3,434 Total views, 1 Views today

by Sarah Mills

It is with a macabre surrealism that Kurdish artist Jwamer Dishad depicts his women. Contemplating the feminine subjects of his artwork, the viewer is inevitably led to recall the twofold struggle for independence that Kurdish women face – freedom from both foreign occupation and from a perniciously patriarchal society.

In times of war, the distinction between genders undergoes paradoxical shifts. The gap closes as women are thrust into conflict alongside men and demonstrate their formidable, and equal, capacity to defend and to fight. This gap also, however, tragically widens as the horrors of war expose the vulnerability of women to the sexual violence that inevitably accompanies it. In this way, Dishad’s art has a universal element to it, one that transcends nations.

Although the theme of war cannot be entirely extricated from Kurdish contemporary art, Dishad’s works are not confined to it. His female portraits also reflect a fight that unites women across borders and regardless of geopolitical states of affairs – the fight against male dominance.

The pain of objectification and sexism is pervasive in Dishad’s portraits. His women are dehumanised, dissociated, disjointed creatures whose eyes, either absent or distant, almost never hold the viewer’s gaze, but whose breasts often do. The sexual is the defining feature upon which identification of these women as, in fact, women hinges. We see them through a very specific lens – the male gaze.

Breasts, whether maternal or sexualised, depending on the viewer’s perspective, are more often than not the focal point, the immediate resting point of the eye in many of the portraits, an effect that is achieved through colour, highlighting, and placement. It almost seems at times that Dishad’s paintings are a study of breasts, much like a still life of a bowl of fruits might be in another case.

The face is often obscured, the body grotesque, distorted, and animal-like in Picassoesque fashion. Colours are neutral and intense at turns, depending on whether the portrait is a sketch or an oil painting. Broad strokes in the latter impose an aggressive feel that can seem violent or threatening. What is certain is that Dishad does not shy away from the morbid implications of misogyny.

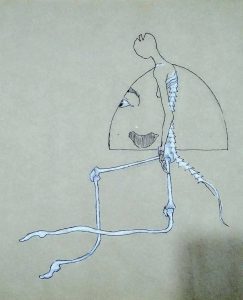

As with many of Dishad’s pieces, it is the breast that labels the subject female. It seems an imposition. There is nothing about this creature that would otherwise designate it so. It is hardly human. Anthropomorphic, yes, but also alien-like or even biomechanical, with a long tail and a digitigrade walk. An eye and an eyebrow seem to denote that the semicircle beside the figure is a face. It trails alongside the faceless, slumped-shouldered creature, separate and forward-looking. The viewer cannot help but notice the creature’s open head and, in true Picassoesque fashion, is left wondering whether the protrusion might not be, in fact, a tongue, indicating that the head is in an entirely different position than originally imagined. It could also be a sort of locking mechanism, by which the creature’s face was once attached to its head. We cannot know, and this may very well be the artist’s intention. The creature is jarring in the uncertainty it confers to the viewer. But we do know this – it is visibly skeletal, light (in terms of weight), and seemingly suspended, floating. When you tilt the sketch ever so slightly to the left, it almost resembles a jellyfish or a kite, endowing the portrait with a whole new perspective. The distinct impression is that of emptiness, illness (conferred by the pallor of the palette), unbearable weightlessness, and forced concealment. Perhaps a commentary on the othering of woman? Or on the compulsion to present herself one way when she feels another? Or, more likely yet, on the dismissal of the contents of her mind? All three, and undoubtedly more.

If the figure of the previous sketch seemed kite-like by virtue of its dimensions and impression of weightlessness, this one seems an even more plausible case for a similar interpretation. The figure to the right of the woman (again, only so as a consequence of her breasts) is not immediately discernable as a man, but, as with Dishad’s other drawings, the onus is upon the viewer to disengage the mind from more conventional representations in order to reassemble this puzzle into comprehension. The woman floats above the man, who stands with his feet firmly planted in the ground and his head bowed. He grasps her limp, malleable hand with excessive force, but she only looks bewildered, curious, or perhaps jaded, resigned. She is also beside him, in a purely two-dimensional way. The light hits the sketch in a strange, unnatural manner. It touches the man’s head, her shoulders (barely), her compliant hand, her breasts, and her forehead. Much like the previous figure, she is thin and airy. The man is solid and grounded, his fist curled into his side, as in protest. Is he the shackle on her aspirations? Does his fear compel him to hold on too tightly so as to not lose her? She unsuccessfully tries to cover her chest with one arm. It seems she would rather not be here, but somewhere off in the distance, wherever her gaze lands.

