4,441 Total views, 1 Views today

Author: Kiaksar Ahmed

Translator: Shadyar Shorsh

Babasha was a thin, Jewish man of average height, calm and quiet. The only notable thing about him was the color of his eyes, deep and grey-blue. He came from Iran, or rather the eastern part of Kurdistan, to the southern part of Kurdistan in order to sell tea.

He explored many cities and villages of different countries; he even visited and bought tea from some of the finest farms of China and India. Furthermore, he discovered the secret of white tea with an English trader named Charles Stow. Babasha tried to be like Charles Stowe; he tried to not let his emotions influence his trade and, because of that, he was one of the wealthiest tea traders.

One day, after selling a lot of tea in Sulaymaniyah, he put some jewelry and money into a pouch and placed it in his pocket. He intended to go back to Iran from Penjwen’s border town. But he didn’t know that it was Friday and that a mullah, in his Friday prayer, indicated that if someone killed a Jewish person, he would be rewarded with a large mansion next to that of the Prophet Mohammed. This is why Babasha was beheaded by some Muslim men near Kany Hayat, in the village of Barkew. They stole his money and jewelry too. Babasha left behind his wife, a six-year-old son and a girl. This all happened at a time when being Jewish was considered a sin and crime in life.

Many years after Babasha’s murder, when Shex Mahmood Hafid ·lost an unequal war against the British army near Kirkuk, two of his soldiers did not leave the battleground; they courageously fought the British army until they ran out bullets, after which they were arrested. One of the two soldiers was Babasha’s son.

“When we were arrested, Rashy and I, they approached us with fear because they thought the strips of wood we carried around our waists were bullets. They were unaware that if we had had just one more bullet, we would not have allowed them to get closer.” — This is a story within our family.

The British army would hand over the two soldiers to Iraq’s monarchy. They were kept for a while in one of the prisons in Kirkuk. They were denied a lawyer or trial and were condemned to be hanged. But because of the instability and turmoil at the time, their sentence was delayed. “After a few months, due to a letter from Shex Mahood Hafid, we were spared execution. I never touched a gun again, and I never saw Rashy again”.

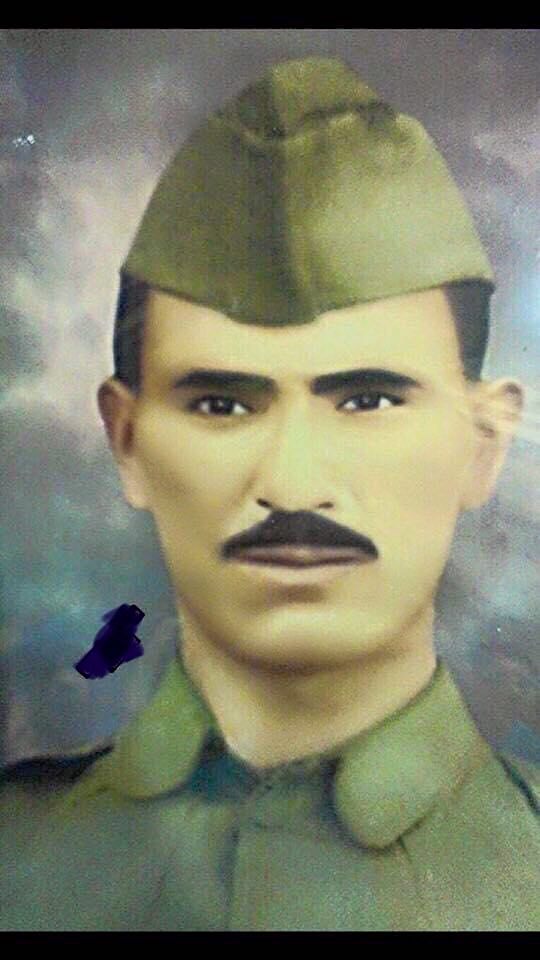

Later, Babasha’s son would return to the town of Penjwen. He was a lonely person, without relatives or support. There, in Penjwen, where everyone had a nickname, in no time they gave Babasha’s son one: Xwlla Hatew, meaning “orphan”. Hatew was a butcher, so he was also known as Haji Mahoody Qasab, meaning Mahmood the Butcher. He is my grandfather.

After a while, a man called Mulla Ismail would give his daughter Raana in marriage to Xwlla Hatew, and she would become my grandmother. The thin and feeble Xwla Hatew had many stories, a flighty nature with a body with no identity. He had a habit of watching the sunset in the evening with his blue eyes, placing his crooked fingers over his bushy eyebrows. Often, storms bent his body in his Kurdish clothes like bindweed. In the summer, he swam in the large creek, Chamy Gawra, and looked out at the sky as though he could see the Milky Way, wondering whether there were Jewish people like himself on other planets because he didn’t know any personally. When he came out of the creek, he stood until he was no longer wet, the cold breeze from the mountain chilling his skin.

He let people see his body, then he exposed it to the wind. He closed his eyes and tried to quiet his thoughts, falling into a deep meditation. The wind made waves on his loose skin and tired body. He spread his curved arms and fell in love with the strange fantasies he imagined, with a slow and silent dance.

Xwla Hatew’s arms were slim, but there was a remarkable power to them. The elderly people of Penjwen always told my grandpa’s stories and said, “We swear to God that Xwla Hatew could knock an ox to the ground all on his own.” With Mina Bchkoly Qasab, they took the herd of animals from Penjwen to Kirkuk — yes, all of it — just by walking.

He was an angry and restless man; he had a strong conscience and spoke roughly. He is now buried in Pasha Mosque (Mezgawty Pasha) next to the great Mullah Malay Gawra. He never told us stories; maybe he hated stories. He got his grey-blue, glassy eyes from his father and his lisp from his mother. He was a Jewish man who lived for 97 years, and every day he ate four to five lemons. He never compromised his principles for anything or anyone. He was born Jewish, but he died a Muslim.

- Sheikh Mahmud Barzanjior Mahmud Hafid (1878 – October 9, 1956) was the leader of a series of Kurdish uprisings against the British Mandate of Iraq.