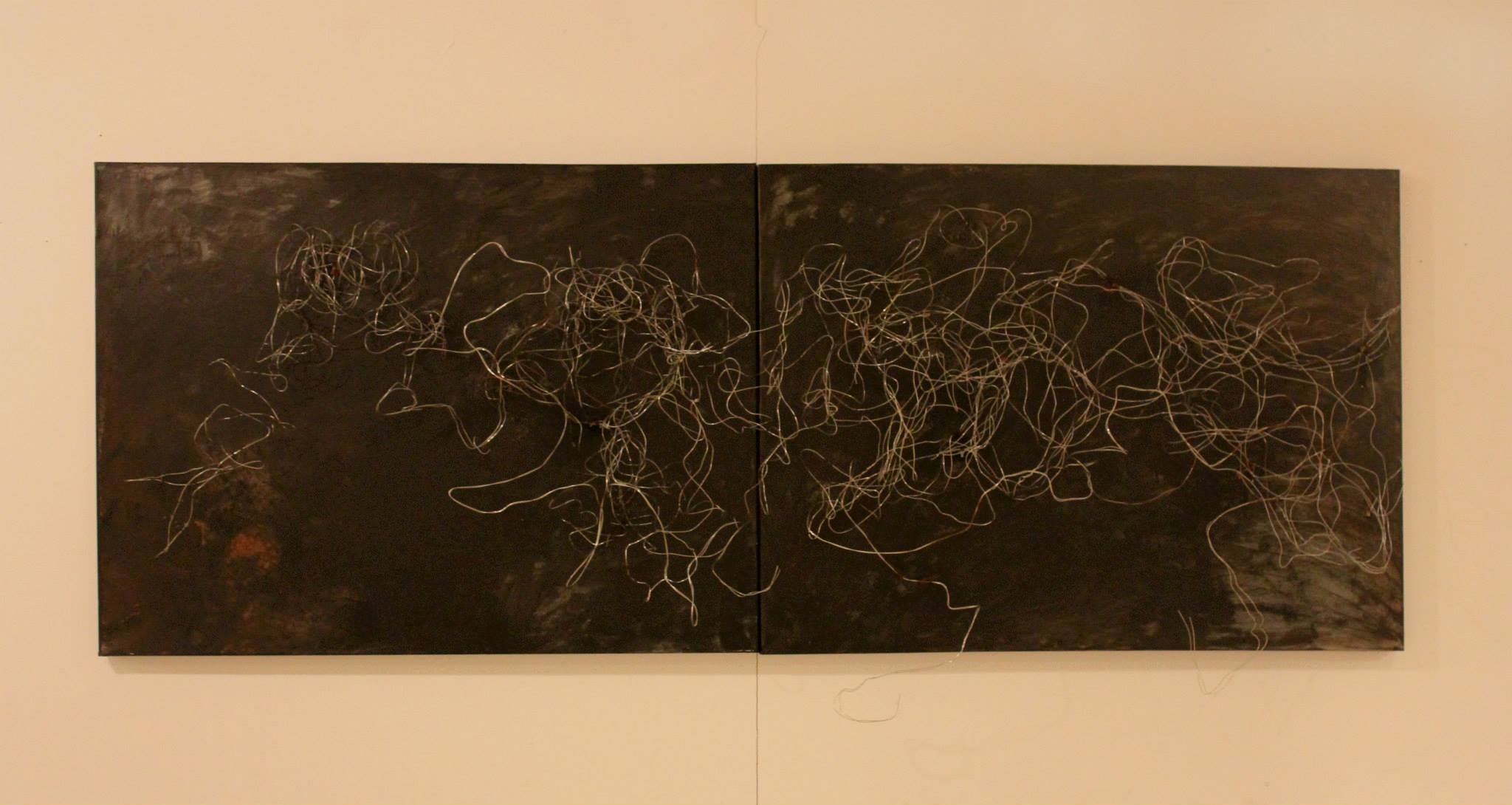

Naz was born in Sulaymaniyah in 1984 as the last phase of Iran-Iraq conflict began. The 1991 uprisings in Iraq and Kurdistan are likely to have been one of her earliest memories. In this month long period, it is estimated that across Iraq tens of thousands of people were killed and over two million people were displaced. In Sulaymaniyah, fighting was fierce: it was the first city to fall into the hands of the protestors and the last city to return to Iraqi government control before being recaptured by Kurdish rebels in July 1991. This kind of national trauma pervades the life of all its citizens, even if they are not directly impacted by what has happened; it leaves an indelible stain on the country’s psyche. I believe that experiencing this level of personal turmoil can boost emotional creativity: it can be motivational, resulting in an outpouring of originality as the mind seeks to understand and make meaning of the events. Naz expresses herself in a variety of media, including installation, video, painting and drawing. Her work is not pretty; it is bleak but thought-provoking. The dark, austere tones that are often combined with leftover or abandoned industrial objects are aesthetically unsettling, even jarring. She dares her audience to think.