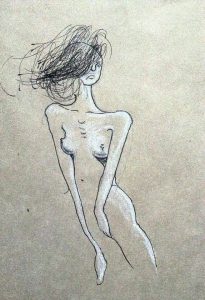

Similarly to the first two sketches, there is a transparency achieved by a consistency in colour between the background and the figures themselves. The black outlines lift the subjects from an otherwise pale or neutral background. Our third figure is clearly emaciated and angry. Her wispy hair appears to drift from her scalp like the pappus of a dying dandelion. She covers her intimate parts. She gives me the impression that she would also like to cover her chest, annoyed with her exposure. Is she shocked at what she is seeing? She seems more a participant than a spectator, as though something has just happened to her. The passive voice is fitting here, as she does not appear to have acted but to have been acted upon. And yet, she does not cower in shame or retreat. She holds her head high in the face of the wind and gazes with disappointment and resentment at whatever or whoever has just provoked her.

Dishad makes more use of colours in his oil on canvas paintings than in his sketches. The same blue shade is present in this and the following image. Here, the artist includes his characteristic depiction of breasts, but they are not the focal point. Rather, they appear to either side of the woman – in the top right corner and on the left, just across from her hip. They are scattered like subliminal messages, perhaps in the same way two pairs of buttocks can be seen on the right. There seem to be other women besides the central one in the painting. We see the figure from a different perspective this time. She is exposed, as usual, but we cannot discern her facial expression, which offers her some protection. She faces a black object – a tree? What appears to be liquid falls from the top of the painting down her hair, arms, and upper back. Is she showering? Is it raining? Whatever the liquid is, it appears dark and viscous and sullying. In the bottom right corner is a black mass. It could be the hair of another woman, suspended or reclining somewhere beyond the confines of the painting. The disembodied parts lend themselves to an impersonal gaze; without a face, the body parts are just that – body parts, void of spirit and character.

Here again is the same cold blue as in the previous oil painting. Breasts are the focal point. Where the rest of the painting is either a blur or a series of broad brushstrokes, the chest is drawn with a strong attention to realism. The subject’s face fades, as a force similar to wind seems to pull it away. Her arms are (tied?) behind her back, but there is defiance in her disappearing features. She sits firmly against a noisy, tumultuous, chaotic background. This is a rare instance in which the subject appears to be actually looking back at the viewer.

There is a striking use of bold red here that distinguishes this painting from the others. The perplexing dualism also necessitates a more attentive reading. Much like in the previous painting, the artist employs heavy brushstrokes to create a background of tangled, overlapping ribbons that provide depth and give the impression of a forest. The woman (or, more appropriately, the disembodied head and chest) is either bleeding or has caused something else to bleed and become stained in the process.

Is she a victim of violence or a predator? What look to be raven’s feathers recall the traditional imagery of a harpy. The heavy-lidded eyes of the subject convey remorselessness if she is the perpetrator of violence and numbness if she is its victim. The sombre painting exudes death and callousness in the face of it.

In this especially cold painting, the chest once again is at the centre. The breasts are swollen, as might be the woman’s stomach. Is she pregnant? She is light against a tenebrous background, but her face is still obscured by her hair and by the shadows. The surface upon which she is seated seems unyielding; it must not be a bed. It is more reminiscent of a prison cell. She gives off a sheen, radiating her own heat, despite the cold air of the painting. She is heavy, in stark contrast to the emaciated figures of Dishad’s sketches. Is she meant to represent hope, maternity, new life against all the odds? We could attribute such a positive reading to this work. In a world that would engulf her in its darkness, she remains in the light. We could, however, likewise see this in a very different way. While that which makes her unique, her facial features, is hidden, her breasts are on full display. She is only a body, the sum of her secondary sex characteristics. Unsurprising in the context of a Kurdish woman’s struggle for freedom from the shackles to which her sex has been bound for centuries.