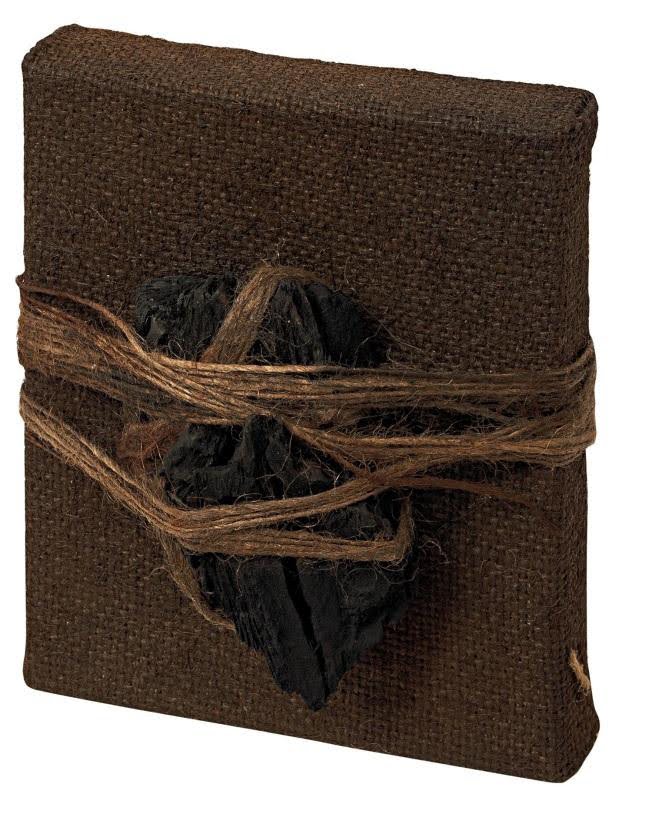

In post-World War Two London, the Black Trinity photographers used technological advances that were often prompted due to wartime innovation, to showcase their talent in film and photography. However, times change and, as the global community wakes up to the reality of increased pressure on the world’s resources, exacerbated by the onslaught of climate change, there has been a change in artistic practice. Today’s forward-looking artists focus on the reuse and repurposing of items in their pieces. Naz often uses black oil, linen, coal, iron and metal in her artwork. These materials have been described, by Kurdistan ART, as ‘controversial’: they certainly evoke reminiscences of the Industrial Revolution. The mention of coal always makes me shudder as it awakens in me recollections of my own family narrative and heritage. I am a proud northerner whose families toiled above and below ground in the pits of Northumberland and Durham. Coal was the lifeblood of the region; it also shackled many of its residents to a life of penury and hard labour. Oil is Kurdistan’s coal, the source of much the upheaval inflicted on the area. For me, the use of black oil in her pieces enables Naz to explore her heritage. Indeed, by featuring industrial items, such as coal, oil and various metals, or things that are associated with war, such as bullets, in her artwork, Naz comments on themes such as political issues and trauma. Her 2013 work, The Memory of Coal, illustrates this. Coal is an ancient substance (100 million to 300 million years old), that was formed under heat and pressure. Is this a metaphor for Kurdistan – a nation with a long heritage that is being subjected to heat and pressure, hopefully to forge an internationally-recognised, independent country? What memories do Kurdish people pass to each subsequent generation?

Naz doesn’t just repurpose objects for her art and present them in the state she finds them, her process is alchemical. To create some of her pieces, she chemically alters her material, bringing it back to its original state or transforming it into something new; thus planting her own inimitable presence on the artwork. In 2018, in her “Pre-Identity” exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sulaymaniyah, she created a dynamic installation art piece. This work featured drops of water from a tank onto an iron surface and showed the oxidizing effect of water on the slab of iron. How do you interpret this natural process that Naz brings about through the combining of elements? On a micro-scale is she playing God or is she reminding her audience that humankind cannot control the elements?

Naz often uses rusted metal objects in her work. It is too simplistic to interpret Naz’s use of rusted metal as representing corrosion and decay. However, there is also a duality to her art and these pieces can also be understood as salvaging items that have been discarded and giving them new life, like a phoenix rising from the flames. In 2017, she displayed her work “Rust Process” within the remains of a collapsed house as part of the exhibition “Argue-Object” in Sulaymaniyah. The display featured a slab of rusted iron and a tower of bricks. For me, this points to the precariousness of life and human control, at any moment the bricks feel ready to tumble down, bringing chaos to uneasy order. In another mixed-material work, Naz attached wiry metal and a half open aluminium can to a square block of rusted iron. Has the wiry metal escaped from the half open can, bringing disorder or is the wiry metal being put back into the can to create order? This uncertainty is one that Naz must often consider, from her conflict-ridden childhood to life in present-day Kurdistan: can anyone truly control their destiny and does chaos ever have purpose?

London in the Swinging Sixties was the coolest place in the world. This cultural revolution was youth-led, ushered in by the Black Trinity. Growing up during, and in the aftermath of World War Two, they modernised and revitalised British society and culture, made it more equal and fair. I see a similar originality in the work of current young, female Kurdish artists, as exemplified by Naz Hakim: they are determined to rebel against and change the status quo. Wouldn’t it be great if Naz’s post-conflict art presaged an era of Kurdish cultural prominence and coolness?